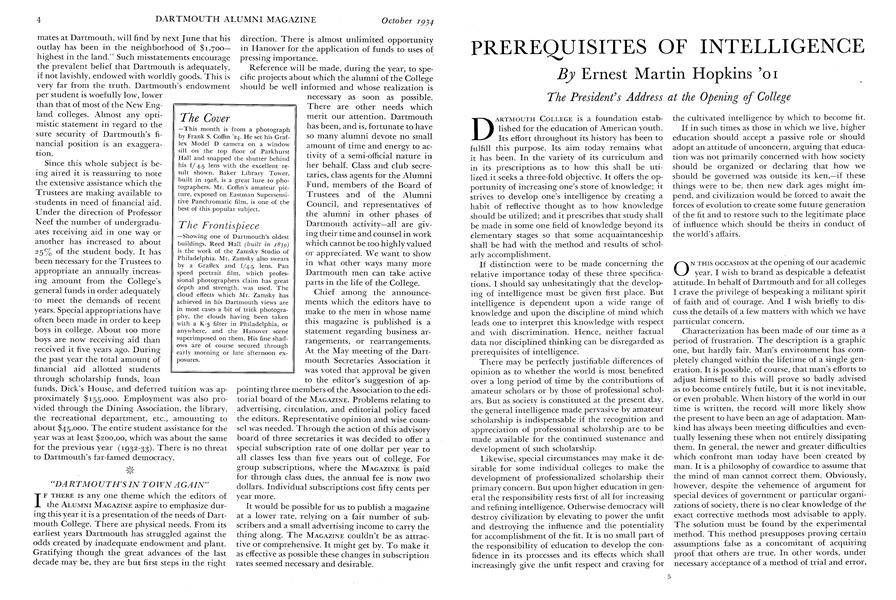

The President's Address at the Opening of College

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE is a foundation established for the education of American youth. Its effort throughout its history has been to fulfill this purpose. Its aim today remains what it has been. In the variety of its curriculum and in its prescriptions as to how this shall be utilized it seeks a three-fold objective. It offers the opportunity of increasing one's store of knowledge; it strives to develop one's intelligence by creating a habit of reflective thought as to how knowledge should be utilized; and it prescribes that study shall be made in someone field of knowledge beyond its elementary stages so that some acquaintanceship shall be had with the method and results of scholarly accomplishment.

If distinction were to be made concerning the relative importance today of these three specifications, I should say unhesitatingly that the developing of intelligence must be given first place. But intelligence is dependent upon a wide range of knowledge and upon the discipline of mind which leads one to interpret this knowledge with respect and with discrimination. Hence, neither factual data nor disciplined thinking can be disregarded as prerequisites of intelligence.

There may be perfectly justifiable differences of opinion as to whether the world is most benefited over a long period of time by the contributions of amateur scholars or by those of professional scholars. But as society is constituted at the present day, the general intelligence made pervasive by amateur scholarship is indispensable if the recognition and appreciation of professional scholarship are to be made available for the continued sustenance and development of such scholarship.

Likewise, special circumstances may make it desirable for some individual colleges to make the development of professionalized scholarship their primary concern. But upon higher education in general the responsibility rests first of all for increasing and refining intelligence. Otherwise democracy will destroy civilization by elevating to power the unfit and destroying the influence and the potentiality for accomplishment of the fit. It is no small part of the responsibility of education to develop the confidence in its processes and its effects which shall increasingly give the unfit respect and craving for the cultivated intelligence by which to become fit.

If in such times as those in which we live, higher education should accept a passive role or should adopt an attitude of unconcern, arguing that education was not primarily concerned with how society should be organized or declaring that how we should be governed was outside its ken,—if these things were to be, then new dark ages might impend, and civilization would be forced to await the forces of evolution to create some future generation of the fit and to restore such to the legitimate place of influence which should be theirs in conduct of the world's affairs.

