IN A WELL-KNOWN passage in DonQuixote, Sancho Panza defends himself by saying: "Why, truly, Sir, if you do not understand me, no wonder if my sentences be thought nonsense. But let that pass. I understand myself." I shall try to keep this in mind in what I intend saying about D. H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley. Especially desirable is it to do so with respect to Lawrence. He is the sort of writer that can be blamed or praised more easily than understood. I confess to a certain difficulty in understanding some of his ideas. And, as Sancho implies, what we do not understand, we tend to regard as nonsense. It may be, therefore, that some things in Lawrence I am tempted to call nonsense is just my inability to understand him. I assume that like Sancho he understood himself. The primary task of the artist is to understand himself. Whether he is understood by others is not his responsibility, provided he has done his best to make his work intelligible. This is by no means always the case as a lot of unintelligible modern literature testifies.

I hinted in last month's article that crit- ics differ violently among themselves as to the merits of Lawrence. Some denounce him severely as a sensual pagan. They say he is a specialist in sex and an exploiter of sex. Others say he is obsessed by sex. They explain him in terms of pathology or of Freudianism. They claim that he saw things out of their true focus. He saw sex in the biological sense in everything. His nature poems are charged with sex. As in his Birds,Beasts, and Flowers, his flower and plant and animal poems are saturated with sex imagery and symbolism. He is a sex and nature mystic at bottom. And it is this which accounts for his strangeness. The dark symbolism and curious morbidity of some of his books, particularly The Rain-bow and Lady Chatterley's Lover besides many of his shorter stories—are due mainly to his boldness in dealing with the problem of erotic human relationships. The occasional turgidity of his style and his awkwardness in telling a story are a part of the price he paid for his preoccupation with this problem.

To those who interpret Lawrence in this manner I recommend very strongly the reading o£ his Letters. I also recommend a collection of his poems entitled LastPoems—published by the Viking Press. This came to my hand since the last issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, and I enjoyed reading it so much that I read it twice. The unfinished poem in this volume called The Shipof Death I regard as about the best thing he did in poetry. All the poems on the death theme in the book are poignantly interesting. There are half a dozen other excellent poems in the collection. However, I do not rate his poetry in general as highly as his prose. His peculiar type of romantic sensualism and his dark and strange symbolism and the intellectual limitations of his ideas make his poetry too thin and flat and naively undisciplined. They lack artistic and intellectual substance. His best poems are good. Many of his inferior poems also contain noble and effective lines and images. But his very best poems are pregnant with a strange tenderness and instinct with a rare power and insight into the subtle rhythms of nature and of life. I realize the great unevenness of his workboth in prose and in poetry. At his worst he is stupid and pointless and boring. But that is true of a large number of poets and writers. Even the rifts of the best of them are not too loaded with ore.

I do not say that I agree with the severe critics of Lawrence. Neither do I go with his very enthusiastic disciples. For he has a goodly number of loyal followers. They tend to exalt him to the position of a significant prophet. They view him as a man with a living and a saving message for the modern industrial world. I am a neutral in this battle of the critics and the disciples. I like to read Lawrence but I cannot stand too much of him at any one time. And he has too many blind spots in his vision of life and in his understanding of our civilization to appeal to me as a prophet. There are whole provinces of life and thought outside the range of his mind—science, knowledge, philosophy, technology, industry, and many of our interests and institutions. But not much is gained by criticizing Lawrence for his failures and omissions. The business of the interpreter is with the quality of his work, with what he saw and felt and expressed and not with what he failed to see and feel and express. Let me say here that I think Lawrence was a genuine and original writer. There was nothing false about his work. There were no lies and no shams either in him or in his books. He was ever faithful to his vision of life. He never betrayed that vision even in his most debatable books.

