IN A POEM in Spender's recent volume we find these lines: "Oh, Comrades, let not those who followafter,The Beautiful generation that shouldspring from our sidesLet them not wonder how after the failure of banksThe failure of cathedrals and the declared insanity of our rulers,We lacked the Spring-like resources of thetigerOr of plants who strike out new roots togushing waters,But through torn-down portions of oldfabric let their eyesWatch the admiring dawn explode like ashellAround us, dazing us with its light likesnow."

In this poem the poet thrusts forth the challenging possibilities inhering in the disorder of the social order not only on the American continent but also in every other continent. Different countries have chosen different methods of meeting the challenge of hope and rebuilding Spender sees in the contemporary world situation. These methods may range all the way from the New Deal of the United States to the Dictatorships of Central Europe or the ambitious Communism of Russia. How fruitful these methods are in realizing their respective objectives is a matter of conflicting opinion. All of them have their devoted supporters and belligerent advocates. The books I read this month were concerned largely with the claims and problems and hopes and purposes of the New Dealers and the Fascists and the Communists. Yet in practice all of them seem to be having greater difficulties in achieving their goals than was anticipated in advance. No one of them has been able to carry out- its plans in any thorough fashion. Neither has any one of them succeeded in lifting itself out of the depression except in a limited way. It looks as if this task of rebuilding is going to challenge the cooperative social intelligence and will and statesmanship of all of these countries for some time to come. We are probably at the beginning of an era in which the nations of the West—and perhaps of the East also—will strive to pattern their policies either after the more liberal and democratic traditions of Great Britain, France, and the United States, or after the authoritarian and hierarchical forms of Fascist Italy and Germany, or after the revolutionary planned economy of Russia. One senses that all of them, irrespective of the pattern, will be compelled to resort pro-

gressively to collective planning and conscious experimentation if they are to provide the necessary minimum of security and opportunity to their restless populations in the face of the insecurities of modern life. To do this is not going to be an easy matter. Knowledge, character, will, purpose will be needed as well as practical measures to translate these into effective instruments of achievement. Failure to do this may lead to disaster and anarchy. That seems to be the choice before us.

Students of the social sciences are vitally interested in all these attempts to turn into channels of human advantage the complex forces and interests at work in contemporary civilization. We have very few instances in culture history of deliberate, consciously designed and scientifically directed, large scale efforts to speed up the rate of cultural change. Russia, if not Italy and Germany, is attempting to change radically the whole culture of the country, not only in its externals but also in its motivations, incentives, disciplines, rewards, purposes, together with its moralities and arts and philosophies. Whether this can be done or to what extent it can be done we have very little pertinent knowledge from history to form any objective judgment. Of course it may be years before the results will be clear enough to throw much light on this particular question.. In his Popular Government Henry Maine states unequivocally that "the natural condition of mankind .... is not the progressive condition. It is a condition not of changeableness but of unchangeableness. The immobility of society is the rule; its mobility is the exception." Many other students of society besides Maine have been impressed by the tremendous inertia of social systems; their stubborn resistance to change, and what often appears as an irrational persistence of traditions, customs, institutions even when their former adaptive fitness has ceased. It is with extreme slowness that the essential patterns of culture change. It is true that Henry Maine wrote his book at a time when change was less übiquitous than it is now. Moreover, his illustrations were drawn from ancient and more static societies than those we have at present.

ON THE other hand we have Bernard Shaw saying in Major Barbara: "You have made for yourself something that you call a morality or a religion or what not. It doesn't fit the facts. Well, scrap it. Scrap it and get one that does fit. That is what is wrong with the world at present. It scraps its obsolete steam engines and dynamos; but it won't scrap its old prejudices and its old moralities and its old religions and its old political constitutions. What's the result? In machinery it does very well; but in morals and religion and politics it is working at a loss that brings it nearer bankruptcy every year. Don't persist in that folly. If your old religion broke down yesterday, get a newer and a better one for tomorrow."

Here Shaw cavalierly assumes that it is easy to do this sort of scrapping. The tough-minded realist here becomes extravagantly romantic. Yet precisely how much romanticism there is in his position no one can say with too large a measure of confidence. Be that as it may, there are a goodly number engaged in this scrapping business at present. Why and how and what for the scrapping is done may be answered best by reading some of the books on this month's browsing list.

