I REMEMBER reading not long ago in a chatty English periodical an article on Dr. Orchard—the well-known London preacher. The writer quoted a characterization of his preaching by a woman admirer who was overheard saying to a friend: "I do love Dr. Orchard. He thunders so magnificently and so beautifully." I am remined also of a similar statement in Wolfe's LookHomeward, Angel, in which he says of old Gant—the leading male character of the novel—that "he thundered magnificently and eloquently." These descriptions are relevant to the writers I shall discuss in this and the next issue. These are Sinclair Lewis, H. G. Wells, D. H. Lawrence, and Aldous Huxley. In various ways these also have the power and the will to "thunder magnificently and eloquently and now and then even beautifully." In a real sense the four are "sons of thunder." Occasionally they write as if they would like to call down on human society lightning and thunder from heaven.

At the same time there are significant differences between intuitive interpreters of experience like D. H. Lawrence, and a pitilessly sharp and clever commentator on the sophisticated stupidities of men and women like Aldous Huxley. Equally important are the differences between an acute critic of the contemporary world and its cluttering futilities like H. G. Wells and a sensitive and effective interpreter of the American scene and character like Sinclair Lewis.

I was made aware of these differences of style and motivation as well as ideals and social philosophy in reading their most recent works. I had not thought in advance of reading them together, but through the accidents of the distribution of new books it happened that their latest creative products reached me at about the same time. So I read them consecutively. Of course, poor, sad and tragic Lawrence, with his scratchy chest and feverish blood and restless brain, is now resting tranquilly in the spacious bosom of Mother Earth. Let us hope that at last he has found peace. The remaining three are intensely and vociferously alive. They still thunder in their respective styles. For there are different styles of thundering. One has only to read these men to be convinced of that. The books by them which I read for this issue are the following:

1. The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: Edited and with an Introduction by Aldous Huxley. The Viking Press. 1932. $5.00. This is a revealing collection of the amazingly honest and naked letters of Lawrence to his friends from 1912 to the year of his death in 1930. One of the most interesting books I have read for months, and worth careful reading by anyone desirous of knowing Lawrence.

2. Texts and Pretexts: An anthology with Commentaries. By Aldous Huxley. Harper and Brothers. 1933. $2.50. An excellent anthology with fascinating running comments on all sorts of subjects, by an informed student with a distinctive taste of his own. Those who want to understand Huxley will find this book really indispensable.

3. The Bulpington of Blup: H. G. Wells. The Macniillan Co. 1933. $2.50.

4. Ann Vickers: Sinclair Lewis. Doubleday Doran & Co. 1933. $2.50.

HAVING TASTED and enjoyed the letters of Lawrence I went on to read a number of recent books written around and about him. The best of these were:

1. Son of Woman: J. Middleton Murry. This is a Freudian interpretation of the life and work of Lawrence. Convincing only in certain parts—but mechanical and irrelevant and barren in other parts. Roots after all do not tell us much of any great value about fruit and its,quality.

2. A Savage Pilgrimage: Mrs. Catherine Corswell.

Interesting! in some ways but of limited appeal.

3. Lorenzo in Taos: Mrs. Mabel Dodge Luhan.

This throws light on Lawrence's pilgrimage to Taos. It contains also some interesting letters of Lawrence to Mrs. Luhan. These are not in the collection edited by Huxley.

4. I also read The Lovely Lady and other short stories of Lawrence published after his death. These have no real merit. His obsession with sex as expressed in these stories make them rather monotonous and difficult to read. His letters are much more interesting than his stories.

In connection with the highly individual anthology of Aldous Huxley I can commend very highly these two anthologies:

1. The Oxford Book of Sixteenth CenturyVerse: By E. K. Chambers. Oxford University Press.

a. Lovely Daughter: An Anthology of Seventeenth Century Love Lyrics. Edited by Earl E. Fiske. Publisher, Knopf.