ON THIS OCCASION at the opening of our academic year, I wish to brand as despicable a defeatist attitude. In behalf of Dartmouth and for all colleges I crave the privilege of bespeaking a militant spirit of faith and of courage. And I wish briefly to discuss the details of a few matters with which we have particular concern.

Characterization has been made of our time as a period of frustration. The description is a graphic one, but hardly fair. Man's environment has completely changed within the lifetime of a single generation. It is possible, of course, that man's efforts to adjust himself to this will prove so badly advised as to become entirely futile, but it is not inevitable, or even probable. When history of the world in our time is written, the record will more likely show the present to have been an age of adaptation. Mankind has always been meeting difficulties and eventually lessening these when not entirely dissipating them. In general, the newer and greater difficulties which confront man today have been created by man. It is a philosophy of cowardice to assume that the mind of man cannot correct them. Obviously, however, despite the vehemence of argument for special devices of government or particular organizations of society, there is no clear knowledge of the exact corrective methods most advisable to apply. The solution must be found by the experimental method. This method presupposes proving certain assumptions false as a concomitant of acquiring proof that others are true. In other words, under necessary acceptance of a method of trial and error. failure may be definitely a step towards success. A noted preacher once said that it was not to be assumed that God didn't answer prayer because he didn't always say "yes." By analogous reasoning, it is not to be assumed that an age is futile or that a generation is wasted because some of its major enterprises do not carry through to success.

On the other hand, under the experimental method it is imperative that projects be intelligently conceived, their development be painstakingly studied, the evidence adduced be critically scrutinized, and the eventual conclusions derived be accepted, regardless of doctrinaire opinion or preconceived ideas.. Herein I believe lies the greatest basis of doubt in regard to the immediate future in the affairs of government at home or abroad and in regard to desirable social adjustments throughout the world. The query constantly arises in the solicitous mind not so much as to whether the experiments being tried are likely or not likely to succeed, but whether they are being scrupulously examined and studied to learn what factors of promise or fallacy are contained within them. And it is only fair to add that valid judgments upon these seem more likely to be secured from the unbiased minds of men intelligently honest without brilliance than from the minds of men intellectually brilliant, but doctrinaire. Acceptance of this conviction in the conception of desirable educational programs might conceivably modify radically the theory and practice of institutions responsible for higher education.

THERE IS AN essay by Dr. F. C. S. Schiller on "Scientific Discovery and Logical Proof" which I wish every undergraduate might read. It is published in Studies in the History and Method ofScience by Charles Singer. In this there is one particular point that bears upon the matters we are considering; namely, the distinction between the prover and the explorer who may become the discoverer. Dr. Schiller argues that the mental attitude of the one must be quite different from that of the other, that the explorer seldom can be absolutely certain when he has become the discoverer and that verification lies with the prover. To be sure, Dr. Schiller assigns definitely lower rank of the two to the prover in the realm of research in the pure sciences, but from his comments on the inevitably great proportion of failures to successes among explorers, as compared with the provers, it is doubtful if he would make identical contentions in regard to the social sciences. Here inevitably the claims of discovery on the part of the explorers need to be checked by the provers at frequent stages. Unfortunately, the inhibitions of science, as demonstrated in medicine, against hazardous experimentation upon human beings have not become the ethical code of such wielders of vast political powers as a Stalin or a Hitler, for instance. Nor if the aspirations for human welfare of political leadership in America should fail, would we be free in the future from the probability of like experimentation upon ourselves. It is for such reasons that I believe it to be the duty of every real friend of governmental reform and of social advance to insist that provers be given equal place with the explorers in the great social and political experiments of the present day. Even if we accept as necessary a practice of experimentation under a theory of trial and error, provers might recognize error in its early stages and save much that would be lost, if mistake were carried to its final conclusion. As Seneca wrote, "An age builds up cities; an hour destroys them. In a moment the ashes are made, but a forest is a long time growing."

