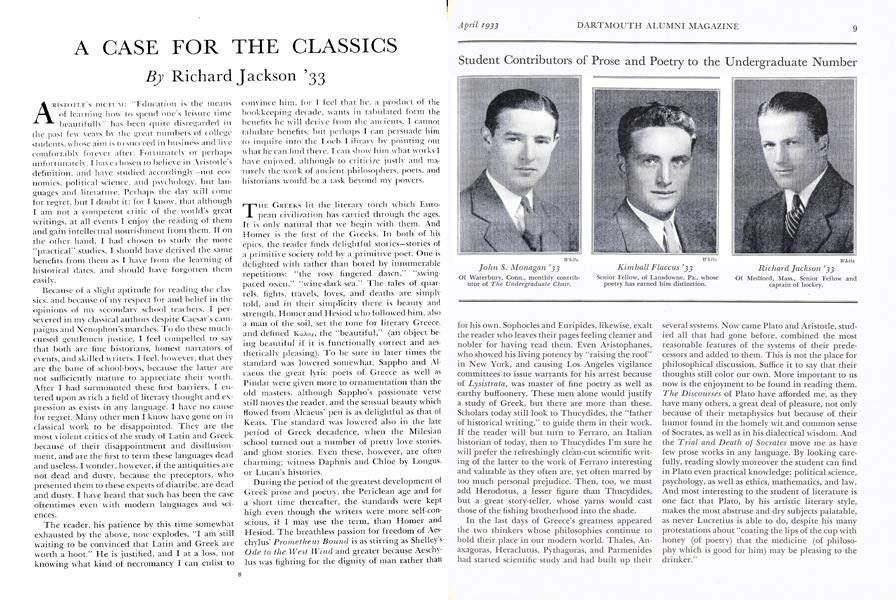

ARISTOTLE'S DICTUM: "Education is the means of learning how to spend one's leisure time - beautifully" has been quite disregarded in the past few years by the great numbers of college students, whose aim is to succeed in business and live comfortably forever after. Fortunately or perhaps unfortunately, I have chosen to believe in Aristotle's definition, and have studied accordingly—not economics, political science, and psychology, but languages and literature. Perhaps the day will come for regret, but I doubt it; for I know, that although I am not a competent critic of the world's great writings, at all events I enjoy the reading of them and gain intellectual nourishment from them. If on the other hand, I had chosen to study the more "practical" studies, I should have derived the same benefits from them as I have from the learning of historical dates, and should have forgotten them easily.

Because of a slight aptitude for reading the classics, and because of my respect for and belief in the opinions of my secondary school teachers, I persevered in my classical authors despite Caesar's campaigns and Xenophon's marches. To do these muchcursed gentlemen justice, I feel compelled to say that both are fine historians, honest narrators of events, and skilled writers. I feel, however, that they are the bane of school-boys, because the latter are not sufficiently mature to appreciate their worth. After I had surmounted these first barriers, I entered upon as rich a field of literary thought and expression as exists in any language. I have no cause for regret. Many other men I know have gone on in classical work to be disappointed. They are the most violent critics of the study of Latin and Greek because of their disappointment and disillusionment, and are the first to term these languages dead and useless. I wonder, however, if the antiquities are not dead and dusty, because the preceptors, who presented them to these experts of diatribe, are dead and dusty. I have heard that such has been the case oftentimes even with modern languages and sciences.

The reader, his patience by this time somewhat exhausted by the above, now explodes, "I am still waiting to be convinced that Latin and Greek are worth a hoot." He is justified, and I at a loss, not knowing what kind of necromancy I can enlist to convince him, for I feel that he, a product of the bookkeeping decade, wants in tabulated form the benefits he will derive from the ancients. I cannot tabulate benefits, but perhaps I can persuade him to inquire into the Loeb Library by pointing out what he can find there. I can show him what works I have enjoyed, although to criticize justly and maturely the work of ancient philosophers, poets, and historians would be a task beyond my powers.

THE GREEKS lit the literary torch which European civilization has carried through the ages. It is only natural that we begin with them. And Homer is the first of the Greeks. In both of his epics, the reader finds delightful stories—stories of a primitive society told by a primitive poet. One is delighted with rather than bored by innumerable repetitions: "the rosy fingered dawn," "swingpaced oxen," "wine-dark-sea." The tales of quarrels, fights, travels, loves, and deaths are simply told, and in their simplicity there is beauty and strength. Homer and Hesiod who followed him, also a man of the soil, set the tone for literary Greece, and defined ItaAos, the "beautiful," (an object being beautiful if it is functionally correct and aesthetically pleasing). To be sure in later times the standard was lowered somewhat. Sappho and Alcaeus the great lyric poets of Greece as well as Pindar were given more to ornamentation than the old masters, although Sappho's passionate verse still moves the reader, and the sensual beauty which flowed from Alcaeus' pen is as delightful as that of Keats. The standard was lowered also in the late period of Greek decadence, when the Milesian school turned out a number of pretty love stories, and ghost stories. Even these, however, are often charming; witness Daphnis and Chloe by Longus, or Lucan's histories.

