By Richard G. Wood '22. Orono: University of Maine, 1935.

Some of us remember childhood stories of Bangor on the Penobscot as the play ground of the lumber-jack and the he hole of the north," and in this volume we find the background of those rough-and- tumble days in the history of lumbering in Maine in its most prosperous years. This investigation, which was the subject of a doctoral dissertation in history at Harvard and is published as Number 33 in the Second Series of the University of Maine Studies, carries all the impedimenta of scholarship, with extensive and minute footnote references and a heavy and detailed bibliography. But if the general reader can overlook these earmarks of the budding Ph.D., can waive for the moment assurance that confirmation of a raftsman's likelihood of death by drowning is to be found in the Portland Eastern Argus for June 14, 1839, or by crushing while breaking a landing in the Bangor Daily Journal for May 21, 1855, he begins to catch the thrill of the story and to understand its human as well as its economic and historical significance.

Historically speaking, this volume not only makes a contribution to the general narrative history of the State of Maine but represents one more entry in the long list of frontier studies inspired by Frederick Jackson Turner's famous paper which was read at the meeting of the American Historical Association in 1893. As Dr. Wood has pointed out, Maine was the last frontier in New England, and her pine forests represented a special frontier in themselves. With this in mind the author has chosen to cover the period between the separation of Maine from Massachusetts and its admission to the Union as a state and the year when pine was largely replaced by spruce as Maine's chief lumber crop.

Most frontier studies have stressed the methods by which new lands have been made available to those who represented the advancing tide of exploitation and of settlement, and one of the most valuable chapters of this work is that which outlines the rather unique situation in this respect which existed in the timber lands in Maine. Between 1820 and 1853 there were in a sense three different land policies, for at the time of the separation Massachusetts retained one-half of the ungranted lands in Maine and proceeded to sell them at her own terms. Maine meanwhile established her own system, and in 1832 a further policy of joint-sale was inaugurated in some areas. This joint policy broke down in the early fifties, and in 1853 Maine bought up the last of the land held by the Bay State. This same chapter recounts the story of the Maine land speculation and panic of 1835. This incident has not been much emphasized hitherto, and is of peculiar interest as anticipating the general panic of 1837.

The book starts with an outline of the general topography of the Pine Tree State and a description of its river systems, which were the life streams of the lumbering industry. After dealing with the land policy, it goes on to discuss in clear and orderly fashion the different methods of getting the timber down and out of the woods; the spring drive with all its thrills and dangers, its complex system of log marks, its jams and dams and sluiceways; the methods of rafting and scaling, the use of booms, and the various types of saw mills; and in two final chapters deals with marketing of the lumber and the migration of the Maine lumbermen westward with the timber frontier. One of the surprising facts in Dr. Wood's account is the degree to which the individualism of the many small-scale enterprises was tempered by cooperative organizations which effected a common regulation of drives, log marks, use of booms, and improvements in water conditions.

Yankee ingenuity does not appear to have flowered in the lumber industry to the degree one might have expected. By far the best known invention native to Maine is the peavey, invented in 1858 by Joseph Peavey, a blacksmith at Stillwater. Dr. Wood has included a photograph of the monument of Joseph's grave, with its crossed peaveys and superimposed P forming a coat-of-arms in good Maine tradition. The volume includes several quaint contemporary pictures of life in the woods, several other photographs, and helpful maps. It makes a definite contribution to the frontier hypothesis, but of greater appeal to the general reader is the fact that it contributes to the economic and social history of our own northern New England country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1935 By Prof.Nathaniel G.Burleigh -

Article

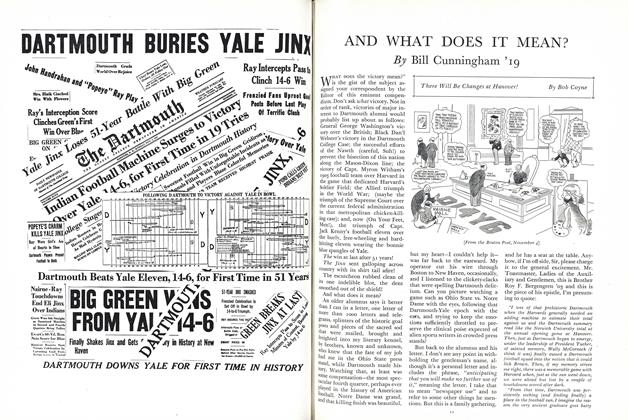

ArticleAND WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

December 1935 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

December 1935 By Edward leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesAll in the Day's Work

December 1935 By Claude T.Huck -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1935 By Harold P.Hinman -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

December 1935 By Josephine C.Chandler

Allen R. Foley '20

-

Books

BooksHIS EXCELLENCY, GEORGE CLINTON, CRITIC OF THE CONSTITUTION

May 1938 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksHANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE:

July 1961 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleTHE RIVER

APRIL 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleDRESDEN SCHOOL DISTRICT

JANUARY 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticlePOPULATION AND POLITICS

MARCH 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksVirgin Dip

June 1976 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksWine of Fury

November, 1924 By Eric P. Kelly -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSPEARHEADS FOR REFORM, THE SOCIAL SETTLEMENTS AND THE PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT 1890-1914.

JANUARY 1968 By PHILIP S. BENJAMIN -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksThe Regularization of Employment

May, 1926 By W. A. Griffin