Inasmuch as Huxley draws heavily on the poets of the seventeenth century I can recommend this collection of comic, gay, and amorous verses. Even Huxley could find in this volume many more rich specimens of the kind he likes.

As the best part of Sinclair Lewis' AnnVickers is woven around her experiences in prison work and administration, I feel certain that the following recent books on some phase or other of that problem will be found worth studying:

1. Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing: Lewis E. Lawes. Ray Long and Richard Smith. 1933. $3.00. A capital book.

2. Crime and Criminals: W. A. White, M.D. Farrar and Rinehart. Worth reading.

3. Probation and Criminal Justice: Edited by Sheldon Glueck. Macmillan Co. 13-00.

The penological views of Ann Vickers are in line with the best thought and practice advocated by modern penologists and criminologists. The achievements of women in social work can be studied best in books dealing with leading social and settlement workers like Jane Addams and Lillian Wald. And interesting biographies of able women somewhat suggestive of Ann Vickers are the following:

1. The Passionate Pilgrim: Gertrude Williams. This is the story of that remarkable English-woman—Mrs. Annie Besant with her strange mixture of intelligence and intuitive insight and gullibility.

2. My Thirty Years' Warfare: Margaret Anderson.

3. Living My Life: A remarkable two- volume autobiography by Emma Goldman.

BUT TO RETURN to my four "sons of thunder." All the four have some common elements, despite the more obvious affinities of Lawrence and Huxley on the one hand and Wells and Lewis on the other hand. In a general way they are all critics of contemporary civilization. Lawrence is regarded by some as a sort of prophet with a unique and individual message of regeneration, and some view even Wells as a prophet—a prophet of the coming world government. But I think a vigorous analysis of the ideas of both will reveal them as being more significant as critics than as prophets. And there is hardly any room for doubt as to the status of Lewis. He is primarily a timely critic of American institutions and ideas and ways of living. He cannot be placed in the ranks of the literary prophets, even though we may praise him as highly as Carl Van Doren does in his recent sketchy biography of Lewis. He states confidently that "Lewis will outlast John Galsworthy." I am not so certain of this. In any case the proper comparison should be Lewis and Wells and not Lewis and Galsworthy. And even here I would have a few doubts. He is a better and a more vivid story-teller than Wells, but he lacks the enormous range and the bold imaginative fecundity and the versatile achievements of Wells. Even as a social critic Wells is better equipped for his task, and his critical volumes have more real substance. Yet Lewis has opulent gifts of effective mimicry -which are lacking in Wells. He also possesses a genuine gift for powerful and memorable characterization. After all his Babbitt will live. So will Arrowsmith. The rest are more doubtful. He has contributed living words and vital types to our literature. Ponderevo in TonoBungay can hardly be compared with Babbitt. And Wells has not given us a convincing full length character like Arrowsmith. His William Clissold is not limned so satisfyingly. There is a raw vigor and a rough force and an exuberant gusto and a sharp sting to the best satire of Lewis not often found in Wells. On the other hand, Lewis lacks sympathy and pity and irony and subtlety. They seem to be beyond him. But that is almost as true of Wells. Both lack beauty and the highest imaginative qualities. Both also lack poetry and the subtler emotional qualities. The social philosophy of Wells has more body to it and seems to be better grounded than the somewhat vague humanitarian radicalism of Lewis.

I am aware that I am making generalized comparisons between the two writers but their most recent novels suggested them. In my opinion neither Ann Vickers nor the Bulpington of Blup is really success and first-rate. Both are too digressive and scattered in their characterizations. Both fall short of excellence. Lewis succeeds in giving body to his central character a little better than Wells.

Yet the best work of Lewis is his description of prison conditions and his portrayal of some of the minor characters. And in the case of the Bulpington of Blup the last section of the novel is more readable than the somewhat slow-moving and dreary early sections. His satire in the latter part of the book is effective. The depiction of Captain Bulpington in his Devon cottage and the humorous account of the dinner he had with Miss Watkins and Felicia Keeble is Wells at his best. There is real humor here—better than anything in Ann Vickers. It may be that I am somewhat hard to please in my fictional tastes, but it is not for the reasons given by Lewis in his Stockholm address when he stated that "our American professors like their literature clear and cold and pure and very dead."

