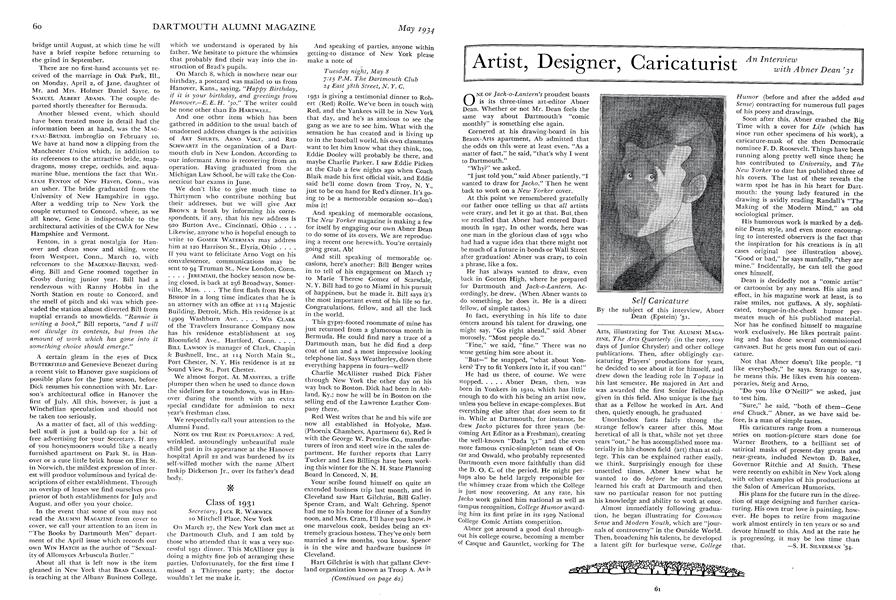

An Interviewwith

ONE OF Jack-o-Lantern's proudest boasts is its three-times art-editor Abner

Dean. Whether or not Mr. Dean feels the same way about Dartmouth's "comic monthly" is something else again.

Cornered at his drawing-board in his Beaux-Arts apartment, Ab admitted that the odds on this were at least even. "As a matter of fact," he said, "that's why I went to Dartmouth."

"Why?" we asked.

"I just told you," said Abner patiently. "I wanted to draw for Jacko." Then he went back to work on a New Yorker cover.

At this point we remembered gratefully our father once telling us that all artists were crazy, and let it go at that. But.then we recalled that Abner had entered Dartmouth in 1927. In other words, here was one man in the glorious class of 1931 who had had a vague idea that there might not be much of a future in bonds or Wall Street after graduation! Abner was crazy, to coin a phrase, like a fox.

He has always wanted to draw, even back in Gorton High, where he prepared for Dartmouth and Jack-o-Lantern. Accordingly, he drew. (When Abner wants to do something, he does it. He is a direct fellow, of simple tastes.)

In fact, everything in his life to date centers around his talent for drawing, one might say. "Go right ahead," said Abner morosely. "Most people do."

"Fine," we said, "fine." There was no sense getting him sore about it.

"But—" he snapped, "what about Yonkers? Try to fit Yonkers into it, if you can!"

He had us there, of course. We were stopped Abner Dean, then, was born in Yonkers in 1910, which has little enough to do with his being an artist now, unless you believe in escape-complexes. But everything else after that does seem to fit in. While at Dartmouth, for instance, he drew Jacko pictures for three years (becoming Art Editor as a Freshman), creating the well-known "Dada '5l" and the even more famous cynic-simpleton team of Oscar and Oswald, who probably represented Dartmouth even more faithfully than did the D. O. C. of the period. He might perhaps also be held largely responsible for the whimsey craze from which the College is just now recovering. At any rate, his Jacko work gained him national as well as campus recognition, College Humor awardmg him its first prize in its 1929 National College Comic Artists competition.

Abner got around a good deal throughout his college course, becoming a member of Casque and Gauntlet, working for The Arts, illustrating for THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE, The Arts Quarterly (in the rosy, rosy days of Junior Chrysler) and other college publications. Then, after obligingly caricaturing Players' productions for years, he decided to see about it for himself, and drew down the leading role in Topaze in his last semester. He majored in Art and was awarded the first Senior Fellowship given in this field. Also unique is the fact that as a Fellow he worked in Art. And then, quietly enough, he graduated

Unorthodox facts fairly throng the strange fellow's career after this. Most heretical of all is that, while not yet three years "out," he has accomplished more maerially in his chosen field (art) than at college. This can be explained rather easily, we think. Surprisingly enough for these unsettled times, Abner knew what he wanted to do before he matriculated, learned his craft at Dartmouth and then saw no particular reason for not putting his knowledge and ability to work at once.

