Authors of Modern Ski Technique"

WAXING SKIS is probably one of the most discussed phases of skiing. The scores of different waxes on the market combined with the fact that there are so many conditions of snow make the subject at first seem more bewildering than it really is.

That the subject is important has been repeatedly shown in racing where it has often been clearly demonstrated that a race was won more by superior skill (or luck) in the way the skis were waxed before the race. The fact that one man's skis are waxed so that he can easily climb when another man has to use a great deal of energy to prevent his skis from slipping back has often been the determining factor in a cross country race.

The purpose of waxing is three-fold. It prevents the snow from caking on the skis. It helps the skis to glide faster. It can prevent, or lessen, the slipping backward of the skis when climbing. Although skiing under many conditions may be done satisfactorily on a bare ski, most skiers find it more satisfactory to always use wax so that they never ski on bare wood, but always on wax.

Waterproofing the Skis

The first step in waxing skis is to thoroughly waterproof the wood. This is done with some sort of oil or tarry substance which penetrates the ski and tends to toughen and preserve the wood. Experiments conducted by manufacturers of wood products show that if wood is water-proofed so that no moisture can penetrate, the wood will not warp. Another reason for waterproofing skis is that waxes will not stick to wet wood. One of the most common and satisfactory methods of waterproofing skis is to apply raw linseed oil. The skis must be perfectly dry. When the first application of oil has penetrated the grain apply more oil, then repeat the process several times. A new pair of hickory skis will easily absorb a pint of raw linseed oil. When the applications of linseed oil have been completed the skis should dry thoroughly and then be rubbed smooth with steel wool or sand paper. Ski manufacturers endorse this process. Applying pine tar to the ski and "burning it in" with a blow torch is another excellent way of waterproofing the skis.

Skis can also be waterproofed by the Montan Process. The skiis are placed in forms so that they hold their shape. They are then immersed in a bath of hot oil and wax under high pressure for several hours. Probably this is the most satisfactory method, as it forces the oil and wax through the entire ski.

After the skis are waterproofed they are ready for the application of "base" wax, otherwise known as "foundation," or "ground" wax. There are different varieties of base wax on the market. Many of them are a sticky, tarry substance. These are sometimes applied with the aid of a blow torch or a hot iron. Another satisfactory way of applying these waxes is to dissolve them in some solvent such as Carbona and then paint the dissolved wax onto the skis. This method is not practical on the trail, but is a convenient way to apply wax at home. The solvent evaporates quickly and also helps the wax penetrate the wood. Several coats may be applied if desired. The ground wax, which is a foundation for the surface or running wax, should be allowed to dry and harden before applying the surface wax.

Waxing Combines Luck and Skill

Successful waxing can not be done by any rule of thumb. It depends on so many conditions of temperature and texture of the snow, which are never exactly duplicated, that a skier is forced always to use his judgment. Ability to predict the weather is an important item. Luck will most always play a large part. We recall a down-mountain race where a competitor had but one kind of wax with him. No one thought this was the right kind of wax for the existing conditions. No one else was using this wax that day. There was nothing else available for this fellow, so he used it. But with this wax he made the best time of all, although he was not as good a skier as many other competitors. We mention this to show that luck plays its part even among experienced skiers.

Although no rule of thumb can take the place of a man's judgment, there are some general principles and: suggestions which may be useful to a skier while he is acquiring experience on which to base his judgment.

First of all do not expect the impossible, perfection. Even if a man could predict the weather and snow conditions perfectly he could not twice apply wax in exactly the same manner. If a skier does not expect perfection he will not become as disgusted as many do when waxes do not work as desired.

Copyright 1933 by Otto Schniebs and John W. McCrillis. From book "Modern Ski Technique" by same authors.

Some skiers make their own wax. Some of the common ingredients are paraffin, beeswax, beef fat, melted rubber, salt, and pine tar. However, there are so many excellent brands of wax on the market that most skiers find it more economical, infinitely easier, and generally more satisfactory to use wax which can be purchased at sporting goods stores. There are many varieties of several brands on the market today. New varieties are being constantly introduced from Europe, and domestic manufacturers are developing further kinds. Most waxes are now put up in containers bearing directions printed in English.

Simplifying the Problem

Waxes may be roughly classified in accordance with their hardness. They run from the hard paraffin base to the soft and sticky pine tar varieties. Most commercial waxes are between these two extremes, and we may roughly classify them as hard, medium, and soft. The hardest waxes are chiefly for gliding, or increasing the speed downhill. The soft waxes are for climbing. Medium waxes are used for both up and down hill. Some of the medium ones are called "universal" waxes, although it is a question whether any waxes have been made yet which can thus be correctly classified. There are some exceptions to the above, and it should be remembered that a given wax gets softer as the temperature rises.