Theoretically, in a democracy the citizens possessed of the vote should be provers, weighing comparative merits and defects of governmental policies and rendering periodical intelligent decision as to the confidence to which these policies had proved themselves entitled. Practically, our political discussions in the past, as they will probably be in the immediate future, have been largely based upon our antagonisms and upon our dislike of specific details of policy, regardless of whether these were at all offset by other policies which in whole or in major part were defining progress or were conserving the national welfare. That this should be so is certainly an indictment of the influence of the educational establishment of a country wherein a quarter of our population, year by year, is enrolled within our schools and colleges, and wherein institutions of higher learning are given the opportunity of working their influence upon more than two million prospective citizens a decade. The responsibility, I believe, rests jointly upon certain attributes of the American college student body and certain defects in our official college conception of what are the real objectives of higher education.

I wish for a moment to leave general discussion and to be quite specific in regard to some aspects of our life together in this college.

In brief review of the history of higher education in the United States through recent decades, certain conclusions seem justified that bear upon the possibilities of common advantage in the relations that begin today between the institutional college and the undergraduates.

Important among these I should place the haziness of perception of the average undergraduate about the advantages available to him in a college course and his frequent lack of comprehension of the relative importance of these advantages, one to another. There is no truer saying than that the eagerly sought privileges of one generation tend to become assumed as rights in the next. Consciousness of values then begins to disappear. It is so of higher education in America today. Too large a percentage of the undergraduate bodies in colleges today are there because going to college is being done. Too small a proportion are there with any consciousness of the values obtainable or with any definite purpose to avail themselves of the particular benefits which will enrich their lives or make these of consequence to the greater welfare of mankind. The man who embarks upon his college course without either knowledge of where he is starting from or where he is going is subject to all the hazards of a mariner at sea without compass or chart.

It is in no censorious mood that I make these assertions, but rather in the hope that in recognition of the facts we may in some measure offset them. They result in some degree from the American aptitude for organization of worthy projects into systems of stereotyped forms, and in some degree from easy assumptions that blessings acquired by self-discipline and effort can be extended without impairment to those who have never labored or imposed any discipline upon themselves. Within the memory of a host of men now living there was no single institution of college grade in the United States that had an enrollment of a thousand students. Without question, even then in individual cases there was no full appreciation of what education was or why its influence was being sought. It would appear, however, from much of the data available in regard to the circumstances of college life of those times that the infrequency of opportunity to attend college, the literal fact that a college man was one in a thousand rather than one in a hundred, gave to individual students a sense of values in college opportunities which led to utilization of those opportunities which could be had to somewhat greater extent than is frequent in our own time. This statement holds in spite of the doubts of an occasional Henry Adams and in spite of the limited facilities of the institutions of higher learning of those days. It seems to be true that the more we have of a thing, the less consciousness we have of its worth, whether this be liberty, or health, or economic resources. So it is of educational opportunity. Even if, however, these things be necessarily true of students when entering college, there is no need that they continue true among those of a thoughtful group such as an undergraduate body may become.

I have read the editorial comment of undergraduate periodicals in recent years with considerable care. I have listened to extended criticism of college procedures and of college accomplishments in undergraduate groups at Dartmouth and at other colleges. In consideration of these with great interest and with some profit, I have nevertheless had much concern, as forecasting the temper of the great society which college men would later make up, that emphasis has been so largely placed upon what the colleges should do for their men and so little emphasis has been placed upon what these men should do for themselves. Much has been said about making the absorption of learning less difficult, the conditions of college life more comfortable, the procedures and programs more convenient, and the adverse judgments in regard to indolence and indifference less exacting. Little has been said about how learning should be made accurate, or about how mental fiber should be toughened, or about how intellectual fortitude should be developed.