1. Technics and Civilization. Lewis Mumford. Harcourt Brace Co. 1934.

This is Lewis Mumford's most satisfactory book. It is also one of the best books in English dealing with the rise and development of the machine and its confusing effects on Western civilization. It divides into three periods the centuries in which technics has been accumulatively affecting our civilization. These three periods are named after the usage of the students of prehistory, namely, the eotechnic, the paleotechnic and the neotechnic. The eotechnic covers roughly the period from the tenth century to the eighteenth century, the paeotechnic from the eighteenth to the latter part of the nineteenth century, and the neotechnic from about 1870 to the present. Each period is characterized by certain inventions and ideas and disciplines. The present neotechnic is based on the use of electricity for energy purposes and on metal alloys. I will not enter now into the justification for this division. Suffice it to say that the author draws heavily in his historical interpretations on writers like Sombart, Patrick Geddes and Veblen. This he does sometimes too uncritically as in his use of Sombart's distinction between "economy of need" and "economy of acquisition," and to a lesser extent on Veblen's concepts of vendibility and serviceability. I detected some errors of fact and a few errors of interpretations like this statement that time and space were to Kant categories of the mind. However these are not important enough to detract from the value of the book. Some of his generalizations and causal explanations and side remarks and criticisms are open to the charge of being based on incomplete analysis. He forsakes the task of historical description here and there, and as a result occasionally tends to generalize on a meagre basis of historical fact. The book is weakest in the first part, but it gets better as it comes nearer to our own day. His tentative predictions as to what may happen to mechanical inven- tions and similar changes in the future seemed to me to have much to say for them. I would disagree with some of his statements about the causal relationships between different parts of culture, although he does not at any time fall into the commonest fallacies of particularistic systems of determinism. He does not confuse sequences in events with causal relationships as some analysts of culture do. The best thing in the book is his attempt to show how science and technology have affected our ideas and attitudes and values. Both the direct and the indirect effects are discussed with a good deal of insight. The latter part of his discussion raises anew Veblen's old question of the conflict between technological or neotechnic realities and processes of thought and the pecuniary ideals and practices and modes of thought of business men and financiers. Mumford is of the opinion that the logic and practice of technics point to what he terms "basic communism." Here he approaches the position of the technocrats. Throughout it all, however, he has a wider outlook on the desiderata of a rich and satisfying civilized life. A perusal of a volume like this will reveal to the reader why so much scrapping is and has to be done by both individuals and groups. Read it by all means.

2. Aspects of the Rise of Economic Individualism. H. M. Robertson. Cambridge University Press. 1933.

Another splendid volume. It is not listed in Mumford's bibliography. I venture to say that if he had read this book he would have modified some of his statements about the earlier phases in the development of capitalism. This volume is in essentials a criticism of Max Weber (and his followers) historical generalizations concerning the relations between the Protestant Reformation and teaching and the spirit of capitalism. Robertson's criticisms of this interpretation of the emergence of capitalism is effective and damaging. It should be read along with Mumford's book.

3. The Economy of Abundance. Stuart Chase. Macmillan and Cos. 1934.

Chase is in danger of writing too much and studying and reflecting too little. This accounts for the fact that his recent books are somewhat superficial and repetitive. He possesses an acute mind of the accounting or bookkeeping type. He knows how to use his knowledge and ideas to turn out popular books. He is always concrete and clear and interesting. These are his good qualities. But his analysis never goes far enough; neither do his ideas go deep enough. Both his good and bad qualities come out in the present volume. It presents effectively his view that we are living in an economy of abundance, but that the majority of us do not enjoy the economic blessings of such an economy. The habits and practices and rules and purposes and institutions of the older regime of scarcity stand in the way. If we would only scrap these, so the argument runs, the scientific and technological powers at our command would be adequate in a few years time to give the average American a standard of living about the equivalent of $6,000 a year at the old 1939 level of prices. That is hopeful at any rate. But a great deal of scrapping will have to be done before this becomes an actuality. The weakness of the book is that the author does not discuss realistically enough the difficulties that must be encountered in passing over from a regime of scarcity to an economy of abundance. Holders of power under the status quo and beneficiaries of the present order are likely to offer potent resistance to the changed supported by Chase. Many sharp conflicts will probably delay considerably the passage from the insecure present to Chase's regime of abundance. There is a tendency in Chase to exaggerate the automatic features in modern industries. His figures conceal in disguise a certain amount of technological romanticism.

