It has not been so obvious in these later days just what is the central and unifying force in the modern college curriculum. In olden times it might have been religion, or or perhaps the classics, each in its turn having occupied the throne among the seven or more liberal arts. And the reason for the prominence given to any one of these subjects in any given period was merely that the intellectual and social life of the day demanded that its leaders should be well versed in this subject. For some forty or fifty years colleges and universities all over the country have been breaking up or tearing down the old structure of learning as it was fitted to an older and more sedate period and setting up in its place a new structure which will be more in keeping with the times and their needs.

The new structure has not as yet been fully analyzed, but everywhere in this country institutions of higher learning are working at it. Education having been released from its old conceptions is now in process of new formation. Some institutions are trying this plan, others that, but the whole matter of the subjects of a curriculum and the method of presenting them best is finally settling down as a swarm of bees settles down about the queen The central principle seems to be the social sciences.

For some time within the past ten years people have been talking of a new humanism, not the "humanism" that brought into the curriculum the study of Greek in the original and the development of literary culture, but a study, as the word signifies of men and women and their place and interests and thought in the world in which they live. Education has passed in other words from the classes to the great body of people that inhabit the country; they need something more than a smattering of this and that, a bit of culture here and a bit of culture there. Dilettantism is no longer the sign of an educated man. The humanism which the social sciences teach seems to be the quality more desired.

In relation then to the social sciences the student will choose his electives. In economics, political science, sociology, history he will make a direct study of people—their actions, their thoughts, their institutions, and with something of a key to the age in which he lives and to ages which have gone before. Those who are most interested in the literary phases will do their work in that field, those who have natural ability and aptitude for languages will select their main studies in such a group. The groups will be larger, the subjects more varied, yet that which will be the most important will be the unity which holds these studies together. Any one speculation in this direction may be as good as another, for this is wholly speculative; yet as an attempt to prophecy what curriculum will be the most desirable in the future this is one interpretation.

It is evident to all who have had association with academic faculties that the one ever-present danger in curricular changes is that of the conflict between a narrow departmentalized point of view and the more liberal approach which is essential to any considerable progress. Surely the changes in the air in Hanover cannot be effectively approached, to say nothing of being successfully culminated, unless all departments of the faculty, and particularly those of the social science division, lower the bars of departmental isolation to the point where they are practically non-existent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

March 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

March 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Article

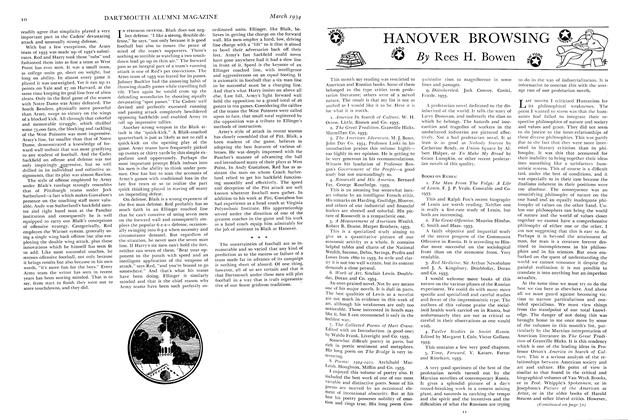

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleTRIBUTES TO PROFESSOR LINGLEY

March 1934 By Friends and Associates