This month my reading was restricted to American and Russian books. Some of them belonged to the type critics term proletarian literature; others were of a mixed nature. The result is that my list is not as unified as I would like it to be. Here it is for what it is worth.

l. America In Search of Culture. W. H. Orton. Little, Brown and Co. 1933.

2. The Great Tradition. Granville Hicks. Macmillan Co. 1933.

3. The American Adventure. M. J. Bonn. John Day Co. 1934. Professor Laski in his introduction praises this volume highlytoo highly in my opinion. He is getting to be very generous in his recommendations. Witness his laudation of Professor Brogan's Government of the People—a good study but not outstandingly so.

4. Roosevelt and His America. Bernard Fay. George Routledge. 1933.

This is an amusing but somewhat inexact volume by an intelligent French critic. His remarks on Harding, Coolidge, Hoover, and others of our industrial and financial leaders are shrewd and colorful. His picture of Roosevelt is a sympathetic one.

5. A Measurement of American Wealth. Robert R. Doane. Harper Brothers, 1933.

This is a specialized study aiming to give us a quantitative picture of our economic activity as a whole. It contains helpful tables and charts of the National Wealth, Income, Debts, Savings, Profits and Losses from iB6O to 1933. In style and clarity it is not too well written, but its content demands a close perusal.

6. Work of Art. Sinclair Lewis. Doubleday, Doran and Co. 1934.

An over-praised novel. Not by any means one of his major novels. It is dull in parts. The best qualities of Lewis as a novelist are not much in evidence in this work of art, although his weaknesses are only too noticeable. Those interested in hotels may like it, but I can recommend it only in the feeblest way.

7- The Collected Poems of Hart Crane. Edited with an Introduction (a good one) by Waldo Frank. Liveright and Co. 1933.

Somewhat difficult poetry in parts, but rich in poetic sentiment and metaphors. His long poem on The Bridge is very interesting.

8. Poems: 1924-1933. Archibald MacLeish. Houghton, Mifflin and Co. 1933.

quistador rises to magnificence in some lines and passages. I enjoyed this volume of poetry also. It included the best work of one of our most variable and distinctive poets. Some of his poems are marred by an occasional element of intentional obscurity. But at his est his poetry possesses nobility of emotion and rings true. His long poem Conquistador

9. Disinherited. Jack Conroy. Covici, Friede. 1933.

A proletarian novel dedicated to the disinherited of the world. It tells the story of Larry Donovan, and indirectly the class to which he belongs. The hazards and insecurities and tragedies of workers in the unsheltered industries are pictured effectively. Not a bad proletarian novel. It at least is as good as Nobody Starves by Catherine Brody, or Union Square by Albert Halper, or To Make My Bread by Grace Lumpkin, or other recent proletarian novels of this quality.

BOOKS ON RUSSIA: I. The Man From The Volga: A Lifeof Lenin. F. J. P. Veale. Constable and Co. 1933.

This and Ralph Fox's recent biography of Lenin are worth reading. Neither one is really a first-rate study of Lenin, but both are interesting.

2. The Great Offensive. Maurice Hindus. C. Smith and Haas. 1933.

A fairly objective and impartial study of the recent progress of the Communist Offensive in Russia. It is according to Hindus more successful on the sociological front than on the economic front. Very readable.

3. Red Medicine. Sir Arthur Newsholme and J. A. Kingsbury. Doubleday, Doran and Cos. 1933.

I would welcome more books of this nature on the various phases of the Russian experiment. We could do with many more specific and specialized and careful studies and fewer of the impressionistic type. The authors of this volume praise the socialized health work carried on in Russia, but unfortunately they are not as critical or careful in their observations as one would wish.

4. Twelve Studies in Soviet Russia. Edited by Margaret I. Cole. Victor Gollanz. 1933-

This contains a few very good chapters. 5. Time, Forward. V. Kataev. Farrar and Rinehart, 1933.

A very good specimen of the best of the proletarian novels turned out by the Marxian novelists of contemporary Russia. It gives a splendid picture of a day's record-breaking work in a cement mixing plant, and succeeds in catching the tempo and the spirit and the incentives and the difficulties of what the Russians are trying to do in the way of industrialization. It is informative to contrast this with the aver- age run of our proletarian novels.