IT is A SHORT step from such attitudes in regard to the relationship of a man to his college to the attitudes of the same man in his relation to government. And though the analogy is not complete, in the large it is true that as a government is what its citizens make it, so a college is what its undergraduates make it. A college may be made a pleasant refuge from ennui between week-ends, or it may be developed into a charming social center, or it may be utilized as an agency for sharpening the predatory instincts of its members and making these effective in relations in later life with their fellow men. On the other hand, a college may be made a sacred temple wherein one finds inspiration to seek truth, wherein are safeguarded treasures of the past whose values have been proved, and wherein one finds courage to abandon the easy assumption of things which are not so.

Quite incidentally also, I should like to refer to the frequent criticism, so vehemently made in the undergraduate press and recently repeated in popular magazines, in regard to the requirements in college curricula of disciplinary subjects requiring exact factual data, of some acquaintanceship with foreign languages, and of the ranking system. The hypothesis is usually accepted that except for conservatism and addiction to established forms on the part of the colleges, such requirements would speedily be abandoned. Well, they were abandoned in the most radically experimental project ever undertaken educationally upon a large scale when the Soviet Union set up its system of universal education and founded this on adoption of the project method. What was the result? In a resolution adopted by the Central Committee of the Communist Party on August 25, 1932, the whole plan was declared ineffective and undesirable in that it did not give sufficient general knowledge and failed to teach the essential basic principles of specific subjects. The resolution prescribed a more thorough study of individual subjects, more time to be spent on mathematics, physics, and foreign languages, and the reintroduction of examinations and the marking system. The recommendations of this resolution are now being put into effect.

Passing to broader discussion and to other than undergraduate obligations, we must admit the need that the college should accept greater responsibility for articulating itself to the rapidly changing conditions of modern life. We are so much involved in these and so much a part of them that except by definite effort we become insensitive to them. Factual knowledge and philosophical imagination are more indispensable than ever before, but these alone are not enough. The house of truth within which only the college has had justified residence must be expanded into a more ample abode of understanding. A man, for instance, may know all the obvious facts of an industrial dispute and yet have no understanding of it. To possess the latter he must have acquaintanceship with the history of the machine age, the principles of mass production, the theory of capitalism, the influences of the profit motive, the dislocations of labor resulting from wars and tariffs, the effects of monetary manipulation, the physiology as well as the psychology of fear, the incentives of ambition, the contagion of discontent, and the cravings for power,—to name but a few of the factors involved.

MOREOVER, AND OF the greatest importance, any enduring plan for developing industrial peace must reckon with the growing recognition on the part of the working classes that for reasons which they little understand there are rapidly developing conditions in the United States which make it increasingly difficult for a man to change his station in life. The employing class inevitably grows numerically less as technological advance requires more elaborate and more expensive apparatus for the manufacture of products. Then too, the high degree of specialization required for modern employment tends to separate the working classes into technically trained groups between which there are too few common denominators of experience to make transfer from one to the other at all practicable. Thus the position of the wage earner tends constantly to become more fixed and access to the employing positions tends to become far less possible than in times not long past. These conditions are all imposed upon a population which has been reared in the conception of America as a land of unbounded and unrestricted opportunity, where any man might become president and where possibility for advancement was unrestricted by any factors except individual ability and individual merit. America still remains a land of opportunity and a land of promise for self-expression of the individual man to greater degree than is true of any other land upon the earth's surface, but it is decreasingly so. The separate facts are known to a multitude of our citizens, but there is little understanding of their implications except among a few.

From a great number of possible examples I have taken labor unrest as a single illustration of the American tendency to classify ills by superficial symptoms rather than by thoroughgoing diagnosis. Wherever we turn to study normalities or maladjustments of mankind in such problems as war and peace, obedience to law or crime, mental hygiene or insanity, democracy or despotism, individualism or collectivism, nationalism or internationalism, we find understanding correspondingly needful and correspondingly difficult. Thus it comes about that few have time or energy to seek understanding and fewer have the background of knowledge and the mental acumen to acquire it. This is the significance of the statement in the report of President Hoover's Research Committee on Social Trends, which declares:

". . . . Modern life is everywhere complicated,but especially so in the United States, where immigration from many lands, rapid mobility within thecountry itself, the lack of established classes or castesto act as a brake on social changes, the tendencyto seize upon new types of machines, rich naturalresources and vast driving power, have hurried usdizzily away from the days of the frontier into awhirl of modernisms which almost passes belief.