THAT IS ENOUGH about the two novels and their authors in general. To be more specific I think Ann Vickers is one of the major novels of Lewis, although not quite up to the level of Arrowsmith and Babbitt. It does contain, however, his first fully developed picture of a woman charac ter. His Carol and Leora and Fran were much more limited. Ann in herself is an interesting woman, and in the course of her life she grows and changes and matures and mellows. Her problem is essentially that of satisfying her social and intellectual needs in and through a career of social service, and at the same time give a healthy and civilized expression to her biological needs as a normal woman. She makes many mistakes and blunders through her life but in the end she secures "her man and her child," and also succeeds in liberating herself from the prison of ambition and the desire for praise and her own clamant self. Her feminism in the end becomes biological and intellectual and almost wholly human.

Candor compels me to say, however, that for some reason or other I failed to get more than moderately interested in her struggles and ways of solving her life problems. She has many limitations. Her inner life is somewhat thin and immature if not external. And in spite of her real growth she remains in some ways a little naive and adolescent. She is not quite as great a woman as Lewis tells us she is—not if we judge her by her ideas and behavior.

The Bulpington of Blup of Wells is also a character study, but a mixed and satirical one. Much of the force of the satire is directed against the romantic world of fruitless reverie and unscientific habits of thought of Theodore Bulpington of the seaport town of Blayport. In his fantasies he became to himself the Bulpington of Blup-a romantic figure of heroic proportions. As such he was in the habit of "always jumping away from things," as his protagonist Teddy Broxted—the man of science-phrased it. Bulpington of Blup therefore is a romantic dreamer, progressively living in a world of reverie and wishful thinking. More and more as his creator Wells views him "Instead of thinking mightily, he took the common line and imagined abundantly." He had not been educated to look facts in the face after the objective and fearless method of science. Wells gives us an interesting picture of his childhood home and training. Wimperdick the Catholic apologist in the early discus sions-suggests strongly G. K. Chesterton and his ideas. The section dealing with the adolescent dreams and conflicts and idealizations reveals a sympathetic understanding of the difficulties and psychological characteristics of that age period. His early erotic experiences with Rachel, the radical Jewess, are described sensitively. His idealized relations with the Delphic Sybil—his boyhood friend Margaret—are likewise well portrayed. His pre-war adventures in socialistic and artistic circles in London give Wells a chance to discuss a number of things dear to his own heart. And the Bulpington's discovery of the comforting world of values is a delicious bit of satire, and for the rest of his life he never lost the consolation which "values" gave to his distressed and throbbing mind. The Great War caught him unprepared. It also gave him an excellent chanCe to strengthen his system of compensatory idealizations, and consoling rationalizations. But he could not face the hard facts of actual warfare, and he soon became a victim of war neurosis. The end of the war found him an inveterate romanticist. The Bulpington of Blup habit of mind from now on was definitely in the ascendancy. Disgusted by the marriage of Margaret to his rival, and realizing that it was the spirit of science embodied in her and her brother and her family which had overwhelmed him, he left London for Paris. There he found a home among kindred romanticists and defeated artists. He became the editor of "the latest thing in reaction," a smart periodical called The Feet of the YoungMen—a caricature of the magazine "transition." After ten years of exile he returns to England and goes to a cottage in Devon. In my opinion this last section is the best in the book. Long-winded discussions give way to a gentle but exuberant satire. And despite the final triumph of reverie, he becomes an attractive figure. In the end he returns home to his cottage half-drunk and salutes in a soldierly manner the old clock on the landing. A likeable romanticist at last.

