Arthur Fairbanks '86. Longmans, Green & Co., 1933.

Our Debt to Greece and Rome" is the underlying theme of a series of small volumes on different phases of the classic past. "Greek Art," the thirty-ninth and newest of the series, comes from the pen of Professor Arthur Fairbanks, who taught at Dartmouth both before and after his term as Director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The volume is dedicated "to my students in art at Dartmouth College, whose interest and cooperation gave form to this essay."

Probably no other aspect of classical civilization so well confirms and illustrates "our debt to Greece" as does the field of Greek art. For the Greeks developed the greater part of that aggregate of techniques, conventions, and principles of artistic expression which we call "the classical tradition." And this tradition has been the most important single influence upon the art of Europe and America.

Professor Fairbanks traces for us the growth and continuity of the tradition. He tells how Greek art was taken over by Rome and what Rome contributed to its resources. The resultant Graeco-Roman art survived the Dark Ages to instruct and inspire the earliest medieval builders. Largely lost and forgotten during the Gothic period, in the Renaissance antiquity was remembered and rediscovered. Collections of Greek and Roman objets d'art were made, ruins were studied, and the ever-increasing treasure of classical remains taught the Renaissance artist the vocabulary of ancient art. As the past became more clearly revealed and better understood, its influence on European art became more direct. The Neoclassic period of the early nineteenth century represents the logical conclusion of the Renaissance trend; Neoclassic architecture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries proves that Greek architecture is at last an open book, well understood in every detail—save perhaps its spirit. And many feel that this spirit, unfettered at last from the conventions which have clung to it, is to be found in the best art of our own day which is, surely, classical in feeling. (One might well argue that the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington is more truly Greek in spirit than the Nashville Parthenon or the Lincoln Memorial.)

Such was the course of the Greek tradition. Professor Fairbanks devotes another chapter to its content. He describes first the technical processes of coinage, metal work, sculpture, drawing, and so forth, which we inherit from the Greeks who first brought them to perfection. But "the message of Greek art to later generations is the message of the Greek people" and that message is not a question of details and techniques but of the aims which inspire art and the principles which control artistic expression. Unity, order, harmony, balance, a blend of realism with idealism, a seeking to express broad human values rather than limited individual ones,—these considerations are still paramount in art today.

This thesis—that Renaissance and modern art stand heavily in debt to the art of Greece—is, to students of the subject, a commonplace. One cannot help admiring the fresh enthusiasm and persuasive eloquence with which Professor Fairbanks retells the story. His inclusion of an illustrated summary of the main developments of Greek sculpture, his logical organization, and his clear and simple language make this useful little book a model of its kind. It should appeal to student and layman alike.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

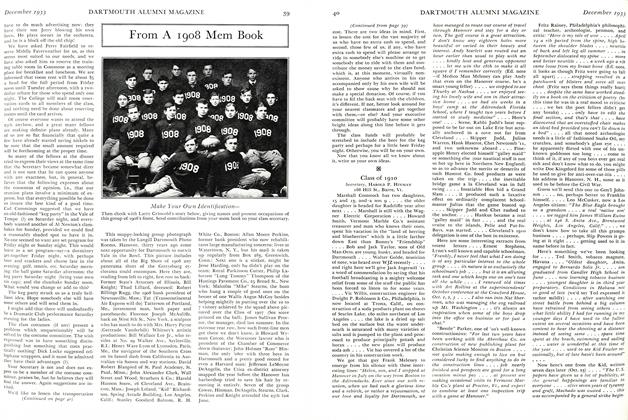

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING, A WAY OF LIFE

December 1933 By Arthur G. Tozzer '02

Hugh S. Morrison

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

MARCH 1929 -

Books

BooksA MIRROR FOR AMERICANS. LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE UNITED STATES 1790-1870 AS RECORDED BY AMERICAN TRAVELERS.

January 1953 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksTHAYER SCHOOL REPORT ALUMNI FUND, 1941

April 1942 By F. H. Munkelt '08 -

Books

BooksMARRIAGE.

April 1933 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksTHE INDIAN AND THE WHITE MAN.

NOVEMBER 1964 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25 -

Books

BooksRUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER SHINES AGAIN.

November 1954 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26