From the Bethel (Vermont) Courier we learn of a talk given over Wellesley station WBSO on August 27 by Paul F. Wilson 'l4, long practically helpless from arthritis as a result of the World War.

GOOD AFTERNOON. Occasionally I am asked if life is worth living for me. I do not think it my place to decide this question. The Lord gave us life and He should say when it should be ended, and not us. I try to take things as they come and make the best of them. Before the war, I loved outdoor life. I liked to fish, hunt, play baseball, basketball and football. I danced late. I spent a hard season in the wheat fields of Saskatchewan, Canada. Possibly then I used up my reserve power. At least, during the war, my system could not stand the supreme test of the French mud. So you of the younger generation beware; do not overindulge in anything. You may think now that your store of energy has no end, but it has. If you abuse your health now, you will pay for it dearly later.

Two GOOD FINGERS

"In the years following the war, I gradually lost the use of more joints, and the pain was severe. Then it was hard for me to bear and harder for my wife and son. As the old saying goes. 'The first five years are the hardest.' It was difficult to give up the out-of-doors and be confined to four walls. But I stopped worrying about the future or the past and tried to live in the present. I fought my limitations. Every time I lost a new joint, I would improvise a gadget to make up the loss. For two years I had to be fed, until we bent a spoon to fit my two good fingers. My hips and knees have stiffened into a half-reclining position, making the ordinary wheel chair impossible for me. For four years we hunted unsuccessfully for a suitable wheel chair. Then we improvised one. The seat is tilted by an automobile jack so that the hips can be kept in a comfortable position. For my knees, we built a footboard extension, supported by leather straps. This could easily be done from any ordinary wheel chair or rolling chair. In this contraption, I attend baseball games, church, American Legion meetings, movies, and other gatherings.

"My two good fingers are weak, but we have built serviceable holders for reading books, magazines, papers, and even for writing. For five years I had no pencil in my hand. Now I can ivrite again fairly well. I wish I could pass along some of these ideas to some other bedridden patient, who can find no wheel chair to suit him. The average doctor has neither time nor patience to make experiments for individual needs. It is up to the patient or his best friend to overcome these physical handicaps. That means courage and hope. One must never give up fighting or lose faith.

"I know it looks peculiar to be pushed about town in a half-reclining position by a colored man. Many people, without thinking, gape at us. But why be self-conscious? It is only a form of selfishness. At first, it was hard for me to appear in public, pushed by a colored man, the wheel chair tipped back in a half-reclining position. But after a while I became used to being stared at. Then I realized that many people were looking at me out of kindness, instead of just plain curiosity. Too much sympathy is bad for invalids.

"There's another reason for my appearance in public. I think the general public should see some of the effects of the war firsthand. Too many living dead are hidden away in government hospitals. If all the cripples of the World war were in evidence, perhaps the youth of today might not be as eager to rush off to the next war. We were eager in 1917. Spurred on by false propaganda, we went overseas to make the world safe for democracy. Although we helped win the war, I doubt if the world is a much safer or better place. America has learned a bitter lesson. The World war was not our war. It was strictly a European war. This should be a good reason for us to keep out of foreign entanglements. Selfishly, I would like to see America keep out of war for twenty or thirty years at least. I would hate to see my thirteen-year old son turned into useless cannon fodder as millions of brave young men were in the war.

PLEASURE FROM RADIO

"So much for the war. The other day I heard Fred Hoey tell about Babe Ruth's home run. I can get a great kick listening to a good radio description of a baseball game, football game, or political convention. It is almost as good as actually seeing it. The radio is a great help to invalids, and the possibility of television gives us another reason to live. I wish all invalids could have radios beside their beds. I reach the radio dial with a pronged stick. I can turn it on any time, day or night, and thus I keep up with current events.

"The radio has great possibilities for good and bad. It can command some of the outstanding men of the country, recognized authorities in politics, religion, finance, or music. By a mere turn of the dial, on the other hand, you sink into the mire of a marathon, a walkathon, or a 'killerthon,' as I call them. This is what you hear: 'Come down to Revere and see the Golden Girl asleep on her feet. Look at her now. She's up! She's crawling on all fours! Come down and cheer her on!' This is pure foolishness, and what a waste of energy and health.

"Some people think that a government pension is like charity. I consider it pay for service rendered. The government took my legs away from me, so why should they not supply me with a helper? They have done everything possible for me, and I am satisfied with their treatment. For the past three years, Dr. Coleman of Wellesley has been giving me arthritic serum which we hope and think will save my few good-joints. I want to ask my many buddies in the hospitals, and anyone who thinks this is a hopeless world, to fight all the time. Never give up hope, for as soon as you give up hope, you are lost. Become interested in something to get your mind off your worries. Get a hobby if possible.

"In closing, I want to show that my life is not devoid of humor. Here is an example. All my travelling is done on a hospital cot in a baggage car. My wife, who has stuck with me through thick and thin, was riding in the passenger car. She passed the conductor the three tickets, saying, 'Two here, and my husband in the baggage car.' The conductor said, 'That's too bad. When did he die?' My wife retorted, 'Dead, nothing! He's the liveliest corpse you ever saw!'

"Good bye and good luck to you."

These are anxious days. Here is a message from one who has fought for sixteen years against physical handicaps. He is still fighting. Compare your condition with his. Paul Wilson of Wellesley graduated from Dartmouth in 1914. He volunteered in April, 1917, and was sent to France with the Seventy-Sixth Division. There he developed rheumatism, or arthritis as it is now called. After a year in government hospitals, he was discharged in June, 1919, with a bad back. It was a losing fight from then on, until three years ago. First the joints in his spine stiffened, then his shoulders and legs. First it was cane, then crutches, then invalid bed and wheel chair. Even a year's stay in Walter Reed hospital in Washington did not help much. All his joints have grown together now, except two fingers, both elbows, his jaws, and one wrist. He thinks the disease has run its course. At the age of forty years, he is sentenced to be confined to his bed or chair for life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePREREQUISITES OF INTELLIGENCE

October 1934 By Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1934 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1913

October 1934 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

October 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

October 1934 By Martin J. Swyer, Jr.

Article

-

Article

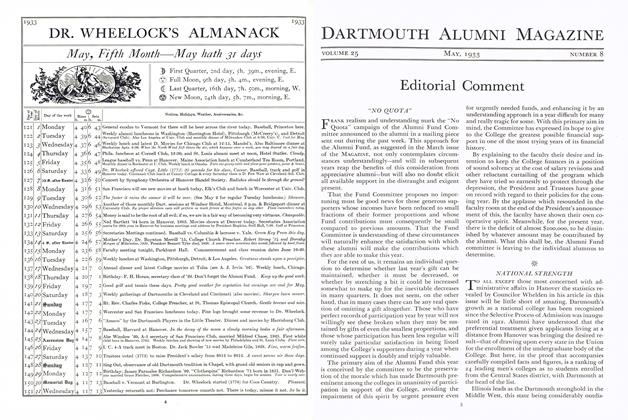

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S ALMANACK

May 1933 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

May 1962 -

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATE AFFAIRS

January 1915 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleA Poet in The Cosmos

NOVEMBER 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports Activities

January 1949 By John R. Zillmer '48 -

Article

ArticleThree Aleutian Love Poems

November 1946 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33