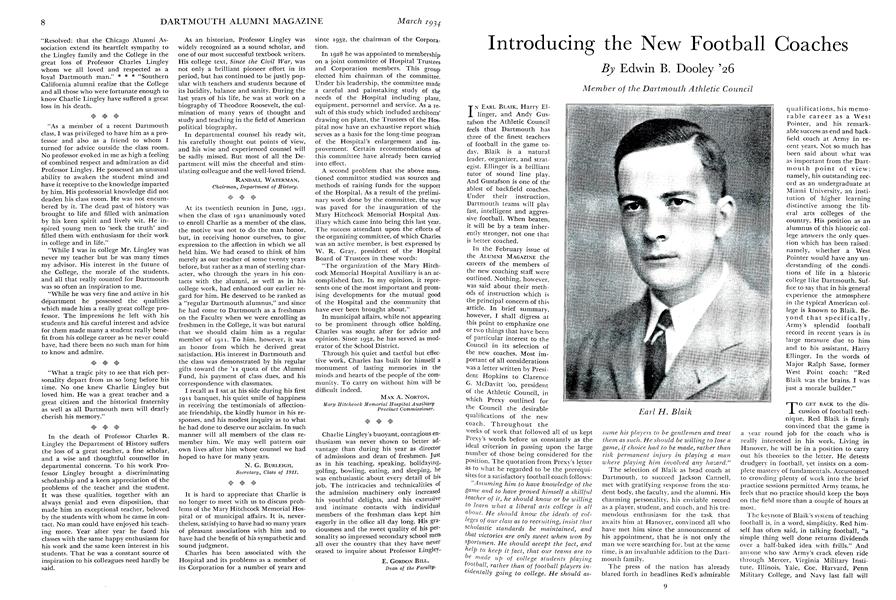

Member of the Dartmouth Athletic Council

IN EARL BLAIK, Harry ELlinger, and Andy Gustafson the Athletic Council feels that Dartmouth has three of the finest teachers of football in the game today. Blaik is a natural leader, organizer, and strategist. Ellinger is a brilliant tutor of sound line play. And Gustafson is one of the ablest of backfield coaches. Under their instruction, Dartmouth teams will play fast, intelligent and aggressive football. When beaten, it will be by a team inherently stronger, not one that is better coached.

In the February issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE the careers of the members of the new coaching staff were outlined. Nothing, however, was said about their methods of instruction which is the principal concern of this article. In brief summary, however, I shall digress at this point to emphasize one or two things that have been of particular interest to the Council in its selection of the new coaches. Most important of all considerations was a letter written by President Hopkins to Clarence G. McDavitt 'oo, president of the Athletic Council, in which Prexy outlined for the Council the desirable qualifications of the new coach. Throughout the weeks of work that followed all of us kept Prexy's words before us constantly as the ideal criterion in passing upon the large number of those being considered for the position. The quotation from Prexy's letter as to what he regarded to be the prerequisites for a satisfactory football coach follows:

"Assuming him to have knowledge of thegame and to have proved himself a skillfulteacher of it, he should know or be willingto learn what a liberal arts college is allabout. He should know the ideals of colleges of our class as to recruiting, insist thatscholastic standards be maintained, andthat victories are only sweet when won bysportsmen. He should accept the fact, andhelp to keep it fact, that our teams are tobe made up of college students playingfootball, rather than of football players incidentally going to college. He should assumehis players to be gentlemen and treatthem as such. He should be willing to lose agame, if choice had to be made, rather thanrisk permanent injury in playing a manwhere playing him involved any hazard."

The selection of Blaik as head coach at Dartmouth, to succeed Jackson Cannell, met with gratifying response from the student body, the faculty, and the alumni. His charming personality, his enviable record as a player, student, and coach, and his tremendous enthusiasm for the task that awaits him at Hanover, convinced all who have met him since the announcement of his appointment, that he is not only the man we were searching for, but at the same time, is an invaluable addition to the Dartmouth family.

The press of the nation has already blared forth in headlines Red's admirable qualifications, his memorable career as a West Pointer, and his remarkable success as end and backfield coach at Army in recent years. Not so much has been said about what was as important from the Dartmouth point of view; namely, his outstanding record as an undergraduate at Miami University, an institution of higher learning distinctive among the liberal arts colleges of the country. His position as an alumnus of this historic college answers the only question which has been raised: namely, whether a West Pointer would have any understanding of the conditions of life in a historic college like Dartmouth. Suffice to say that in his general experience the atmosphere in the typical American college is known to Blaik. Beyond that specifically, Army's splendid football record in recent years is in large measure due to him and to his assistant, Harry Ellinger. In the words of Major Ralph Sasse, former West Point coach: "Red Blaik was the brains. I was just a morale builder."

To GET BACK to the discussion of football technique, Red Blaik is firmly convinced that the game is a year round job for the coach who is really interested in his work. Living in Hanover, he will be in a position to carry out his theories to the letter. He detests drudgery in football, yet insists on a complete mastery of fundamentals. Accustomed to crowding plenty of work into the brief practice sessions permitted Army teams, he feels that no practice should keep the boys on the field more than a couple of hours at most.

The keynote of Blaik's system of teaching football is, in a word, simplicity. Red himself has often said, in talking football, "a simple thing well done returns dividends over a half-baked idea with frills." And anyone who saw Army's crack eleven ride through Mercer, Virginia Military Institute, Illinois, Yale, Coe, Harvard, Penn Military College, and Navy last fall will readily agree that simplicity played a very important part in the Cadets' devastating attack and unusually strong defense.

