A NY RETURN TRIP to Hanover brings in equal measure its two kinds o£ equally pleasant surprises: the things that change and the things that remain. Strange —to us old-timers, now past our Fifteenth- how the momentary thrill of the one gives place to the abiding comfort of the other. A first view of the Baker Library or the gorgeous new Tuck School produces in- stant tingling excitement, but the sight of some familiar architectural monstrosity, squatting in a corner apart from the path of progress, gives reassurance and peace.

Coming up Main Street again, you are secure in the knowledge that all is much the same and as it should be. What if Phil's has given place to a beer garden, and the post office hopped across the street from Frank Musgrove's block to a palatial residence of its own? What if the Lambda Chi Alphas no longer meet in solemn conclave above Allen's Drug Store? Allen's itself is still there, and both the bookstores, and Scotty's—or another just like it.

Surviving the ravages of fire, Dartmouth Hall bears no outward semblance of change; but Ledyard Bridge, one of the grandest landmarks of them all, is done for. Today no doubt the traffic cops welcome the boys home in September as they whirl into town from Leb and the Junk. In our time you felt yourself really "back again" when you shook oif the cinders of the B. and M., set foot on the creaking timbers, smelled the good, strong smell of the old bridge, and made your choice between the gradual long ascent of Tuck Drive and the quick steep pitch of Wheelock Street.

The look and feel of the bridge was always right, coming or going. It welcomed us back and ushered us out. It sped us ofE on peerades planned for months in advance. Then there was no wealth of Harvard, Yale and Princeton games to choose from. It was Brown in Boston, perhaps, or Pennsylvania in New York— or even, believe it or not, the Carlisle Indians to wreck an other- wise stainless season. That was no age of rapid transit, either. You skimped for months for the one big toot; and if some hardy soul lost his all in a last minute poker game, more often than not he took his chances "blind baggage" or on the floor beneath a suitcase, serving as a smoking car bridge table. 'Hamp was considerably more than a couple of hours away and Bennington had nothing more stirring to offer than a battle monument. Neither beckoned alluringly after the day's last class or summoned a sleek roadster down the highway for almost any week-end in the calendar.

Naturally enough, we want the picture to stay as we remember it. We harbor, each of us, our own individual and unreason- able fancies, demanding that no harm shall come to them. But do we realize that what stands out most clearly in the mind's eye of one may not even exist in the recollection of another? An entertaining young lady by the name of Eleanor Early recently wrote a book, appropriately titled "Behold the White Mountains!" She takes the casual tourist here and there about the state, giving him history, local color and amusing anecdote for background. Then in the final chapter she brings him to the Hanover scene. There is talk of Sampson Occum and John Ledyard and the Earl of Dartmouth, who never saw and apparently had little idea of'what it was he was giving his name to. The author makes no mention of the Orozco murals. But she tells of the Dartmouth College Case and then breaks the news that the College paid for the services of counsel—Webster, Mason, Smith and Hopkinson—by commissioning Gilbert Stuart to paint their portraits. These selfsame oils, Miss Early says, now look down from the walls of Webster Hall. For all we know, they may have been there, unmentioned and unnoticed, fifteen or twenty years ago.

"Things That Remain"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFRAGMENTS OF TRUTH

October 1935 By Ernest Martin Hopkins '10 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

October 1935 By Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1935 By G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

October 1935 By Harold P. Hinman -

Sports

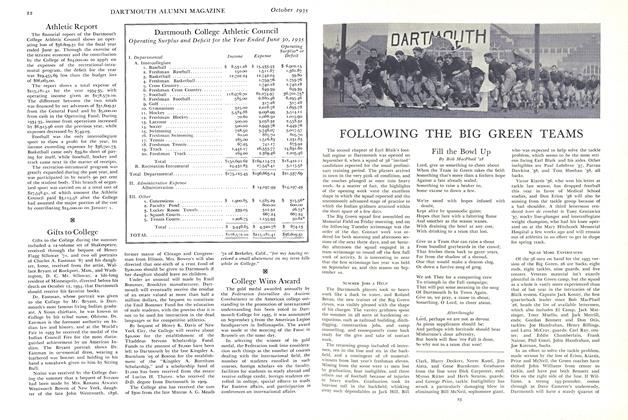

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1935 By C. E. W. '30 -

Article

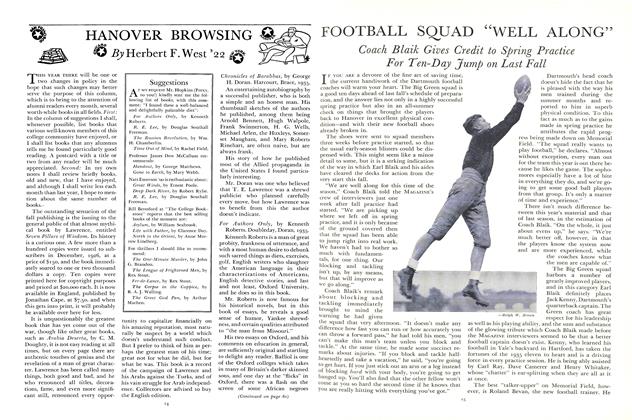

ArticleFOOTBALL SQUAD "WELL ALONG"

October 1935

Article

-

Article

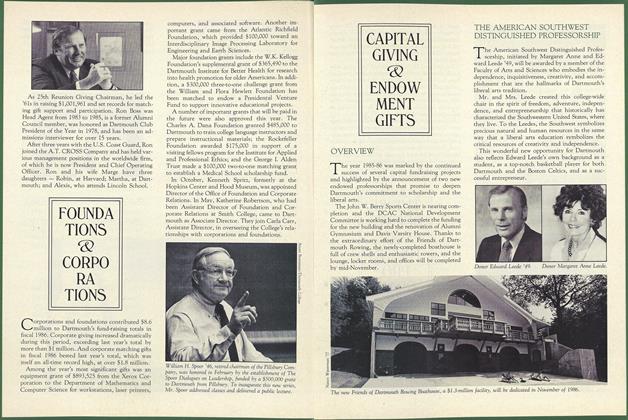

ArticleFOUNDATIONS & CORPORATIONS

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleFears, Faith and Hope

JANUARY 2000 -

Article

ArticleA Whole New Hood

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 -

Article

ArticleSome Things Never Change

OCTOBER 1999 By "Mom" -

Article

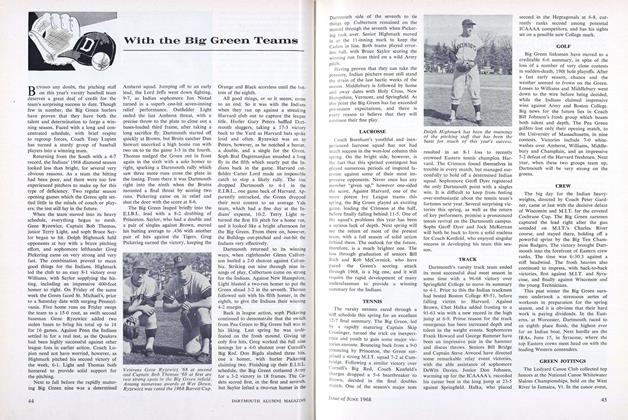

ArticleLACROSSE

JUNE 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Coming Month

March 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45