"Along with this amazing mobility and complexity there has run a marked indifference to the interrelation among the parts of our huge socialsystem. Powerful individuals and groups have gonetheir own way without realizing the meaning of theold phrase,'No man liveth unto himself.' "

In connection with such an indictment, which must apply particularly to our American system of higher education, the question arises immediately whether it is deserved. In response, the colleges must plead guilty, especially to the charge of "marked indifference to the interrelation among the parts of our huge social system." The criticism cannot so fairly be made that our colleges have not done well the things they tried to do as that they have been trying to do other than the most consequential things. Only recently have we begun to pay as much attention to the basic culture necessary for a new civilization as we were giving to the luxury culture designed as an ornament for generations past. As always in change from one practice to another, there is maladjustment from which the colleges are definitely, if slowly, emerging.

There is real basis still, however, for criticism. The reign of science in its development of the scientific method has rendered incalculable service to the cause of education in defining how truth should be sought and in revealing how fallacy may be exposed. Unfortunately, nevertheless, up to the present time this method has dealt so exclusively with static things that its principles are inadequate when applied to changeable human nature. There has been occasional recognition of this among some of our outstanding scientists. Dr. Herbert E. Ives pointed out a few years ago, in an address upon research in applied science, that many of the characteristics necessary for success in human relationships are a positive detriment in scientific research, adding that "the electrons, protons and photons with which modern physics works cannot be stampeded by any emotional appeal." On the other hand, it might be added that accomplishment in the field of human relations cannot be successful except as the persuasiveness of emotional appeal is utilized to supplement the arguments of logical deduction.

Herein lies the greatest present-day dilemma of the college, that it has become responsible for two entirely different and sometimes contradictory functions. It cannot legitimately restrict its efforts to a training for an extension of the boundaries of knowledge. Knowledge once acquired is dependent upon understanding and discriminating interpretation and use if it is to be made of advantage to mankind. The colleges which have been established, endowed, and supported by society cannot reasonably disregard these obligations to society. They are responsible indeed to a degree never yet formally recognized for much more than training the discoverers and provers of knowledge. They cannot justifiably ignore qualities of character, sensitiveness to values we call spiritual, or attributes of personality among those of scholastic accomplishment who apply for admission. They cannot, in their official awards of merit, logically remain oblivious to those most likely to influence others by attributes supplementary to pure intellectualism such as variety of interest, breadth of comprehension, and human sympathy. Through men of these qualities are the fruits of knowledge given their widest distribution. Through men of this type does the college most directly serve democracy. Through men of this type may the claims of education be given appeal to public interest and to public support.

As societies at different times and places differ widely, so educational procedures have differed widely at different times, and so they differ at the present day in different areas of the earth's surface. Consequently, the word education has many interpretations, and a multitude of definitions have been given to it. The processes of the liberal arts college are devised in the theory that education fundamentally is for the purpose of safeguarding the values which the community has acquired in the past by toil and struggle, adding its due meed to these. Communities, however, are made up of individuals; so education in the liberal college concerns itself primarily with developing and directing the minds of individuals to the end not only that they shall have knowledge but that they shall likewise have intelligence. An intelligent man must have knowledge, but a man may have vast stores of knowledge and yet not be intelligent. Intelligence will demonstrate to any man that he does not and cannot live to himself alone. Consequently the college becomes responsible for developing a social consciousness in the minds of men upon whom its influence is operative.