LAST MONTH I criticized Humanism for I its philosophical weaknesses. The point I wanted to stress was that the hum- anists had failed to integrate their re- spective philosophies of nature and society and values and grace. They did not seem to do justice to the inter-relationships of these diverse philosophies. This was partly due to the fact that they were more interested in literary criticism than in philosophy. It was this that accounted for their inability to bring together their ideas into something like a satisfactory humanistic system. This of course is a difficult task under the best of conditions, and it was especially so in their case because the dualisms inherent in their positions were too absolute. The consequence was an unsatisfying philosophy of nature on the one hand and an equally inadequate philosophy of values on the other hand. Unless our philosophers can bring the world of nature and the world of values closer together we cannot have a comprehensive philosophy of either one or the other. I am not suggesting that this is easy to do. Perhaps it is beyond the attainment of man, for man is a creature forever destined to incompleteness in his philosophies and in his sciences. But once embarked on the quest of understanding the world we cannot renounce it despite the painful realization it is not possible to translate it into anything but an imperfect actuality.

At the same time we must try to do the best we can here as elsewhere. And above all we must guard against becoming victims to narrow particularisms and onesided specialisms. We must view things from the standpoint of our total knowledge. The danger of not doing this was brought home to me once more by some of the volumes in this month's list, particularly by the Marxian interpretation of American literature in The Great Tradition of Granville Hicks. It is this tendency which is one of the leading ideas in Professor Orton's America in Search of Culture. This is a serious analysis of the relationships between American society and art and culture. His point of view is similar to that found in the critical and biographical volumes of Van Wyck Brooks, or in Prof. Whipple's Spokesmen, or in Josephson's Picture of the American asArtist, or in the older books of Harold Stearns and other liberal critics. However, I do not find their discussions altogether convincing. American modes of thought and ideals of life are indicted in all these volumes. What they attack mainly is the dominance of economic and pecuniary standards in American life. We live in the externals too completely is the burden of their complaint. American civilization is conceived by them as being predominantly acquisitive and materialistic and economic in its animating incentives and ideals and rewards. They deplore the inner poverty of our aesthetic and spiritual life. We have no rich collective social life in which traditions and values productive of a vital art and philosophy flourish. They advance this as the reason why our literature and art so often lack imaginative richness and nobility of feeling. Professor Orton states it in this form: "Not even yet can Americans bring themselves consciously to admit . . . . that the general direction of their collective life since, roughly, the Civil War, has been diametrically hostile to the spiritual values they cherish," or, as he phrases it in another passage: "I have affirmed .... that the cultural capacities of the American people and the materials for their realization, are rich and full of promise. At the same time, I have affirmed .... that a living art cannot flourish in a dead society; that the artist needs, as artist, a social environment that does not affront his values at every turn, that is not altogether alien to him and his kind, that offers him the experience of human community rather than the necessity for escape for escape is not enough.

THERE IS ENOUGH truth in these criticisms to make us uneasy. It is unfortunate that so many American artists resort to escape as a way out o£ their difficulties, for "escape is not enough." Our poets and novelists and artists have something precious to contribute to our civilization. And if too many of them feel inhibited or frustrated or stifled that is our loss and their tragedy. More and more do we all come under the massive pressures of an industrialized and a mechanized and a materialistic social order. But for some reason or another we are not too successful in our efforts to direct this civilization so as to enrich the social and ethical and aesthetic and spiritual values of the good life. Even the institutions dedicated to these noneconomic interests of mankind are not performing their work any too well. They also have become too secular and external in their ministrations.

But surely our writers and artists have some positive responsibilities in this connection. Granville Hicks assumes that they are bound up with, the function of the writer not only to portray the life of the age in which he lives but also to change that life. I would accept the grain of truth in this if he did not limit it so much to the economic or if he did not insist that the changing be done along Marxian or revolutionary lines. It is undesirable to confine art or literature or thought to the Marxian dialectical system.