Almost immediately following graduation, he began illustrating for CommonSense and Modem Youth, which are "journals of controversy" in the Outside World. Then, broadening his talents, he developed a latent gift for burlesque verse, College

Humor (before and after the added andSense) contracting for numerous full pages of his poesy and drawings.

Soon after this, Abner crashed the Big Time with a cover for Life (which has since run other specimens of his work), a caricature-mask of the then Democratic nominee F. D. Roosevelt. Things have been running along pretty well since then; he has contributed to University, and TheNew Yorker to date has published three of his covers. The last of these reveals the warm spot he has in his heart for Dartmouth: the young lady featured in the drawing is avidly reading Randall's "The Making of the Modern Mind," an old sociological primer.

His humorous work is marked by a definite Dean style, and even more encouraging to interested observers is the fact that the inspiration for his creations is in all cases original (see illustration above). "Good or bad," he says manfully, "they are mine." Incidentally, he can tell the good ones himself.

Dean is decidedly not a "comic artist" or cartoonist by any means. His aim and effect, in his magazine work at least, is to raise smiles, not guffaws. A sly, sophisticated, tongue-in-the-cheek humor permeates much of his published material. Nor has he confined himself to magazine work exclusively. He likes portrait painting and has done several commissioned canvases. But he gets most fun out of caricature.

Not that Abner doesn't like people. "I like everybody," he says. Strange to say, he means this. He likes even his contemporaries, Steig and Arno.

"Do you like O'Neill?" we asked, just to test him.

"Sure," he said, "both of them-Gene and Chuck." Abner, as we have said before, is a man of simple tastes.

His caricatures range from a numerous series on motion-picture stars done for Warner Brothers, to a brilliant set of satirical masks of present-day greats and near-greats, included Newton D. Baker, Governor Ritchie and A 1 Smith. These were recently on exhibit in New York along with other examples of his productions at the Salon of American Humorists.

His plans for the future run in the direction of stage designing and further caricaturing. His own true love is painting, however. He hopes to retire from magazine work almost entirely in ten years or so and devote himself to this. And at the rate he is progressing, it may be less time than that.

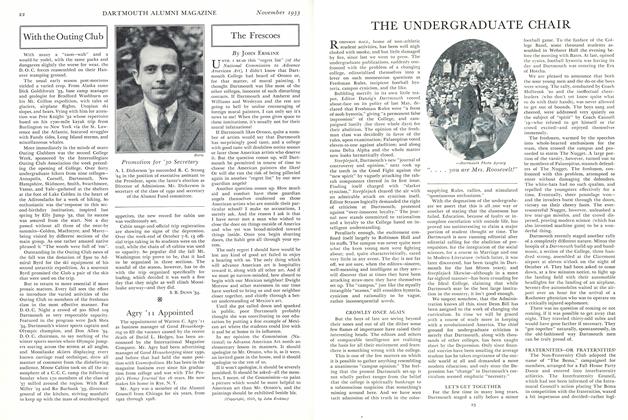

Self Caricature By the subject of this interview, Abner Dean (Epstein) '3l.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

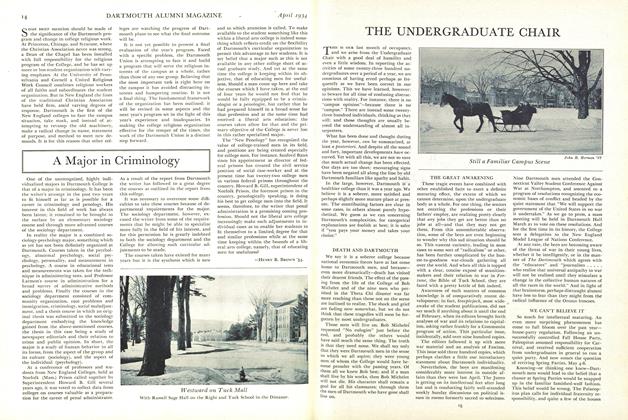

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1934 By Rees H. Bwen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1934 By Hanrold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

May 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

May 1934 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

May 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1934 By F. William Andres

S. H. Silverman '34

-

Article

ArticleTWENTY-FIVE JACK-O-LANTERNS

April 1933 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1933 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE GREAT AWAKENING

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleWE CAN'T BELIEVE IT

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleSOME CONSTANTS

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34