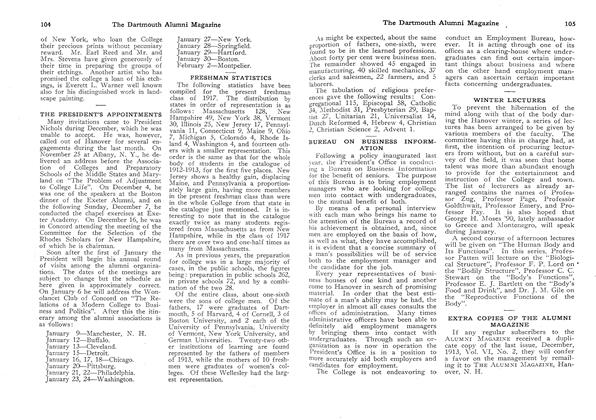

I BOVE THE CEASELESS clatter of the Broadway-Park Row trolleys and traffic, Francis H. Horah 'zs, sits in a high-ceilinged office in the stern Old Post Office Building in New York, directing the manifold activities of twenty expert lawyers, all Assistant United States Attorneys engaged in prosecuting and defending civil actions for the Federal Government. His formal title is Chief of the Civil Division in the Office of the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and his position incurs no little responsibility, as few will question its being the largest clearing house of its kind in point of important cases treated, obviously made so by the concentration of wealth, population and industry within its jurisdiction.

Frank's rise in the government's legal service has been swift. He is now completing his third year in public office. Even before he entered Dartmouth he had set his heart upon the law as his chosen profession. Although he is a native of Vermont, a staunch Republican stronghold, he is an enrolled Democrat and ardent rooter for the New Deal Administration. He was born May 18, 1900, in the little town of Saxtons River, nestled in the hills five miles from Bellows Falls.

He prepared for Dartmouth in Vermont Academy and St. John's Preparatory School, at Danvers, Mass., two years in each institution. In Hanover he was editor of the Aegis and The Dartmouth. He modestly disclaims inaugurating any radical policies during his editorship of the campus newspaper, but his college generation will attest the fact that many pithy comments emanated from his redactorial typewriter in the days which knew the early beginnings of the building renaissance and President Hopkins's intensive campaign for elevated standards of scholarship.

It was the pre-selective system era, and a time of vague unrest. Men who had been drafted in the war had returned to complete their courses. The late Warren G. Harding was in the White House. Prohibition was upon the country and the college tightened its discipline.

Frank never participated in formal forensic bouts during his college career, but was inordinately fond of an intelligent argument. The knowledge that one day he would practice law was uppermost in his mind, and now his post in the legal profession is one of singular distinction, especially for one of his comparatively tender years.

He fostered a flair for writing in college and served for two years as correspondent to the Boston Post. After graduation he went to Harvard Law School for one year, leaving those austere halls for the lure of journalism. Within a few weeks he had catapulted to the city editorship of the New Bedford Daily Sun and from there he gravitated to the copy desk of the Worcester Telegram.

He returned to Cambridge after a year's absence and graduated in 1926. Without wasting a moment he came to New York, and was associated with the law firm of Simpson, Thacher and Bartlett. This firm represents, among others, the Electric Bond and Share Company, one of the most sizeable of the country's public utilities. Frank's work there was mostly in connection with public utility security issues.

When former Federal Judge Thomas D. Thacher, a member of the firm, went to Washington as Solicitor General, Frank was appointed to his staff in June, 1931. This marked the initiation of his public service. The nature of his work in the new job was somewhat different in character. He pitched into briefing more than fifty cases for argument before the United States Supreme Court, involving millions of dollars which the government sought to collect as its due from alleged tax delinquents and others.

His next move came the following year when he went to the staff of Attorney General William D. Mitchell, in the tax division of that office. Here Frank briefed and argued various cases before Circuit Courts of Appeals in such cities as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, Chicago, Oklahoma City and San Francisco. Among the most celebrated litigation in which he participated was the settlement of the James Biddle Duke estate. Mr. Duke had established two trust funds for his daughter, the little-known Doris, now considered the world's wealthiest heiress. The government contended the trusts were only to take effect after the tobacco tycoon's death, which would place them in the estate tax category, and sought to collect the tidy sum of $6,800,000. In the final adjudication of the case, after the Philadelphia Circuit Court of Appeals had decided against the government, the United States Supreme Court, with eight justices sitting, voted four to four, thus sustaining the decision of the lower court. Chief Justice Hughes did not vote.