With but a tew exceptions, the Army team of 1933 was made up of 1932's substitutes. Red and Harry took those "subs" and fashioned them into as fine a team as West Point has ever seen. It was a small team, as college units go, short on weight, but long on ability. In almost every game it played it was outweighed. Yet it ran up 21 points on Yale and 27 on Harvard, at the same time keeping its goal line free of alien cleats. Only in the final game of the season with Notre Dame was Army defeated. The South Benders, physically more powerful than Army, swept to victory on the wings of a blocked kick. All through that colorful and memorable struggle, which thrilled some 75,000 fans, the blocking and tackling of the West Pointers was most impressive. Army's line, far smaller than that of Notre Dame, demonstrated a knowledge of for- ward wall technic that was most gratifying to any student of football. And the Cadet backfield on offense and defense was not only inspiringly but so well drilled in its individual and collective assignments, that its play was almost flawless.

The style of offense employed by Army under Blaik's tutelage strongly resembles that of Pittsburgh teams under Jock Sutherland—a fact which makes Gustafson's presence on the coaching stafE more valuable. Andy was Sutherland's backfield mentor and right hand man at the Panther institution and consequently he is well equipped to carry out Blaik's conceptions of offensive strategy. Categorically, Red employes the Warner system, generally using a single wing back offense but also employing the double wing attack, plus those innovations which he himself has seen fit to add. Like most successful coaches, he stresses offensive football, not only because it brings results but also because in his own words, "it's more fun for the boys." Every Army team the writer has seen in recent years has been scoring minded. That is to say, from start to finish they were out to score touchdowns, and they did.

IN STRESSING OFFENSE, Blaik does not neglect defense. "I like a strong, flexible defense," he says, "not only because it is good football but also to insure the peace of mind of the team's supporters. There's nothing so terrible as watching a two touchdown lead go up in thin air." The forward pass as an integral part of a team's running attack is one of Red's pet convictions. The Army team of 1933 was feared for its passes. Johnny Buckler had the annoying habit of throwing deadly passes while travelling full tilt. Then again he would cross up the defending secondaries by shooting equally devastating "spot passes." The Cadets' well devised and perfectly executed running and passing attack completely bewildered opposing backfields and enabled Army to roll up impressive tallies.

Another strong weapon in the Blaik attack is the "quick-kick." A Blaik-coached quarterback is just as likely as not to call a quick-kick on the opening play of the game. Army teams have frequently picked up twenty or thirty yards by this simple expedient used opportunely. Perhaps the most important precept Blaik imbues into his men is the ability to think under pressure. One has but to scan the accounts of Army's games with traditional foes in the last five years or so to realize the part quick thinking played in staving off many an impending defeat.

On defense, Blaik is a strong exponent of the five man defense. Red probably has so much faith in an Ellinger coached line that he can't conceive of using seven men on the forward wall and consequently employs the popular 6-2-2-1 defense, occasionally swinging into 6-3-8 when necessity and circumstance demand. But regardless of the situation, he never uses the seven man line. If Harry's six men can't hold the fort, neither can seven of them. "Beat your opponent to the punch with speed and an intelligent application of the weapons of attack," says Red, "and you're bound to go somewhere." And that's what his teams have been doing. Ellinger is similarly minded and that is the chief reason why Army teams have been such perfectly coordinated ordinated units. Ellinger, like Blaik, believes in getting the charge on the forward wall. His men employ a hard, low, driving line charge with a "lift" to it that is aimed to bowl their adversaries back off their feet. Army's fast backfield could never have gone anywhere had it had a slow line in front of it. Speed is the keynote of an Ellinger coached line, with intelligence and aggressiveness on an equal footing. It is axiomatic in football that a six man line to be successful must be a charging line. And that's what Harry insists on above all else. Last fall, Army's light forward wall held the opposition to a grand total of 26 points in ten games. Considering the calibre of the teams the West Pointers were called upon to face, that small total registered by the opposition was a tribute to Ellinger's methods of instruction.

Army's style of attack in recent seasons has closely resembled that of Pitt. Blaik, a keen student of the game, believes in adopting the best features of various offenses. He was deeply impressed with the Panther's manner of advancing the ball and introduced many of their plays at West Point. In Andy Gustafson, Red has as assistant the man on whom Coach Sutherland relied to get his backfield functioning smoothly and effectively. The speed and deception of the Pitt attack are well known wherever football men gather. In addition to his work at Pitt, Gustafson has had experience as a head coach at Virginia Polytechnic Institute. His apprenticeship served under the direction of one of the greatest coaches in the game and his work as a head coach equip him admirably for the job of assistant to Blaik at Hanover.

The uncertainties of football are so innumerable and so varied that any kind of prediction as to the success or failure of a team made far in advance of its campaign is nothing short of absurd. Of one thing, however, all of us are certain and that is that Dartmouth under these men will play football in a way that is truly representative of our finest gridiron traditions.

Earl H. Blaik

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

March 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

March 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

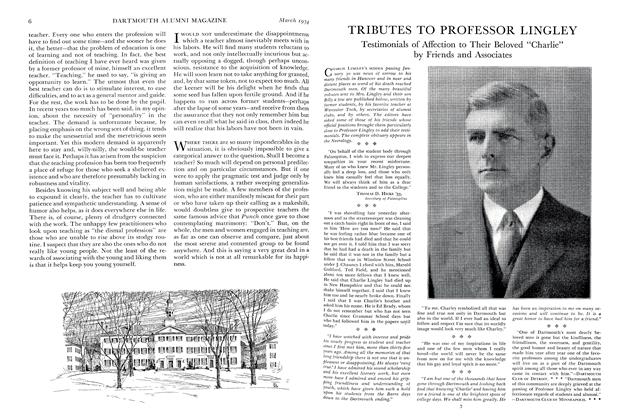

ArticleTRIBUTES TO PROFESSOR LINGLEY

March 1934 By Friends and Associates