4. On Our Way. Franklin D. Roosevelt. John Day Cos. 1934.

President Roosevelt has done a modicum of scrapping himself in the last fourteen months. But he has not found it any too easy. Neither has it been free from difficulties and resistances. And these appear to be increasing rather than decreasing. This interesting volume of the President suggests that one of the objectives of his scrapping has been "a swing back in the direction of a wider distribution of the wealth and property of the Nation." Referring to the task which confronted him when he entered upon his work he says "The almost complete collapse of the American economic system that marked the beginning of my administration called for the tearing down of many unsound structures, the adoption of new methods and a rebuilding from the bottom up." The volume does not aim to do more than to bring together the series of messages and speeches which he delivered to both Congress and country in explanation of his various policies. As the title intimates, he is confident that we are "on our way." The destination may not be as uncertain as some of his critics imply for in his own words through his policies "has run a very definite, deep and permanent objective."

5. Permanent Prosperity: And How ToGet It. John Bauer and Nathaniel Gold. Harper and Bros. 1934.

The authors of this volume are convinced that the problem of the age is that of security. They argue for a new approach and a new purpose in our national economy if this problem is to be solved. Their program for realizing the permanent prosperity of the title includes a plan of public works designed to give the unemployed steady employment, and likewise a scheme for financing this plan by government control and if necessary nationalization of banking and credit institutions.

6. The American Farmer and the Export Market. A. A. Dowell and Oscar B. Jesness. University of Minnesota Press 1934.

I liked many of the chapters in this timely book. It is an informative treatment of the relations between American agriculture and the spread of economic nationalism. They are aware of the necessity of distinguishing immediate problems and temporary policies from long time problems and more permanent objectives. Worth reading.

7. Economic Reconstruction. Report of the Columbia University Commission. Columbia University Press. 1934.

This report has many excellent features. It contains the general Report of the Commission as well as a series of good articles by individual members of the committee. Such topics as the essentials and difficulties of economic planning, limitation of output and its dangers, the productive capacity of industries and effective demand for the products, monetary policy and the price system are handled with practical insight. Here and there the report questions the wisdom of policies directed towards restriction of output. It points out one danger of the N.R.A. which has not been given much attention. It is stated as follows: "In this connection it is important that the N.R.A. should not develop a permanent policy for the closer regulation of output by each industry in terms of its own particular interest. At all costs we must avoid a situation of competitive restriction of output between industry and agriculture, each seeking to improve its relative position, with consequences similar to those of the tariff wars between nations." A pointed analogy and danger.

8. Toward a United Front. Leon Samson. Farrar and Rinehart. 1934.

This is an attempt to work out a revolutionary United Labor Front philosophy for American workers. It is both a credo and a manual of action. The author endeavors to show that there has been a great deal of revolutionary energy in America, but that it has not been harnessed effectively to do real revolutionary work by a revolutionary labor movement with a realistic understanding of its economic interests and revolutionary role. The weakness of American radicalism in the past is conceived to have been its sentimental motivations and Utopian objectives. It had no roots either economic or cultural and was therefore subject to spasmodic but wholly ineffectual activity. There are some suggestive interpretations in the book, although I do not think its general thesis is sound.

9. World Resources and Industries. Erich W. Zimmermann. Harper Bros. 1933.

A substantial and helpful work to the serious student. One of the better books of the last year.

10. The Mainstay of American Individualism. Cassius M. Clay. Macmillan and Cos. 1934.

A splendid treatment of the problems of difficulties of American farmers, who are termed "the mainstay of American Individualism." Deserves a careful study.

11. New Governments in Europe. Vera M. Dean and others. Thomas Nelson and Sons. 1934.

I can recommend this volume to readers looking for a simple and reliable interpretation of Fascism in Italy, Nazi Socialism in Germany, Communism in Russia and similar dictatorial mixed movements in the Baltic States and Spain.

12. The Italian Corporative State. Fausto Pitigliani. P. S. King and Son, London. 1933.

Those familiar with the general features of Fascism in Italy will find this treatment helpful. It is marred by an unclear style. Otherwise it is reliably informative. It stresses the syndicalistic, corporative elements in the Fascist State and doctrines.

13. The New Church and The New Germany. Charles S. MacFarland. Macmillan and Cos. 1934.

A general and fair account of the struggles in ecclesiastical circles in Nazi Germany. The coordinating policies of the totalitarian National Socialist State have not been carried out too smoothly up to date.

14. Social Reformers. Adam Smith to John Dewey. Edited by Donald O. Wagner. Macmillan and Cos. 1934.

This would make a good companion volume to Professor Coker's Recent PoliticalThought recommended last month. It is a collection of well selected readings from the original works of the most significant reformers of the past 150 years. Each reading is prefaced by a brief biographical sketch. Many men in many ways have spent the best years of their lives in Shaw's scrapping business. But it is a delicate and difficult task.