Many of the characteristic elements in the social philosophy of Wells crop out here and there in this recent novel as well as in all of his recent books. He is still the crusader for a World State, and'the enemy of nationalism and war—the firm believer in science and planfulness, and the hater of the waste and the disorder and the cluttering inanities of modern civilization. And his main hope still rests in education, but the right sort of education. He can still say as he said in a preface to one of the novels of Swinnerton: "In the books I have written, it is always about life altered I write, or about people developing schemes for altering life . . . my apparently most objective books are criticisms and incitements to change."

And in so far as one can discern he still thinks that we are "devils, devilish fools, rather. Cruel blockheads, apes, with science in their hands." I wonder what the technocrats would say to that.

THE OTHER TWO writers on my list are pears of a different color and flavor. D. H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley. That would make an interesting book. So as a matter of fact would H. G. Wells and Sinclair Lewis. And if somebody would throw them together in the way I am suggesting in this issue I think one would have at least a spicy, literary omelette.

For the remainder of the space available this month I can do no better than suggest some of the qualities common to the works and temperament of these four men. In a sense they are all rebels—all individualists of a sort. All of them challenge the illusions and decaying conventions which have come down to us from the past. They are all fearfully sincere, even if now and then they do seem to resort to levity. And all four of them possessed a high degree of moral and intellectual courage. They tried also each in his own way to be faithful to the vision of life as they saw it. That after all is high praise for an artist. In the main the best works of all four disclose a refreshing freedom from old stodgy traditions and cramping tyrannies of thought. We can at least admire their challenging and withering honesty in facing the issues of modern life. They have done it in a spirit of relentless frankness. They have never sought to escape responsibility by dishonest evasions or weakening flights into the compensatory world of pappy illusions. They have all tried to portray candidly the world as they have seen it and as they have discovered it to be in their own experiences. Part of their work has been in a nature of a crusade for integrity of thought and magnanimity of mind. In doing this they have sometimes laid themselves open to the danger of binding themselves to new conventions—conventions of unconventionality and illusions of scepticism. It was Thomas Huxley who said that "our troubles begin when we are free to do as we please." And in a sense that explains some of the difficulties of each or all of my four "sons of thunder." There is something to be said for the best of the sheltering conventions and the protecting traditions of the past. We may find that living as children of freedom may be too difficult for the majority of human beings. Be that as it may, the passionate questing of these four writers after new standards and new values more in harmony with the tremendous ly complex world of today is something which readers of their books cannot but admire.

My discussion of Lawrence and Aldous Huxley will be continued in next month's article.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN AVIATION

April 1933 By Carroll A. Boynton '33 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleNorthern April PART ONE

April 1933 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

April 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1933 By J. S. Monacan'33. -

Article

ArticleA CASE FOR THE CLASSICS

April 1933 By Richard J ackson '33

Rees Higgs Bowen

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

January 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen

Article

-

Article

ArticlePinball King

January 1941 -

Article

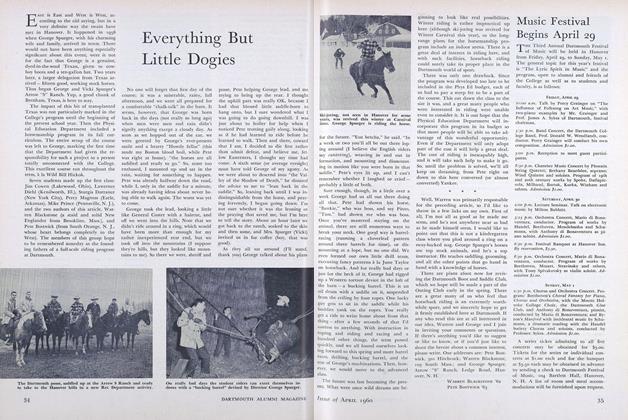

ArticleMusic Festival Begins April 29

April 1960 -

Article

ArticleThe Grand Old Class of ’66

OCTOBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleVisual Telegraphs

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleTOWN AND GOWN

DECEMBER 1962 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

Article1940

May 1951 By ELMER T. BROWNE, DONALD G. RAINIE, FREDERICK L. PORTER