[The Profession of the Fine Arts—Number Three in the Year's Series]

THE ADVICE OF one of my friends, a sculptor, to a student seeking his council regarding a career in that profession was to stay away from it unless he could not be happy in anything else. He was one who had experienced the discouragements, perhaps more than his share of them, common to all who do creative work. Yet he is not unhappy. On the other hand he, I am sure, has periods of very extreme happiness. It is such periods, even though they are set off by the despair of many failures, that persuade men into the practice of the fine arts, striving for the adequate expression of ideas and foregoing in most cases the material rewards that would be expected from an equal amount of time and energy applied in a more commercial direction.

Art is certainly not the pursuit for anyone who wants to make money. There are so many better ways. It is rather the pursuit for anyone who wishes to experience in the greatest measure possible moments of the purest freedom in spite of the world's exactions.

Michelangelo complained bitterly of the hardships and discouragements of his work and had to be bullied by th'e Pope into the completion of his greatest achievement. Yet one cannot conceive of this monumental genius who captured painting, sculpture, architecture and poetry all in a lifetime finding an outlet for his passionate energy in any other fields than these. Joseph Conrad asserted that he did not enjoy writing, yet it is certain that he could not have enjoyed life without it. Tschaikowsky, a lawyer until he was thirty, was willing to sacrifice what in material welfare probably was and assuredly is now a much more comfortable profession than music. And so it is true of a vast majority of those engaged professionally in the fine arts today. They are, or should be, content to gain in the satisfaction, uneven as it may be, of a creative expression what they may lose comparatively in a possible position of economic stability. To put it in another way they are staking their happiness in large measure on what is to come from within themselves as against rewards resulting and apart from the work itself.

THERE IS A great deal of trash written about the aesthetic emotions, their stimulation and fulfillment in painting a picture. If the painter feels such, he does not know what it is. What he feels definitely is the same response to the achievement of an orderly structure that is felt by the carpenter, the cabinet maker, or the mason.

The object of painting a picture or writing a poem or composing a symphony has to do largely with the attainment of a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. I like to consider this a usual state of being, not peculiar by any means to the artist, but common to all who work at something that they like very much, and foreign certainly to those whose pleasure lies chiefly outside their work.

It would be as ridiculous to insist that painting or writing or designing are the only endeavors the reward for which is in the doing as it would be stupid to argue that an artist is always poor and exists solely on the spiritual satisfaction of his works. Many creative artists have earned a very comfortable living by their art alone. A few have attained to positions of considerable wealth. I may cite Rubens among them whose house in Antwerp was a palatial

structure and who lived luxuriously, travelled a great deal and entertained in his vast studio distinguished men from the whole of Europe. Unfortunately such figures have been rare. For the most part artists in all the branches labor hard and long and get little for it. It is simply that most of them are concerned more with the integrity of their expression than with the molding of that expression to fit a possible commercial demand. A condition exists, however right or wrong, that the commercial demand for a fine work of art is far eclipsed by the popular demand for what is obvious, superficial and consequently transitory. It is as much of an exception to find a sincere artist concerned with supplying such a demand as it is to find an industrialist manufacturing a product in response to a belief that it will prove an actual benefit to humanity. Many artists today find it necessary to supplement their uncertain income by teaching painting, giving music lessons or in fact doing almost anything which will round out a living and permit them sufficient time to carry on their work. Most painters of any importance have taught and have liked to do so. They have considered it part of their routine and have felt rightly that the contact with young talents is valuable to master as well as students.

This impulse to spend one's time painting on canvas, manipulating chunks of clay or hewing at a block of marble is briefly the response to the persistent urge of some men to give expression to, to communicate in fine rhythm of sound, color, or words their enthusiasm and understanding of life. It seems that many human beings when they are moved or stirred would wish to talk about it. Insofar as an individual is sensible to and animated by his cumulative experience and by virtue of his ability to give it significant expression he is an artist and the degree that he is great will depend upon the universality of his understanding and his technical ability to express it. I believe this is as true of painting and sculpture as it is of music and literature.

I suspect that no small part in the total satisfaction of creative achievement lies in its recognition and praise by our fellow men. Some have been absurdly sensitive to the reaction of the world at large to their work. Cezanne, whose work today is in every important museum, and who went through his whole life lonely and misanthropic because of the absolute public indifference to it, was so childishly delighted when some neighbor was complimentary in his studio that he gratefully pressed the admired picture upon him as a gift. Years later, incidentally, it was sold by the neighbor for an astonishing sum. There was only one man in France at that time who considered Cezannes' work important—and that man was Cezanne.

IT HAS BECOME legend to think of an artist whether he be painter, writer, sculptor, or musician as a long-haired individual with a flowing tie, continually lost in deep meditation and far removed from an awareness of what goes on in the world about him. His manners are supposed to be bad, his taste exotic, his stomach empty, and his morals questionable. And he is supposed to never do a full day's work. Aside from his being in personal appearance no different from anyone else, he must, if he is a sincere artist, work very hard indeed. One characteristic that is common to all who have ever arrived at anything in the fine arts is, I should say, an avidity for hard work, a prodigious industry, and a tenhour rather than a six-hour day. They have had little time for the polite stupidities of the drawing room or the endless and extravagant discussions of the professional intellectuals; and the bohemian conviviality that we hear so much of is more typical of the gay playboys of artistic circles than of the actual producers. The social contacts of these men are for the most part with fellow artists and sympathetic friends—interesting and stimulating people of the various professions. They are, as are most craftsmen, decidedly clannish—for an artist is before all else, a craftsman. Artists are free agents and happily their vacations are when they wish to take them. But there is no such thing as a vacation in the accepted sense of the term. One never gets away from one's work no matter what the circumstance and one doesn't want to for each day's experience involves an observation and an evaluation which will be later turned to account. An artist's contribution should result from, as it were, the orderly flowering of his plan of life.