Onre cannot do justice to Lawrence without realizing the fierce and challenging sincerity of the man. He at least, kept faith with his own spirit. Bitter he was at times. Now and then he broke out into a petulant irritability. Sometimes his words and moods were unworthy of him. Occasionally he was morbid, if not abnormal. Lady Chatterley's Lover may be interpreted as the last aggravating kick of a dying, disappointed man. In a sense it was that. Consumption was defeating him. The artist in him had been rebelling for many years against a civilization which he conceived to be "a shrieking failure." And in Lady Chatterley's Lover all of these things came to a focus. His painful chest, his irritation with the course civilization was taking, his growing restlessness, the loneliness and sadness of his life, and his sense of tragic defeat combined with his passionate faith in his own sexual philosophy came to a head in this book. A distorted novel—yes, —a terribly strange novel—but a failure.

Lawrence never can have a wide audience. It would be interesting to compare him with some other difficult modern novelists—like James Joyce or Proust. It would be helpful to assemble the respective statements of the faith and unbelief of some of these modern writers. Here, for instance, is one expression of the credo of Lawrence. It is taken from his peculiar book on Studies in Classic American Literature.

"That I am I.

That my soul is a dark forest. That my known self will never be more

than a little clearing in the forest.

That gods, strange gods, come forth into the clearing of my known self, and then go back.

That I must have the courage to let them come and go.

That I will never let mankind put anything over me, but that I will try to recognize and submit to the gods in me and the gods in other men and women."

That is rather a good statement of many of the recurrent ideas of Lawrence. Compare this with the sharper and more cerebral credo of another disturbing rebel—James Joyce.

"I will not serve that in which I nolonger believe, whether it call itself myhome, my fatherland, or my church, andI will try to express myself in some modeof life or art as freely as I can and aswholly as I can, using for my defence theonly arms I allow myself to use, silence,exile, and cunning." This comes from The Portrait of the Artist as a YoungMan. It reveals Joyce's loss of faith in his native land and culture as well as his breaking away from the religion of his youth.

But to return to the Letters of Lawrence. They show us a very sympathetic and courageous and likable personality. They are not letters to other people so much as a series of inner disclosures of the spirit of the man himself. This is a notable characteristic of all of the books of Lawrence. They constitute one immensely illuminating autobiography. He lived his writings, or rather his books were a part of his life. He conceived them in the anguish of his own fecund spirit. He nourished them in the protecting womb of his own wonderfully tender imagination. He brought them to birth through his own agonizing efforts, and he followed their fortunes with the deepest solicitude. They were in a real sense his children—flesh of his flesh and spirit of his spirit. And the Letters are a vital part of this process of self-revelation or self-reproduction. He was shedding his sicknesses in his books and letters as he stated it himself. He lives in them. His hopes and fears, his courage and cowardice, his loves and hatreds, his nobility and anger, his dreams and questings, his triumphs and defeats, his serenity and restlessness, his faith and unfaith, his wisdom and folly, his solitariness and sociability, his magnanimity and egoism, are stripped naked to our sight in his letters. They are not a collection of literary dead bones. The living breath of a rare and rich and poetic spirit is in them. The reader can see easily that they contain much more of wisdom than of knowledge. After all Lawrence was singularly deficient in knowledge but rich in wisdom, particularly where human relations and values were concerned.

His main interest was life in its flow and mystery. Not to know but to live life was his supreme concern. The highest art to him was the art of living. Life was the beginning and the end of everything. All things were made for life. Science, knowledge, industry, religion, art, all are ministers of life or else they are lifeless abstractions. His criticisms of industrialism, capitalism, democracy, socialism, bolshevism were made in the name and for the sake of life. His denunciation of science and formal education came out of the same concern with life. Science externalizes and intellectualizes life was the burden of his emotional critique. It elevates knowledge above life. It makes the devitalized abstractions of the intellect of greater significance than the intuitive, experiential knowing of the wonder of life directly through the processes of living itself. In this sense his antiintellectualism was more thoroughgoing than that of Bergson. It was not only an attempt to justify the intuitive way of knowing reality. It was deeper than that. It was the anti-intellectualism of life itself in its immediacy and variety and strange mystery. The intellect and its instruments —such as science and mediate knowledge —were attacked because they came between us and life. That at least was Lawrence's conviction, for it was a conviction and not a logic. Of course it may be held that Lawrence in trying to get back to the immediate flux of life was bound to be defeated and confused. The mistake he made was not in asserting the primacy of life but in denying the value of mediate knowledge. As is always the case in instances of this kind (the history of mysticism and naive realism is full of examples) it is what is denied and not what is affirmed that leads to obscurantism and muddleheadedness. And in the last analysis Lawrence was no exception.

IT WOULD BE gratuitous for me to defend science against his assaults, for the reason that they flowed out of his emotional convictions. He rejected the claims of science very largely on emotional grounds. And where emotions and convictions are concerned argument and logic are of little avail. And he rejected science not only intellectually but also emotionally. To accept science intellectually while rejecting it emotionally—a frequent compromise in these days—was impossible to Lawrence.

It is serious intellectual limitations of this nature that bar me from considering sympathetically claims made for him that he had a regenerative message for our age. He did not possess a consistent system of thought. Neither did he have any fruitful body of social thinking. Nor did he have a satisfactory philosophy of nature or of spirit or of knowledge or of religion or of values. And his understanding of social life was too limited. Many aspects of culture were not within his purview. His greatness depended not on his thought but on his sympathetic understanding of the subtle and intimate relations of men and women, and his insight into the polarized nature and mysterious rhythms of human emotions. He is astonishingly clear-sighted in this field. He had a penetrating knowledge of the anatomy and psychology of human emotions. Yet he failed to express this knowledge in systematic terms. His best attempt at doing this was in the Fantasia of theUnconscious. But the book is a failure.

But I would be doing Lawrence an injustice if I brushed aside as of no consequence his criticisms of modern civilization. Those who interpret him altogether as a sex-obsessed novelist do him much less than justice. For one thing he means much more by sex than is usually meant by the word. And as for thinking that he exploits sex in a pornographic way that is to miss his meaning almost completely. The sophisticated and semi-promiscuous sexual behavior found in some modern novels would send him into a passionate rage. And there are other things in his works besides sex. One has only to read the Letters to find that out. Let me quote just one letter in this connection. It was written in 1928 to Charles Wilson.

"It's a nice thing to make them live on charity and crumbs o£ cake, when what they want is manly independence. The whole scheme of things is unjust and rotten, and money is just a disease upon humanity. It's time there was an enormous revolution—not to install Soviets—but to give life itself a chance. What's the good of an industrial system piling up rubbish, while nobody lives. We want a revolution not in the name of money or work or any of that, but of life—and let money and work be as casual in human life as they are in a bird's life, damn it all. Oh, it's time the whole thing was changed absolutely. And the men will have to do it. You've got to smash money and this beastly possessive spirit. I get more revolutionary every minute, but for life's sake. The dead materialism of Marxian socialism and Soviets seems to me to be no better than what we've got. What we want is life and trust; men trusting men, and making living a free thing, not a thing to be earned. But if men trusted men, we could soon have a new world, and send this to the devil."

In between the lines of this letter one can detect what he wanted, and how his mind worked. His criticisms of science, education, religion, of our mechanical and competitive civilization and its ideals and purposes, of cities and money and machinery are presented often with acuteness. Space, however, does not allow me to elucidate this aspect of his teaching.

IN ALDOUS HUXLEY we have another writer having some elements in common with Lawrence. He also is an individualist in life and philosophy. He also is a rebel against many of the dominant ideals of a machine civilization. Do we not find him saying in one of his early rebellious poems: "Blast the whole lot of you. I hate you all." And he has remained a rebel at the core of him—a diabolically clever one at that. Unlike Lawrence he has a certain artificial, if not perverted, cleverness. There is in him an urbanized sophistication, a pitiless intellectuality, and an enormous mass of erudition which were alien to Lawrence. He sometimes parades his modernity. That is his weakness, and sometimes his strength. The revolutionary individualism of Huxley is also much more egoistic and conscious and intellectual than is that of Lawrence. Reared in a classical home, with scientific traditions in the family, and a product of Eton and Balliol —it was well-nigh impossible for him to entertain Lawrence's ideas about science and education. Huxley is much more of the objective observer of life. He is a mercilessly sharp spectator and interpreter of certain types of modern men and women. He watches them keenly at close quarters. He unravels their mixed motivations, dissects their characters, unmasks their illusions, and reveals blindingly their shams and pretences and compensatory rationalizations and compulsive ideas and fantasies. This he does with the unconcern of a scientist in a laboratory. Yet throughout it all he is a sincere artist with a tremendous capacity for challenging levity.

