ETUDE SUR L'OEUVRE DE SAINT JOHN DE CREVECOEUR, par Howard C. Rice '26. Paris, Campion, 1933. [224 pp. text, with bibliog., index and 7 plates.]

The straits of the farmer being what they are, it is pleasant to read in the writings of Saint John de Crevecoeur, that Franco-American "cultivator" of one hundred sixty years ago: * "I felt myself happy in my new situation, and where is that station which can confer a more substantial system of felicity than that of an American farmer, possessing freedom of action, freedom of thought, ruled by a mode of government which requires but little from us?"

Lest the reader be moved to answer ironically in terms of farm mortgages, income tax and the like, the reviewer hastens to say that this is a serious study of a phase of Franco-American relations—economic, social, intellectual. Written by a Dartmouth graduate of the class of 1926, in a French of remarkably good quality, it is a welcome addition to the growing number of such studies. The author was guided in his work by Professor C. Cestre of the Sorbonne. The publication has the imprimatur of the splendid Bibliotheque dela Revue de Litterature Comparee, directed by Professors Baldensperger and Hazard. These facts guarantee its scholarly sufficiency.

Crevecoeur long ago found his place, of course, in the history of American letters and life. Julia Post Mitchell wrote his life in 1916. Parrington, in his monumental The Colonial Mind, in 1927, devoted seven pages to him. There are many minor studies. Mr. Rice has improved upon anything yet done. He has utilized all preceding works of value. He gained access to letters still preserved by Crevecoeur's descendants. He put to good use the libraries of Harvard, New York and Paris. And very important, the European literary and social background is adequately contrasted with the American scene.

Michel-Guillaume Jean de Crevecoeur (1735-1813), a cultivated Norman gentleman, came to Canada at the age of twenty. He served under Montcalm at the capture of Quebec in 1759. After some time spent in Albany and Pennsylvania, he was naturalized an American citizen and settled down (1770-1775) on a farm not far from West Point. These years, the most happy of his life, he described in his Letters froman American Farmer and Sketches ofEighteenth Century America.

The American Revolution found him unprepared to take sides. Thrown into prison, he suffered in health, was finally released and returned to France in 1781. When he came back to the United States, his wife was dead, his children gone, his farmhouse burnt. For a time he acted as French consul at New York and interested himself in scientific farming and authorship. In 1790 he again returned to France where he died in 1813.

Since Mr. Rice's book is intended to be a chapter in the history of ideas, he wisely devoted relatively few pages to the life of Crevecoeur. This Franco-American, a contemporary of Franklin, Jefferson, Hamilton, Voltaire, Turgot, Rousseau and Condorcet, was a sharer in the humanitarian and economic ideas of his day. He was quite definitely of the Physiocratic school, like his fellow Franco-American, Dupont de Nemours, whom Mr. Rice fails to mention.

Had space permitted, it is probable that Mr. Rice would have developed more fully the doctrines of the Physiocrats and Crevecoeur's place as interpreter to America, in the sixth chapter of his book. As it is, Mr. Rice's work is a well-balanced and interesting study, that deserves a larger circle of American readers—in English.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1933 By Frederick William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

May 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

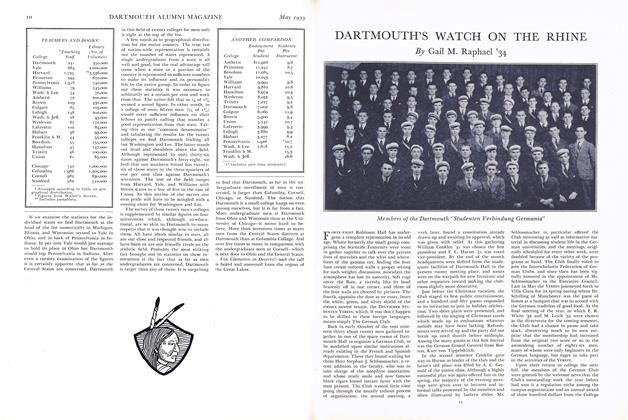

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S WATCH ON THE RHINE

May 1933 By Gail M. Raphael '34 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

May 1933 By Charles H. Owsley

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Land Was Theirs

September 1976 By Alexander G. Medlicott Jr. '50 -

Books

BooksTHE BOORN MYSTERY

November 1937 By H. H. Jackson -

Books

BooksSHOCK METAMORPHISM OF NATURAL MATERIALS.

APRIL 1969 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksPATTERNS IN THACKERAY'S FICTION.

APRIL 1970 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF BLINDNESS.

July 1956 By RALPH P. HOLBEN -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN NOVEL AND ITS TRADITION.

December 1957 By STEARNS MORSE