Skis should always be dry before applying wax. Hard wax or paraffin should be applied to the groove. This will never bother. But if soft wax is applied to the groove dry soft snow may sometimes stick in the groove. The climbing properties of waxes are increased as the wax is applied thicker. The most satisfactory way of applying wax thick is to build it up in layers. When wax is built up in layers each layer should be allowed to dry and harden before the next layer is applied. Each layer should be rubbed smooth. The palm of the hand is probably the best thing with which to rub the wax, although a piece of cork is excellent. The wax should be rubbed from the front toward the rear of the ski. Wax is sometimes built up to the thickness of a dime. For jumping or down-hill running wax is usually applied thin. Paraffin is often rubbed over the wax for jumping. Usually the softer the wax the greater the help in climbing. However, if too soft wax is used in dry powder snow, the snow will stick to the skis badly. Soft climbing wax is good in wet snow. In coarse wet snow such as spring "corn snow" soft sticky tar-like wax is excellent for climbing.

Experienced skiers often use combinations of surface wax. For example, if the first part of a cross country race is to be uphill and a latter part downhill they will first apply a hard fast wax to the ski. Over this they will apply a softer wax which will aid in the climbing during the first part of the race. They will apply no more of this climbing wax than they think will wear off by the time the downhill part of the race is reached. In this way they will have the aid of the climbing wax during the first part of the race and the gliding wax during the latter part of the race. Sometimes hard gliding wax is applied to most of the ski, and the climbing wax is applied to that part of the ski under the foot. Some waxes will be found to stick to the ski longer than others. The durability of a wax should be considered, especially for racing.

Essentials for a Trip

With so many good kinds of wax on the market it is a puzzle to know what kinds to take on a trip. We have seen the man with no wax; also the fellow who has twelve kinds of wax in his pack together with a blow torch with which to apply it. But we think most skiers will do well to take a course between these two extremes and take about three kinds of wax—hard, medium, and soft—and then perhaps a cake of paraffin. If a skier sticks to these he will know how they work under different conditions and will usually have better results than he will if he tries a new kind of wax every day. We have no particular brief for any make of wax. Our suggestion is to go to a reliable dealer in ski equipment and get about three grades of wax and become familiar with the use of these before trying too many others.

A simple test which some skiers use in soft dry snow to see whether the ski is properly waxed is as wax is too hard. Then again put the ski in the snow, and after sliding it along pick it up and see if there is snow on the bottom. If there is, the ski is "too slow" that is, the wax is too soft.

A hot iron or blow torch is frequently used to assist in applying wax. If some kinds of wax are heated the properties of the wax change. Therefore, care should be taken not to apply too much heat to certain waxes. Generally speaking, soft sticky base waxes will stand the heat of a blow torch, but surface waxes will not.

Another aid in applying wax is a patented iron called "Para" which burns a solid spirit fuel. This is a light compact device which can be easily carried in a pack.

To prevent snow and ice from freezing to the top and edges of the skis it is well to apply hard wax.

Wax may be removed from skis by many solvents, including turpentine, denatured alcohol, gasoline, and Carbona. Scraping wax from the skis with a knife is the usual method used on the trail.

That they may have data for use in basing future judgments, some skiers keep a record showing the date of ski trips, snow conditions, temperature, wax used, and the results. This has proved very useful.

Although good waxing is a great help to better skiing its importance should not be over-emphasized. We should not lose sight of the fact that good skiing under many conditions is possible with no waxing. Boys who never heard of the intricasies of ski wax have become excellent skiers. They have enjoyed their skiing in spite of the fact that they have never been initiated into the mysteries of the "wax hounds," some of whom spend so much time waxing and talking about wax that one wonders whether they may not have forgotten that this subject is but one step toward better skiing, rather than an objective in itself.

Proper Waxing Would Help Necessary to easy climbing is correct waxing of skis. Arduous side-stepping may be avoided.

Application of Wax Illustrated by Coach Schniebs follows: Place the ski in the snow. Then pick it straight up and see if snow sticks to the bottom of the ski. If it does not the ski is "too fast," that is, the

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeath

February 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleA PRACTICING LAWYER

February 1933 By George M. Morris 'II -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

February 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1926

February 1933 By J. Branton Wallace, Ritchie C. Smith -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1933 By Frederick William Andres, Mace Ingram, Bill Keyes

Article

-

Article

ArticlePALAEOPITUS DECIDED

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleDrama and Music Festival

March 1939 -

Article

ArticleSome Books for Alumni Readers

November 1961 -

Article

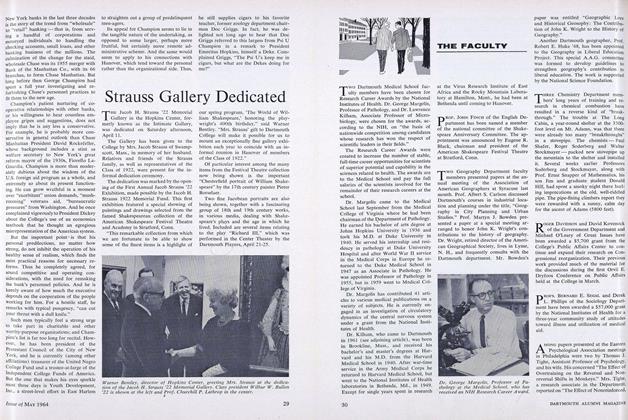

ArticleStrauss Gallery Dedicated

MAY 1964 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

April 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1953 By William P. Kimball '29