Department of History

A POPULAR WEEKLY recently remarked that Governor Winant of New Hampshire held the all-time record for length of service. The Governor would be the last to claim that distinction. From 1777 through 1817, for forty years, there were only seven chief magistrates of the state, and three held office for eight years or more. Around these three—Meshech Weare, John Langdon, John Taylor Gilman—and two others—John Sullivan and Josiah Bartlett—turned the history of the state in the last quarter of the 18th century, and it was only natural that they should have had something to do with Dartmouth College. The one most concerned was Governor Gilman.

There were several reasons for the interest, of one sort or another, in Hanover and its doings. For one thing, politics were taken seriously then—although everybody didn't vote—and the attitude of the College community was of real significance in the state, not only in itself but as an influence on the training of the most frequently heard speakers of the period, the clergy. Again, the College was always in need of help, especially in the disrupted days after the Revolution, and turned to the legislatures of this and other states. And there was, finally, that ambiguous clause in the College Charter, which in naming the original board of trustees included "John Wentworth, Governor of our said Province, and the Governor of our said Province of New Hampshire for the time being."

GOVERNOR'S SELDOM PRESENT

Today, as we see in the General Catalogue, it is commonly understood that all governors of New Hampshire have always been Trustees of the College, ex-officio. They have seldom attended meetings of the board, but still they belong. All this was not so clearly understood by that earlier College, and for twenty-one years after John Wentworth crossed the state to Hanover in 1773 no governor met with the board, and for thirteen years after he fled on board a British man-of-war in Portsmouth harbor, there was no official connection between the State and the College. It seemed to have disappeared, and been forgotten, like that other provision of the charter which still requires the President, Trustees, Professors and Tutors to take an oath to support "his Majesty's Person and Government."

During the long term of Meshech Weare, the first President of New Hampshire, there was an additional reason for not maintaining official representation on the board, beyond the one of uncertainty of interpretation. There was so little contact between some of the towns of the Connecticut Valley and the Exeter government that Hanover changed its name to Dresden and claimed to be in Vermont. Some of the local leaders held office under that highly doubtful authority. Eleazer Wheelock himself was a justice of the peace; his son-in-law, Bezaleel Woodward, was one of the principal agitators, and though he was careful to resign his college connections, nevertheless public opinion held the College definitely involved. As a consequence, supplications for aid from the New Hampshire legislature received little attention, and the eventual collapse of the scheme left the College in an embarrassing situation.

. The second term of John Langdon, in 1788, saw the College Trustees determined to go a long way in smoothing things out. In August they voted to membership "his Excellency John Langdon, President of the State of New Hampshire," not as governor, however, but to fill an ordinary vacancy. President Langdon refused to serve, but in this term the College secured the first College Grant of what is now the town of Clarksville, an expression of interest in the institution if not of liking for its officers or their political opinions. John Sullivan, his terms sandwiching those of Langdon, was quite different in his attitude. Eleazer Wheelock had helped him ferret out "lurking Emissaries" of the paper money faction in 1787. In that same year he had tried to persuade the legislature to journey up the valley from Charlestown to look over the College; he was largely responsible for the First College Grant. Now, elected himself again in 1789, the Trustees voted him an LL.D. on August 26, and on August 27 "resolved as the opinion of this board that the President of this State for the time being is in virtue of the Charter of right a trustee of this College and it is the desire of this board that he attend our meetings as such so far as his situation will from time to time admit." General Sullivan couldn't find time to come, but the position of the President (soon to be called Governor) on the board had been settled at least in theory.

JOSIAH BARTLETT HONORED

Every effort was made to induce the next President, Josiah Bartlett, to take an active interest in the College. John Wheelock congratulated him on his election, and urged him to sit with the Trustees in August. Bartlett returned thanks, and many elegant phrases about the merits of education, but could not come. At Commencement he was voted an A.M. (while Alexander Hamilton received an LL.D.), which was sent to him by the hand of Professor John Smith. A year later President Wheelock wrote again expressing fear that his letter of a year ago never reached him but supposing Professor Smith told him of the degree! Again he invited him to attend commencement, as a great favor, "but it belongs to us only to propose, and submit the matter to your wisdom; as you have the weighty affairs of government to occupy your attention." In 1792 Bartlett was urged again—a little more briefly—and received that year, again in absentia, the degree of Doctor of Medicine, to honor him as founder and first President of the New Hampshire Medical Society. All this failed to soften the heart of the old Signer; there is no trace of any reply from him after the first letter. In all probability he was unable to forget the bitterness of Dresden period, and the prominent role he had played in averting armed conflict and keeping Vermont and New Hampshire within their present borders, through some devious alliance with Ethan and Ira Allen. Furthermore, his Universalist tendencies were not in harmony with the stern orthodoxy of Hanover.