15. Art As Experience. John Dewey. Minton, Balch and Cos. 1934.

A readable, fresh and worth-while discussion of art and its meaning in human experience as well as its significance in civilization. It is better written than most of Dewey's other books. His style is lighter and looser in structure. I enjoyed the last half of the book much more than the first.

"There is no test," says Dewey, "that so surely reveals the one-sidedness of a philosophy as its treatment of art and esthetic experience." Judged by this criterion Dewey's instrumental philosophy stands the test rather well. He has some sensible things to say about the place of art in a humane civilization. He stresses the direct, qualitative, unifying, creative elements in art as experience. No vital art can flourish in a civilization organized on an unsound basis and patterned after false ideals. Neither can an organic civilization flourish without the insights of art into the unifying possibilities of life and experience. Such are some of the ideas suggested by Dewey. I regret I have no space to give a more satisfactory review of this stimulating book. Worth reading.

16. The only books read for relief and unalloyed entertainment this month were a book of poems by Edward Doro (TheBoar and Shibboleth. Alfred A. Knopf) and P. S. Wodehouse's latest light volume Thank You, Jeeves. There is no need to commend this to lovers of the lighter novels of Wodehouse.

I have used my allotted space, so I hasten to draw my year's browsing to anend by a slight alteration in the wellknown lines of Belloc:"John Henderson, Critic, browser,Had lately lost his Joie de VivreFrom reading far too many books.He went about with gloomy looks:Despair inhabited his breastAnd made the man a perfect pest!"

An Outdoor Summer in Hanover The College Park your back yard. Cottage apartment for rent. College-supplied heat and hot water. E. P. KELLY WHITAKER APARTMENTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

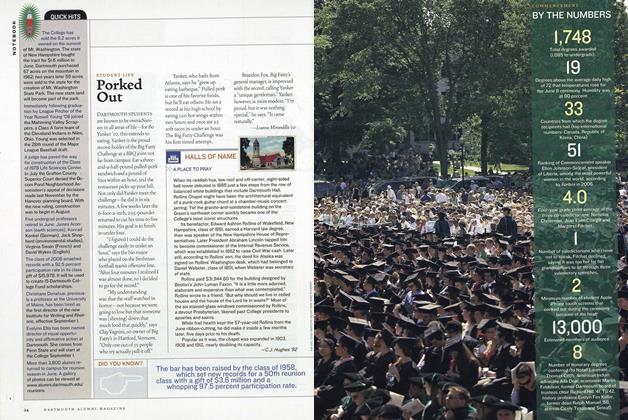

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

June 1934 By John C. Allen, "Graham Whitelaw" -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

June 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Sports

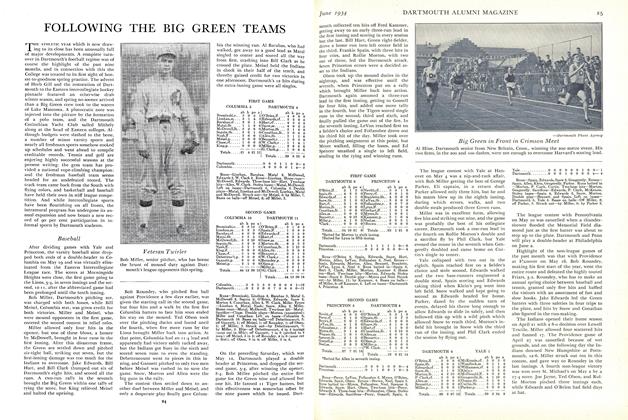

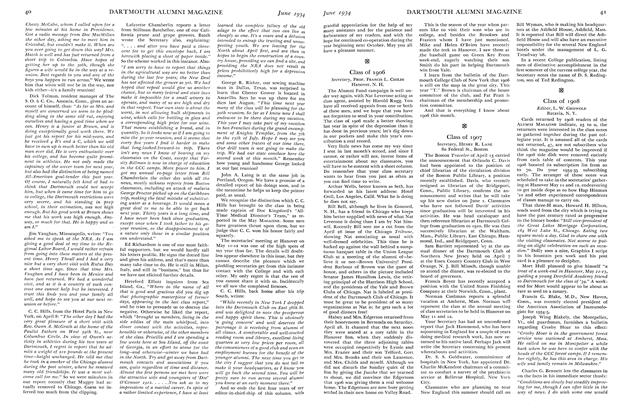

SportsBaseball

June 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

June 1934 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

June 1934 By Edwrd Leech, Ed Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

June 1934 By Arthur E. McClary

Rees H. Bowen

-

Books

BooksSOCIAL ORGANIZATION

January, 1931 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1934 By Rees H. Bowen