In San Francisco last December, through Frank's tenacity and convincing argument, the National Paper Products Company was ordered to pay the government more than $250,000 in income taxes. This followed after three separate Circuit Courts of Appeals had held against the government in similar cases.

The brilliant young Federal attorney succeeded to his present post last February. The men under his supervision prepare and argue cases involving income and estate taxes, certain customs, immigration and naturalization matters, suits on government contracts, and suits by World War veterans brought against the government to recover compensation for alleged disabilities suffered during their military service.

Four prominent cases pending adjudication, to which Frank has contributed no little effort and expert advice, are now the cynosure of all eyes from coast to coast. They are the suit against the United States brought by Transcontinental and Western Air Transport, complaining of Postmaster Farley's summary abrogation of the air mail contracts; the case of the Spotless Dollar Cleaners, Inc., wherein the government seeks to prevent the cleaners and dyers from charging prices lower than those provided in the code of fair competition under the National Recovery Act; the case of Frederick B. Campbell, wealthy lawyer and Westchester clubman, who seeks to restrain the government from withholding from him some $200,000 worth of gold bullion which the Chase National Bank of New York turned over to the Treasury Department after he was charged with violating so-called "gold hoarding" statutes; and last, but by no means least, the appeal by the government from Federal Judge John M. Woolsey's decision, handed down the day after repeal last pecember, permitting the importation into this country of James Joyce's "Ulysses," the most controverted book of the age. Judge Woolsey's scholarly and literary opinion was hailed the world over as a singular triumph for liberalism in the United States.

Although Frank has argued no cases in court in his present incumbency, he plans to do so in the fall. To date the demands upon him for executive work have prevented his appearance at the Federal bar in New York. In each of the four major cases enumerated, his chief, Martin Conboy, personal counsel to President Roosevelt when he was Governor of New York, has represented the Government.

Frank insists he has no political ambitions, has his bright blue eye on no definite political career, yet those who have observed his meteoric rise in public office thus far are inclined to doubt his unpresumptuous statements. He maintains his Dartmouth contacts through his permanent secretaryship of the class of '22, is unmarried, and resides in New York City.

Harry S. Casler '30

Assistant U. S. Attorney

An Interview with

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

June 1934 By John C. Allen, "Graham Whitelaw" -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

June 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Sports

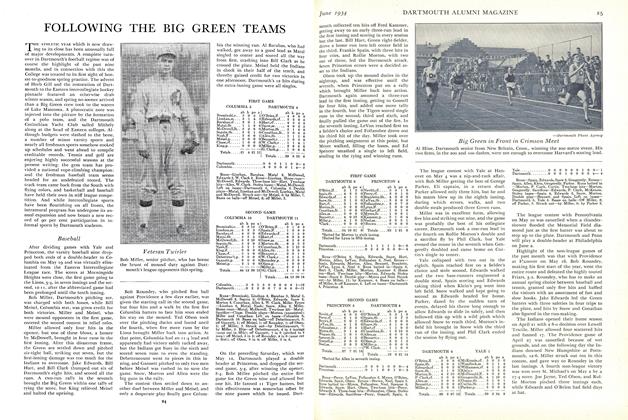

SportsBaseball

June 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

June 1934 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

June 1934 By Edwrd Leech, Ed Leech

Francis H. Horan '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleWINTER LECTURES

January, 1914 -

Article

ArticleHONOR SYSTEM ADOPTED BY THE THAYER SCHOOL

March 1920 -

Article

Article"A CHANCE TO LOSE" —THE DARTMOUTH

March 1942 -

Article

ArticleOldest Alumnus

May 1948 -

Article

ArticleOpening soon: the Hood

June • 1985 -

Article

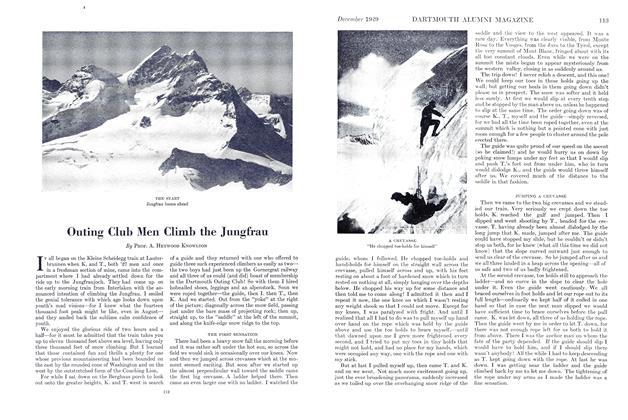

ArticleOuting Club Men Climb the Jungfrau

DECEMBER 1929 By Prof. A. Heywood Knowlton