Men like Daumier, Rembrandt, Bach, or Brahms were men who did not merely paint or make music but were simple men of great human understanding and sympathy whose work was a reflection of their whole experience and who worked tirelessly and continuously for a mastery of the tools of their craft. And this must be as true of the important artists of today as it was of the great masters of the past.

WITH THE ADVANCE of civilization it becomes more and more apparent that the arts will assume increasing importance to other than those professionally engaged. As the material needs of mankind are more fully met, as men find themselves with a greater degree of leisure there will be felt a greater need for those activities of the mind which make for a fuller life and a higher intellectual functioning. Inasmuch as a work of art is seasoned not only with the personal philosophy of the artist himself but is conditioned by the whole social background and the drift of contemporary life, it is reasonable to dispute the antiquated idea that art is exclusive, socially aristocratic and for the few. It is, on the other hand, a matter for the average man's consideration, rather vigorous than refined and distinctly from the soil rather than the salon.

The history and appreciation courses given in our colleges and universities have done much to stagnate a natural tendency in young people for selfexpression in the fine arts. One cannot learn to experience the thrill of an El Greco or a Beethoven Symphony by hearing someone talk about it. It is small wonder that most students sleep through such lectures. I did so myself and I slept soundly and well and was not aroused by any disturbing response to the works of art which were monotonously crowded upon our attention. One does not have to play the flute to enjoy chamber music nor paint a picture to delight in a Vermeer. But somehow one should be made to feel that these things are very close to us. A lump of clay in one's hands will prompt a manipulation of it and subsequent manipulations will be governed by an increasing critical analysis of the fitness of its growing parts. Critical faculties will be stimulated and as they develop through future and varied evaluations appreciation will be more intelligent and more honest. The practice and appreciation of the Fine Arts is quite briefly the adjustment and organization of the parts on the artist's side and the participation in the experience as revealed in the completed work on the part of the public. Thus in a sense to do is to appreciate more fully. And as the material from which all art is compounded is from our common response to nature in the broadest sense, an art education should have as much philosophy on the menu as it does cadmium yellow, metaphors, or counterpoint. The painting of an apple depends as much on the taste of the apple as it does on its visual appearance and a fine drawing of the nude figure demands as much wisdom as it does anatomy.

THE OPPORTUNITIES and rewards for college men in the fields related to the humanities are as attractive to some as they are inconsequential to others. It depends entirely on one's point of view. One man would rather design something than sell what someone else has designed. A third would rather try to control the activities of both while a fourth would be content to do nothing but theorize about the motives of all included. Nobody takes the last one too seriously. Under the present set-up we certainly can't get along without the second and third and it is becoming generally felt that the first is quite as important as any, even in the practical sense.

"Church Supper, 1933" In the collection of contemporary American Art of the new Springfield (Mass.) Museum of Fine Art. One of the best known oil paintings by Paul Starrett Sample '20.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1934 By Frederick William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

February 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

February 1934 By John C. Allen

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS TID-BITS

January 1924 -

Article

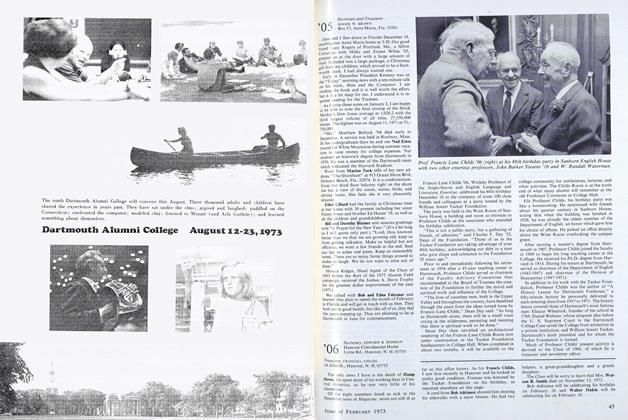

ArticleFrancis Lane Childs '06, Winkley Professor

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Article

ArticleRetirement

January 1975 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1979 -

Article

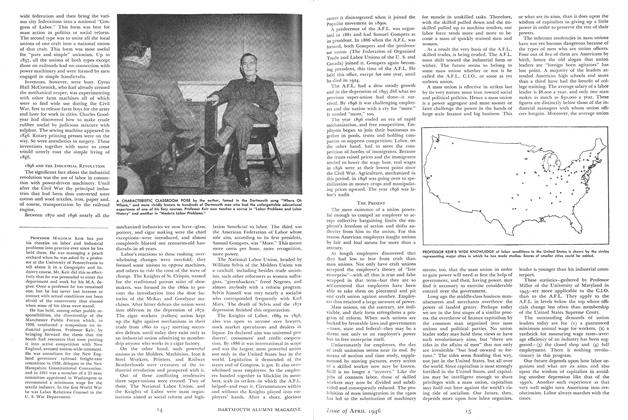

ArticleA WEATHERVANE FOR THE LIBRARY TOWER

MARCH, 1927 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

April 1946 By Parker Merrow '25.