There is no falsehood or dullness or incompetence about his work, although he is occasionally artificial and rebelliously adolescent. But he tells us no simpering lies about life. Nevertheless, he lacks the sympathy and tenderness of Lawernce. He is the ruthless analyst and not the poetic seer. I personally think that Huxley lacks some of the qualities of the highest type of creative writer. He fails often in effective characterization. Many of his characters are really types. And the types he understands and portrays the clearest are men and women of the sophisticated pseudo-intelligentsia. The frustrated artist, the emotionally deficient intellectual, the romantic voluptuary, the sentimental libertine, the introspective dreamer, the imaginative pursuer of erotic experiences, the connoisseur of emotional thrills, the collector of masculine and feminine conquests, the drawing-room and impotent flirt, the feminine grasshopper, the neurotic quester after compensatory illusions, the superannuated flapper of both sexes, the homo-sexual misfits, the peddlers of society gossip, and the endless talkers. The end of life in a Huxley novel is talk and loquacious dissipation. And of the two I think the garrulous men of his novels are more than a match for his strident ladies.

These are the types he likes to describe with fiendish delight. Their behavior and movements are depicted in such a pointed manner as to create something like disgust in the reader. The only way this can be avoided is to acquire the habit of looking at these people in the same way and spirit as Huxley himself. That is how I like to read a Huxley novel. As a result the emotion it engenders in me is almost a static emotion—the real esthetic emotion according to St. Thomas Aquinas. The novels which lend themselves to a treatment of this sort are Chrome Yellow,Antic Hay, Those Barren Leaves, BraveNew World, and some of his shorter stories which in general I dislike.

Point Counter Point demands closer attention. There are disturbing overtones and undertones in this novel. Some of the leading characters in it are caricatures of real people. Rampion and his wife are Lawrence and his wife. Burlap is to a certain extent J. Middleton Murry. His picture is generally unsympathetic if not cruel and unfair. The trouble is the reader does not know where fact ends and fiction begins. To present real people in disguised form in fiction is dangerous and almost inevitably is bound to be unfair. Despite this, Point Counter Point is a diabolically clever achievement. The same may be said of that fantastic Utopian satire—Brave New World. It is well worth reading. The first half is excellent satire. Present bio-chemical, and psychological, and technological possibilities and experimental trends are projected into the future and become delightful and surprising realities. The Central Hatcheries and the Conditioning Centers and the Bokanovsky process and the Professors of Emotional Engineering and the Greek lettered functional groups are described as effectively as his brother Julian—the biologist—describes love among the birds. The Brave New World is a biochemical and behavioristic and technological paradise, the makers thereof are Ford and Freud. It is a fantastic Utopia where civilization is sterilization, where cleanliness is next to fordliness, where everybody is happy, where no pains are spared to make lives emotionally easy, where Ford's in his flivver, and all's well with the world, where everyone belongs erotically to everyone else, where everybody is conditioned to like what they have to do, where unorthodoxy of behavior is the only sin, where home, father, mother have become obscene words, where the rulers have no use for beautiful old things and books, and where high art, and poignant poetry and difficult thought and dangerous freedom and tragic emotions and literature are sacrificed for stability and standardised happiness.

In the second half of the book is found what I term the most civilized "go to hell" in post-war literature. And that is saying a great deal, for modern ture is rather rich in this respect. This really civilized "go to hell" is uttered impeccably by John the Savage in response to the appeals of Marx. He tries to get John to open the door of his apartment so that Marx may exhibit him to the prurient crowd outside. Even a college teacher would have said "go to hell" in the same circumstances.

To those who know Huxley only through his novels and poetry let me recommend some of his general books. His philosophy and ideas are presented in a purer and more consistent form in these volumes. The best of them are the following: 1. Do As You Like.2. Essays New and Old.$. Jesting Pilate. 4. Proper Studies. 5. Texts and Pretexts.

