By Herbert Adolphus Miller '99, New York, Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1933.

The chastened mood of the present moment should afford an auspicious occasion for such considerations as Professor Miller urges in "The Beginnings of Tomorrow"; for he asks the reader to turn aside from the appreciation of his own civilization and bestow proper attention upon the portents arising in the Eastwhich in his use of the term stretches for 6000 miles from the eastern borders of Poland to the ends of Siberia, China and India. There great national destinies are working themselves out; there one-half of the earth's population is groping its way into a social order in which the immemorial traditions of the East are fused with revolutionary innovations from the West. That we ourselves have invested heavily in these transformations adds greatly to the interest for the western reader.

In Russia, for example, we see at the present moment, the vastest borrowing of foreign culture elements which has ever taken place at one time in the history of mankind. As Miller says, "To use a favorite European word, ideologies not of Russian origin had made ready for most of the revolutionary program." And not theories only but techniques of many kinds were available in the western world for appropriation by the helmsmen of the Russian adventure. Even religious iconoclasm, now carried farther in Russia than elsewhere, had its foreshadowings in our own Paine and Ingersoll. The emancipation of women and the reorganization of the family is to a degree the projection of a long series of contributions in which Americans from Lucretia Mott to Ben Lindsey have played a part. The Soviet principle of functional rather than geographic representation is, says Miller, "a forthright experiment in the same direction toward which America has been unconsciously groping." (At least it is safe to say that the government at Washington during the emergency of the World War was set up at least as much in accordance with functional as with geographical principles.)

It is needless to expand upon the extent to which pedagogical methods, prison reforms, industrial and agricultural technique, transportation and hydraulic engineering, are being borrowed'by the Russians from American and West-European sources. Here then is one of the arenas in which the whole world is involved in a cosmic sociological experiment whose progress affects us and our own techniques just as truly as our own pioneering in decades past has provided a respectable part of the procedures now on trial in Muscovy.

But after all only one of Professor Miller's sixteen chapters is concerned with "The Challenge of Russia." Equally stimulating are his discussions of the cultural give-and-take involved in our relations with Asia in general and with Japan, China and India in particular.

This is distinctly not another "travel book"; it is a book of interpretations—a pointing out of the import of the vast changes which the world of our day is undergoing. It is a mural (even a panorama) not a miniature, which is here attempted. Most readers of course will meet with passages or points of view in regard to which they will make their own reservations. To the reviewer Professor Miller's capitalized and personified Cosmic Process and his "inevitable" Cosmic Good constitute considerable of an enigma.

The comprehensive plan and purpose of the work may sufficiently appear in words quoted from the concluding chapter: "In every field of social research, the time has come for extensive as well as intensive study,. .. we must look at society as a whole as well as in detail. The object of this book has been to throw the larger process into bold outline. . . . Men of the older generation see in terms of old criticisms start new categories. We already gories. . . . Those who follow by their very accept the necessity of "social planning" but we need to make it on a scale that far transcends the economic planning out of which we now hope for salvation. The larger planning will demand a knowledge of .. . the whole range of social and political possibilities. We can look forward with faith and not despair, for the human nature with which we have to deal is a constant and marvelously flexible. ... It is one human nature that has produced all the varied cultures we have been studying with the economic, religious, and political forms that seem so exclusive of one another. It has possibilities of adaptation and development beyond the reach of our present imagination."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1933 By Frederick William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

May 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

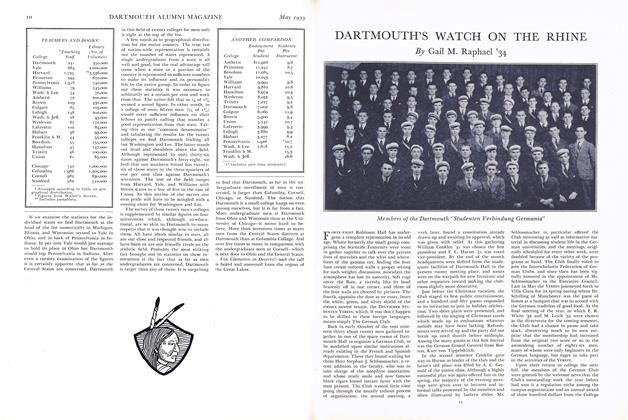

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S WATCH ON THE RHINE

May 1933 By Gail M. Raphael '34 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

May 1933 By Charles H. Owsley

Erville B. Woods

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April, 1915 By ERVILLE B. WOODS -

Books

BooksOld World Traits Transplanted

August 1921 By Erville B. Woods -

Books

BooksFarmers and Workers in American Politics

March 1925 By Erville B. Woods -

Books

Books"Old Dartmouth, an Appealing New Trend in College Room Decoration"

December, 1925 By Erville B. Woods -

Books

BooksMan and Society.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Erville B. Woods -

Books

BooksSOCIAL DISORGANIZATION

May 1941 By Erville B. Woods

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MARCH 1970 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2012 -

Books

BooksHUMANISM AND POLITICS. STUDIES IN THE RELATIONSHIP OF POWER AND VALUE IN THE WESTERN TRADITION.

JUNE 1969 By MAURICE MANDELBAUM '29 -

Books

BooksA STUDENT'S PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION

May 1935 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksNAW SU

April 1948 By VERNELLE W. DYER -

Books

BooksHOW TO RUN A WAR.

December 1936 By Wayne E. Stevens