During the period o£ the greatest development of Greek prose and poetry, the Periclean age and for a short time thereafter, the standards were kept high even though the writers were more self-conscious, if I may use the term, than Homer and Hesiod. The breathless passion for freedom of Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound is as stirring as Shelley's Ode to the West Wind and greater because Aeschylus was fighting for the dignity of man rather than for his own. Sophocles and Euripides, likewise, exalt the reader who leaves their pages feeling cleaner and nobler for having read them. Even Aristophanes, who showed his living potency by "raising the roof" in New York, and causing Los Angeles vigilance committees to issue warrants for his arrest because of Lysistrata, was master of fine poetry as well as earthy buffoonery. These men alone would justify a study of Greek, but there are more than these. Scholars today still look to Thucydides, the "father of historical writing," to guide them in their work. If the reader will but turn to Ferraro, an Italian historian of today, then to Thucydides I'm sure he will prefer the refreshingly clean-cut scientific writing of the latter to the work of Ferraro interesting and valuable as they often are, yet often marred by too much personal prejudice. Then, too, we must add Herodotus, a lesser figure than Thucydides, but a great story-teller, whose yarns would cast those of the fishing brotherhood into the shade.

In the last days of Greece's greatness appeared the two thinkers whose philosophies continue to hold their place in our modern world. Thales, Anaxagoras, Heraclutus, Pythagoras, and Parmenides had started scientific study and had built up their several systems. Now came Plato and Aristotle, studied all that had gone before, combined the most reasonable features of the systems of their predecessors and added to them. This is not the place for philosophical discussion. Suffice it to say that their thoughts still color our own. More important to us now is the enjoyment to be found in reading them. The Discourses of Plato have afforded me, as they have many others, a great deal of pleasure, not only because of their metaphysics but because of their humor found in the homely wit and common sense of Socrates, as well as in his dialectical wisdom. And the Trial and Death of Socrates move me as have few prose works in any language. By looking carefully, reading slowly moreover the student can find in Plato even practical knowledge: political science, psychology, as well as ethics, mathematics, and law. And most interesting to the student of literature is one fact that Plato, by his artistic literary style, makes the most abstruse and dry subjects palatable, as never Lucretius is able to do, despite his many protestations about "coating the lips of the cup with honey (of poetry) that the medicine (of philosophy which is good for him) may be pleasing to the drinker."

Now WE MUST turn to the Latins, disciples of Greece, never so great as their teachers, but interesting to us and valuable, because they are nearer to us chronologically, spiritually, and linguistically. The earlier writers of Latin are of scarcely any interest to anyone save the scholars, for they are, for the most part, slavish imitators of their Greek masters. We find in the two outstanding Roman dramatists however, Terrence and Plautus, the first glimmer of originality and interest. To be sure both followed Greeks models, but they at least were close enough to Italian soil to give their works an Italian flavor. Terrence is the nobler of the two and better dramatist, but Plautus has the larger audience because of his Rabelaisian humor.

Near the beginning of the Christian era we find Roman Letters at their best. Cicero set the rhetorical standard for generations after him, and established a slightly more florid school of oratory than Demosthenes, his austere Athenian teacher. More than this, he tried to vie with the Greek philosophers in his voluminous writings, the while practicing law in the Roman courts and violently playing the game of politics. In his writings he does not measure up to Plato and Aristotle, but many of his essays, such as De Senectute, De Amicitia, as well as letters and oratory, are worth reading even now, although his greatest wave of popularity ebbed when Burke, Fox, Webster, and Clay left the stage of politics. Far more of interest to us are the poets of that period, although Vergil and Horace are well known they would bear re-reading by most of us, for all three have a facility in the writing of smooth and beautiful poetry which charms the dullest ear. Lesser known are the so-called elegaic poets: Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius, who although lesser craftsmen than their better known confreres, are sincere and sound poets. No one of them attempted anything like Vergil's epic or Ovid's Metamorphoses, or Horace's epigrams, but none the less in their lyrical verse they seem to me far more honest than the above three, especially Ovid and Horace.

Soon after these men passed from the scene of Roman life, there was a lull in literary production and achievement until there arose, about Nero's time, such men as Tacitus, Pliny, Martial, Juvenal, Seneca, and Suetonius. Seneca would not please us much today, but the rest are very interesting. Suetonius, the journalistic historian and Walter Winchell of his day, tells us "all the inside dope" about the emperors whom he knew. Pliny, on the other hand, a gentleman and statesman, writes a great deal in his letters concerning the genteel Roman life of that period. Juvenal, a bitter satirist, gives us the opposite side of the picture in all its tawdriness. Tacitus, the greatest of the group, in his Annals and Histories;, tries to do justice to all sides. He is by far the most fascinating to read, for consciously or unconsciously, he has a sense of the dramatic, and his magical style changes history from a dull narration of events to a rushing, dynamic story, as gripping as a movie thriller. At this time, also, wrote Petronius, Nero's "arbiter elegentiae," whose Satyricon, well known to most people, needs no recommendation from me.

PERHAPS THE reader asks why it is necessary to waste time studying to learn the native tongues of my authors. My reply is that I feel one cannot "get" his authors undiluted unless he studies the original language in which they wrote. Ovid's stories are still charming in translation but they are not Ovid. The smooth, sonorous, rhythmic verse of Ovid is lost. Vergil and Homer and the dramatists suffer likewise. Prose authors are not as badly mauled as the poets in translation, but much of their charm is lost, none the less. Plato, using the elastic Greek as no prose author before or since has done, is a pure joy to one who likes to see a master craftsman employ his tools. Cicero is at his best in Latin as is the laconic Tacitus. The difference between the original classical language and the translation is much the same as the difference between an original oil painting and a photostat copy, or between a symphony orchestra heard in a music hall and that orchestra heard on a phonograph record. Some of us can't buy the original oils, or attend the symphony concerts; therefore we turn to photostats and records for inspiration. It is an unfortunate circumstance, however, when those who have the aptitude for learning to appreciate fine arts and the means to enjoy them, ignore music and the galleries—and the ancients.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN AVIATION

April 1933 By Carroll A. Boynton '33 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleNorthern April PART ONE

April 1933 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

April 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1933 By J. S. Monacan'33.