Nevertheless the Great Tradition of Hicks is the most thoroughgoing appraisal of American literature from the point of view of Marxianism that has been published in America. And if we grant him his premises his judgments are logical enough. One cannot but note, however, that his conclusions are implied in his premises and his judgments are inherent in his assumptions. He judges American writers, both of the past and the present, by his revolutionary Marxian yardstick. Naturally he is severe on those books which can be placed in the category of escape literature.

On the whole he is consistent in his theory. But his practice is more variable. He is forced often to go outside the. cycle of Marxian standards to use other criteria and standards. This I take it points to the inadequacy of these standards for any really complete critical assessment. Revolutionary considerations are only a part of the many factors the critic must bear in mind if his task is to be done with any completeness. Many forces beside the economic affect both writers and critics. Hicks would probably assent to this except that he would view as primary and determinative the economic forces operative in any given cultural situation. Human beings do not live or think in a cultural vacuum; neither o they carry on their multitudinous activities in such a vacuum. The thinking and the behavior of people take place in a cultural environment and mutually affect and are affected by that environment. I am not denying what the Marxian critics ffirm; my interest here is rather in affirming what they deny.

I" WOULD AFFIRM also that a critic must concern himself with the content as as the form of art and literature. Excellnce may be found in one as much as in the other. In general also, my preference is for artists who do not try to escape from the difficulties of the age in which they live. Yet I do not judge escape in itself as a sign of insincere or dishonest work. The poet or the novelist may escape sometimes from the civilization of his age and country because he finds little or nothing in such a civilization to nourish his spirit. But rather than allow himself to be suffocated by a civilization inimical to his vision of life and alien to his scale of values, he, by an affirmation of creative energy, may escape into a world more in harmony with his ideals. Such a world may be partly real or imaginary. Escape literature is not invariably a symptom of evasion. It may well be an expression of high courage. Of all the forms of life on the earth man is the only form possessing the creative power to escape from an unsatisfying environment —both in time and space. Forsooth a part of his greatness lies in that fact, and some of his nobler quests and achievements bear witness to its significance.

There is a tendency in modern thought to denounce indiscriminately this power of man, without realizing the new and fructifying dimensions to living and thinking which may come out of its creative use by poets and artists and even philosophers. A certain amount of the best work of man in his arts and philosophies and religions has been realized in this manner. Our critical yardsticks may sometimes be fearfully impertinent.

It appears to be a difficult thing for critics who work with a theory of strict economic determinism and concepts of historical inevitability to refrain from abusing them in their interpretations. That is the trouble with theories of determinism. Their proponents nearly always violate them. Such theories should include all the facts we know about human behavior. From the strict deterministic point of view the writers criticized by Hicks could not have written in any other way than they did, and I suppose Hicks could not have criticized them in any other way than he has done, and logically I can do no other than to question his Marxian analysis in the way I do, and so on forever. One cannot choose what is convenient to one's theory in a world of rigid determinism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

March 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

March 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleTRIBUTES TO PROFESSOR LINGLEY

March 1934 By Friends and Associates -

Article

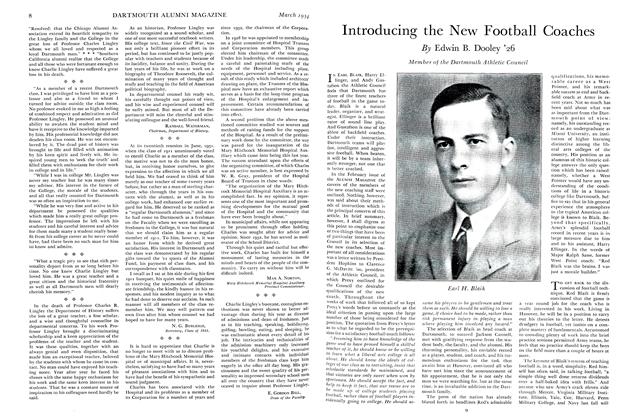

ArticleIntroducing the New Football Coaches

March 1934 By Edwin B. Dooley '26

Rees H. Bowen

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Books

BooksA HISTORY OF MODERN PHILOSOPHY

April 1941 By Rees H. Bowen