Probably throughout history the distinctions among educational systems among different peoples have been in the conception of what constitutes truth. At any rate, this is so in contemporary times. If final truth is conceived to have been revealed in regard to the pre-eminence of a hypothetical racial strain, as among one great people in Europe, or in regard to the exclusive right to existence of a single social stratum, as among another great people, or in regard to the ideal form of government as elsewhere, then in any one of these cases we must grant that all agencies of education should be marshaled in propaganda, training, and discipline to compel the acceptance respectively of one or another of these doctrines. If, on the other hand, as in limited portions of western Europe and in the Anglo-Saxon countries, truth is held to be the ultimate of all ideals, approachable but never fully attainable, in search for which an individual or a race possesses itself of intellectual strength, moral stamina, and spiritual refinement, the theory and practice of education must be quite different.

Again, the theory and practice of education must be interpreted very differently according to whether we conceive of life in its long continuity and in its changing aspects or whether we yield simply to its contemporary exigencies. In the one case we will adopt the theory of the so-called "liberal" education, while in the other we will tend toward the vocational type and make effort to prepare a man for a given profession or for a given trade. Great, however, as are the problems of adopting the former practice, the problems of doing the latter effectively are almost insuperable and must become more so. In the self-contained community of a century ago, there were combined classifications of professional, agricultural, and industrial workers to the number of hardly more than a score. As contrasted with this, the last national census shows a classified index of occupations numbering above twenty-five thousand. In single concerns under the NRA, managements not infrequently find themselves subject to half a hundred involved and intricate codes. Analogous circumstances could be enumerated in considerable numbers. Under a multitude of such conditions applicable to every field of activity in human life, the liberal college argues that that form of education is most desirable which develops its men as a contingent force and gives them such training as will make them available as shock troops to meet any emergency which may arise, rather than trains them simply for one single branch of service. In other words, an education in regard to the general principles by which life has been lived and ought to be lived is likely to be more profitable to society at large than any other, if this education can be combined with enough mental discipline to give fortitude, and enough inspiration to give that form of idealism which constitutes spirtual vision.

It is to be remembered, meanwhile, that truth is a gem of many facets, the brilliancy of any one of which is dependent upon the skill with which the others are cut. Thus the scientist and the artist and the philosopher and the poet and the mathematician and the musician, among others, all have their respective parts to play and their especial surfaces to cut, if the diamond of reality is to have symmetry and beauty. It is with such considerations that we must deal in interpreting the functions of the liberal college,—functions inclusive of but far greater than the production of pure scholarship or intellectual brilliancy; functions designed for cultivating wisdom and for developing men of understanding.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1934 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1913

October 1934 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

October 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

October 1934 By Martin J. Swyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

October 1934 By Jack R. Warwick

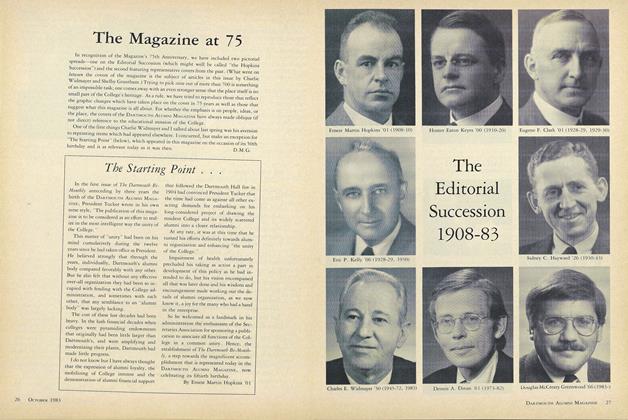

Ernest Martin Hopkins '01

Article

-

Article

ArticleSummer speakers examine 20th-century life

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleOral Exchange

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleDean of All Americans

April 1993 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

JUNE 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleBad News for Our Readers

October 1943 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Defense

January 1941 By The Editor.