In 1793 an opponent appeared to run against Bartlett for governor, John Taylor Gilman of Exeter. He got a few votes, and won unopposed the next year. Born in 1753, he had received what education the public schools of Exeter afforded. His father, a shipbuilder and merchant, Treasurer of the State all through the Revolution, was one of the most prominent men in New Hampshire. Clerking in the paternal office when news came of Lexington and Concord, he joined a company of volunteers as a sergeant, and marched off for Cambridge, spending the night (appropriately enough), at Braggs Tavern in Andover, Massachusetts. The rest of his revolutionary experience was purely civilian, but he served in the state legislature, the Federal Congress, on the state Committee of Safety, on various boards, both national and local, and as state treasurer after his father's death in 1783. Unlike his gubernatorial opponent later on, he was not a Signer of the Declaration of Independence, but many accounts tell of the emotion that overcame both him and his audience when he read the document aloud from the steps of the Exeter meetinghouse. In the state Convention of 1788 he was one of the leaders in securing the ratification of the new constitution, and finally as a reward for these long services became governor in 1794, to be re-elected till he had served eleven consecutive terms—enough to hold undisputed the all-time record for New Hampshire, without the three terms more he served during the War of 1812. A staunch Federalist all his life, unlike his brother, Senator Nicholas Gilman, he became in his later years the physical embodiment of the passing order, with his dignified appearance and eighteenth century costume—too much so for some of the rising young Federalists like Daniel Webster.

Governor Gilman, by 1794, was already well disposed toward Dartmouth College. He knew and liked John Wheelock, and was to become very close to him indeed. On the original board of Trustees had been Peter Gilman, also of Exeter, who not only was a remote cousin and near neighbor, but the stepfather of Ann Taylor, the Governor's mother. Furthermore, there were other ties between Exeter and Hanover in John and Samuel Phillips, benefactors not only of the two academies at Exeter and Andover, but for many years constant helpers and Trustees of Dartmouth. Gilman himself gave to the Exeter Academy the land on which the school was built, and served for over thirty years as treasurer and President of the Board of Trustees. And -finally he had a son in the sophomore class at Hanover. This interest in the College took active form after his election, when he rode up over the hills to receive the degree in person of Master of Arts, and to sit with the Trustees as governor and ex-officio member. The next year he brought the legislature to Hanover, but coming back for Commencement was another matter. Apparently he felt some hesitation about that ceremony, and the annual meeting of the board, for not till 1799 did he return, receiving then the degree of LL.D. At this meeting, and his next in 1804, he took a more active part, and served on several committees.

The next election saw him out of office. The intricacies of banking and politics, the whirl of the new century, and the political skill of John Langdon proved too much for him, till the opposition to the embargo and the War of 1812 swept him back into power. However, his services were not lost to the College, since he was elected a permanent trustee in 1807. In that capacity, he felt freer to attend, and he missed only two meetings, either annual or adjourned, in the next eight years. When the first attack came on John Wheelock, in 1811, he was one of three who opposed the resolutions, and in the dreadful August meeting in 1815, he with Stephen Jacob only voted against the investigation and removal of John Wheelock, and found it necessary to leave by the early morning stage before the election of a new President. That was the last time he sat, in any capacity, as a Trustee, but his friendship for Wheelock, while it prevented his acting with the dominant group on the old board, did not bring him to disregard the future of the College, or the political complexities of the situation. He remained, therefore, entirely neutral, refusing either to attend or resign, and as a consequence was of great help to the College faction, by making it harder for the University Trustees to obtain a quorum, and by not creating a vacancy which would have been filled by the "enemy." Not till the successful verdict by the Supreme Court in 1819 did he resign, to live peacefully for another nine years in Exeter.

His only son, John Taylor Gilman, Jr. 1796, died childless, but Gilman graduates of Dartmouth from other lines of the family have been numerous. Allen Gilman, 1791, of Exeter begins the list, and Charles H. Gilman, 1917, of Maine ends it. One of them, of course, was the great grandson of Governor Gilman's brother and the son of Edward H. Gilman, 1876, a man also born in Exeter, Joseph Taylor Gilman, of the class of 1905.

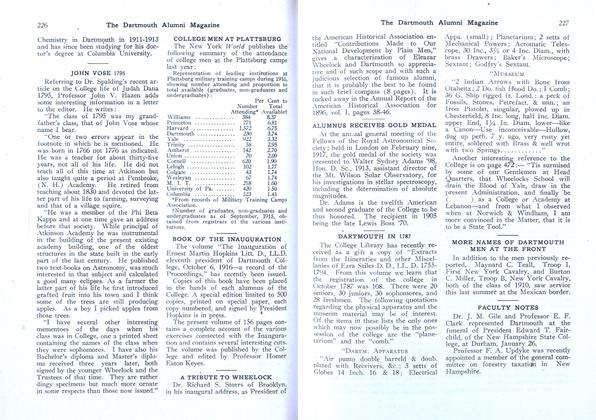

John Taylor Gilman

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

December 1934 By Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1934 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

December 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

December 1934 By Martin J. Dwyer, Jr.

Prof. Herbert W. Hill

-

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday Program in June

March 1938 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday

February 1939 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleHANOVER HOLIDAY 1947

April 1947 By Prof. HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday 1948

March 1948 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleNeed a Change of Pace?

April 1952 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL