FOR THOSE of my readers who are attracted to medicine as a vocation, I would earnestly recommend that before their final decision is made, they read diligently such outstanding works on the subject as are contained in the writings of Sir William Osier (Councils and Ideals) the most gifted of modern physicians; and those of J. M. T. Finney (The Physician) one of the foremost exponents of surgery, The Medical Career by Harvey Cushing, The Training and Rewards of the Physician by Richard Cabot, The Young Man in Medicine by Llewelyn Barker, Medicine as a Profession by Daniel W. Weaver. These at least and probably many others may be read with profit, before the young man or the young woman finally turns to medicine as their chosen work in life. These writers have given, in such a delightful way, comprehensive and vivid pictures of what it means to be a true physician, that it seems presumptious to attempt, in a few paragraphs, to paint even an outline of the greatest of all vocations—the practice of medicine.

One tiny word describes the foundation upon which success in the practice of medicine inevitably rests—work. So unalterably true is this fact that the great physician Osier has written an immortal monograph with this as its title. Not only those of you who are inclined toward medicine but every student at the outset of life should read this monograph until it is indelibly graven upon his memory, for it applies to every human being who achieves success.

The inescapably necessary incentive for the student of medicine is the absorbing desire to be of service—service to one's fellow men. Unless this desire is a controlling, directing and active force in the heart and mind of the student he will do well to choose some other avenue through which to exert his energies. Without this basic desire he who enters the practice of medicine will find it a dreary existence. Coupled with a desire for service to humanity must be a natural inquisitive and acquisitive tendency—l use the word acquisitive as applied not to material things but to knowledge. These two mental tendencies must be inherent in order to be of sufficient urge for the development of a useful and successful career. Medicine, the practice of medicine, is an absorbingly alluring occupation, but a steady daily grind with no letup from the beginning of student days all through the years until the shadow of old age shall have fallen upon him. To the student, and I use the word student advisedly, for the physician never passes out of the realm of that category, there is no more exciting career than the practice of medicine, exciting beyond any of the experiences of a Jesse James or an A 1 Capone. To the right minded physician who knows not what tomorrow holds for him, each new day is filled with incidents which test his capabilities, excite his enthusiasms and stimulate anew his desire to delve into unknown paths of investigation. This illustrates my meaning in saying that one of the prerequisites for success in the practice of medicine is an inquisitive turn of mind. And by so much is the practice of medicine dull, dreary, and uninteresting, to the man lacking these qualifications for this vocation.

For him who has as the actuating motive of life monetary reward alone, medicine has nothing to offer. A few, a very few, physicians have acquired substantial fortunes from the practice of medicine, but what is not generally recognized is the fact that the monetary rewards have been merely incidental to, or the result of, high development in the basic talents of which I have spoken. These men did not start out with the ambition to acquire great wealth, but with a determination to achieve the highest skill and to render the greatest possible service to their fellow men. Only a small percentage, a very small percentage, of the members of the medical profession are endowed with these two somewhat opposing capabilities.

in the field, of medicine'there are quite definite lines of endeavor calling for skilled workers of different mental trends, each as useful, and in each of which are equal opportunities for beneficent service to mankind. A small percentage have a natural gift or aptitude for scientific research, which requires a supremely active investigative turn of mind coupled with a prodigious capacity for concentrated work, as well as a sound training in the basic sciences. Such a man rarely ever achieves success in the clinical field in medicine. A larger pro- portion of workers in the broad field o£ medicine are fitted for the practice of one or other of the specialties. By far the vast majority of medical graduates find their best endeavors in bed side practice. The opportunity for service and for recognition of service is equal in each field. As Dr. Harvey Cushing has so aptly expressed it, "In these days when science is clearly in the saddle, and when our knowledge of disease is consequently advancing at a breathless pace, we are apt to forget that not all can ride and that he also serves who waits and who applies what the horseman discovers."

The preparation for the study of medicine is important. Medical educators, from a vast experience extending over many decades, have come to realize that a broad collegiate training is the wisest preparation for undertaking the study of medicine. One medical school, perhaps one of the outstanding medical schools on the North American Continent, requires not only a collegiate degree, but in addition, compels the student to take one year in study of the basic sciences before beginning the four years of intensive medical study, and a final year in internship, during which a certain portion of the time must be devoted to continuous study in the medical school, in order to win the coveted degree of Doctor of, Medicine. I am of the opinion that this course of procedure will come to be followed by many of the outstanding medical schools of the world. I say this notwithstanding the recent agitation in some quarters for a shortened period of medical training, a trend which many right minded medical faculties are strenuously combatting.

The foregoing is an adequate answer to the constantly repeated query as to whether medicine offers a good field of endeavor for college men. Another question in the minds of parents and students is whether the financial reward for the practice of medicine is sufficiently alluring. It is a question, a practical question, which is not in harmony with the ideals of the practice of medicine. To the right minded this question is so unimportant as to be negligible. It may be answered by saying that every competently equipped medical man, if he is of sound moral character, diligent and of reasonably sound health, can be assured of a good living and an enviable position in the community.

Your editor has propounded this question "Does the idealistic side of medicine wear off—if the glamour disappears what takes its place." My answer to this is that in the life work of the true physician the "idealistic" side of medicine grows para passu as the years wear on. To all others dreary, deadly boredom and grind takes its place. Such a one finds himself "in the wrong pew."

Another question propounded—"ls medicine becoming more scientific." To this I unhesitatingly answer yes. And because this is so, the practice of medicine calls for men of the intellectual type endowed with the attributes which I have already pointed out.

"What do doctors read—do they study—how do they spend their leisure." Doctors read constantly and everlastingly, day by day the outstanding medical journals—that is the sine qua non for keeping up with medical progress, and he who does not do this, in the years to come, will surely fall by the wayside. In addition to their constant study of medical literature they should and many of them do, constantly delve into literary works on a diversity of subjects. There is ever an increasing demand for a cultural background for the physician of the present day. The question of how they spend their leisure is one which cannot be answered in a sentence, nor do I think it calls for discussion other than to say that the successful physician spends his leisure in activities which keep him fit for the arduous life. So too do the eminently successful physicians develop hobbies outside of their profession. The theme which the great Doctor Wier Mitchell chose for his address before one of the graduating classes of the University of Pennsylvania was "The Medical Man and His Hobbies." In that address Doctor Mitchell stressed the vital necessity for every professional man to develop someone hobby outside of his daily routine in order to give him relief from his accustomed train of thought which is so necessary for one who is deeply absorbed in his life work. It makes little difference whether the hobby be something which takes him into the great open spaces, or which is concerned with the collection and knowledge of etchings. The great thing is to have such a hobby and to devote one's best energies to it. I agree with Doctor Mitchell that this is a vital habit which is too often overlooked and neglected by present day physicians. And the final question propounded to me is "What are the great difficulties of medicine—what are the great rewards." My answer to the first part of that question is, there are no "great difficulties" for those who have a real aptitude for this greatest of all professions. As I have said the sine qua non is work—work. To the last part of the question, the greatest of all rewards is the conviction that one has rendered to his fellow men service commensurate with the gifts with which the Great God has endowed him.

In closing this brief survey of the practice of medicine as a vocation permit me to say in all sincerity that I sympathize keenly with all men whose lot has not fallen in the practice of medicine.

M.D., F.A.C.P., Sc.D., L.L.D. Past-President, American Medical Association; Dean and Professor ofGastro-enterology, Georgetown University School of Medicine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

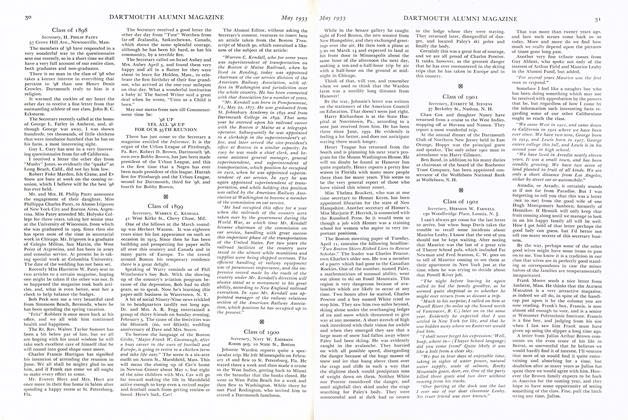

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1933 By Frederick William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

May 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

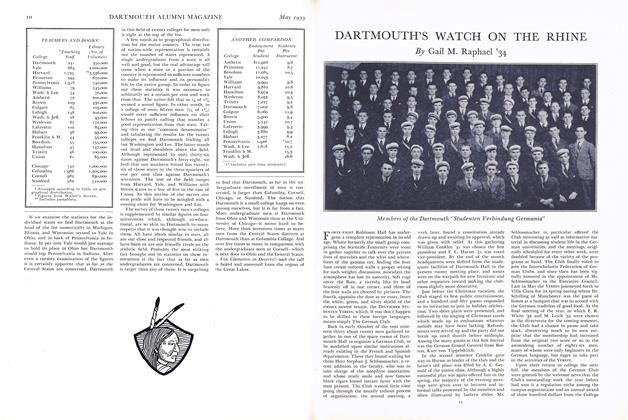

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S WATCH ON THE RHINE

May 1933 By Gail M. Raphael '34 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

May 1933 By Charles H. Owsley

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL HOSPITALITY LIKED

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Article

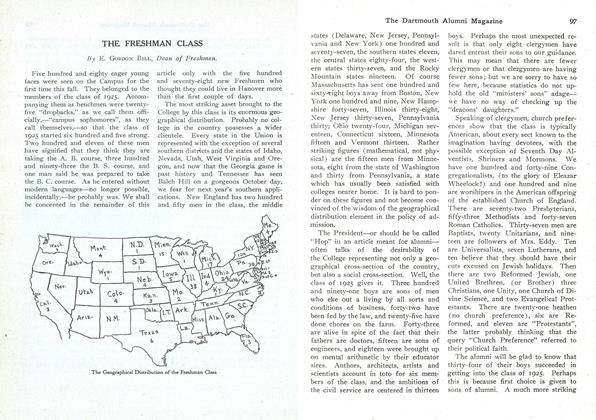

ArticleTHE FRESHMAN CLASS

December 1921 By E. GOKDON BILL -

Article

ArticleThe Imagination Unbound

APRIL 1992 By Ulrike Rainer -

Article

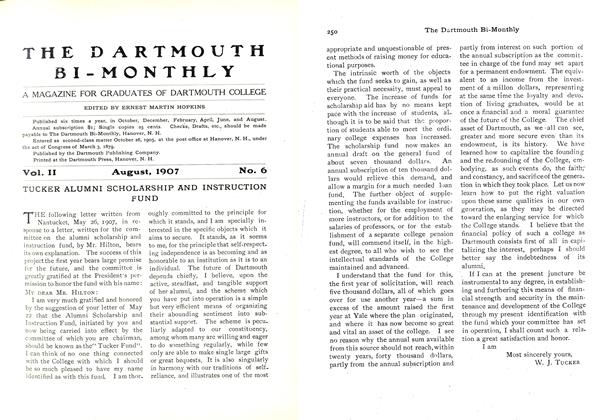

ArticleTUCKER ALUMNI SCHOLARSHIP AND INSTRUCTION FUND

AUGUST, 1907 By W. J. TUCKER