One must read these interesting books if one is to know Huxley. The novels give an incomplete picture of him. In conclusion I would like to quote a passage by Chelifer in Those Barren Leaves. I venture to suggest that it expresses very pointedly some of the ideas of Huxley himself. "There is no room," says Chelifer, "to be particularly proud of qualities which we inherit from our animal forefathers and share with our household pets. The gratifying thing would be if we could find in contemporary society evidences of peculiarly human virtues—the conscious rational virtues that ought to belong by definition to a being calling himself Homo Sapiens. Open-mindedness, for example, absence of irrational prejudice, complete tolerance, and a steady reasonable pursuit of social goods. But these, alas, are precisely what we fail to discover. For to what, after all, are all this squalor, this confusion and ugliness due but to the lack of human virtues?"

Here I think speaks Huxley himself. It is his faith in these virtues which explains why, as he says, he goes on "piping up for reason and realism and a certain decency."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1933 By Frederick William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

May 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

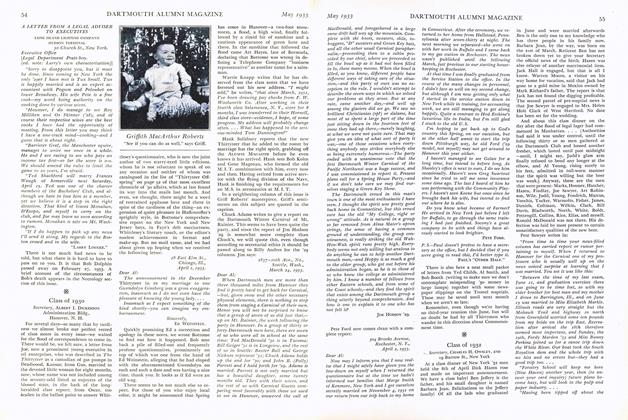

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S WATCH ON THE RHINE

May 1933 By Gail M. Raphael '34 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

May 1933 By Charles H. Owsley -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

May 1933 By Arthur E. Mcclary

Rees Higgs Bowen

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN FORM CLUB OF SEVEN IN BUENOS AIRES

January 1924 -

Article

ArticleReunions '91-'16

February 1941 -

Article

ArticleCorrection

SEPTEMBER 1987 -

Article

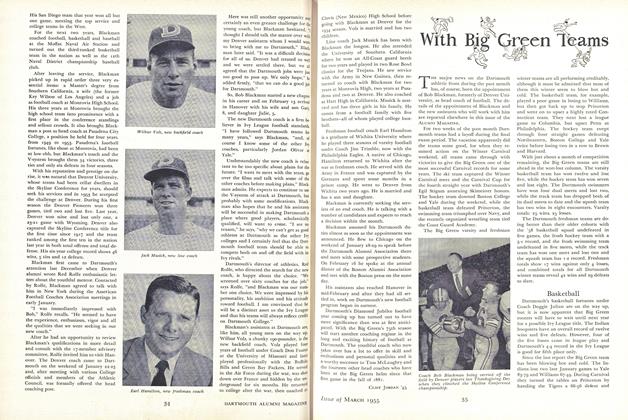

ArticleBasketball

March 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleHeritage Tourism

NOVEMBER 1999 By Jack DeGange -

Article

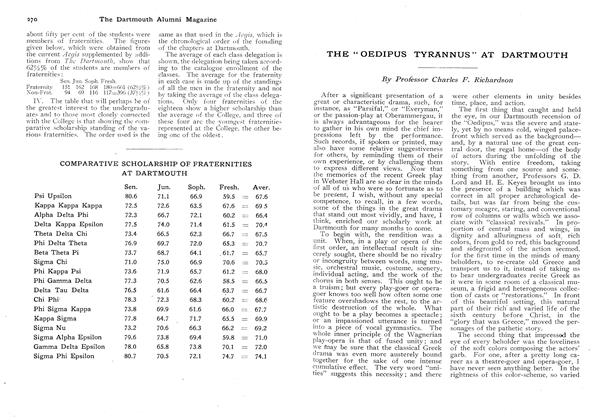

ArticleTHE “OEDIPUS TYRANNUS" AT DARTMOUTH

May, 1910 By Professor Charles F. Richardson