By Sydney A. Clark. Robert M. McBride & Cos., New York, 1931.

No better book could be suggested as a "bon voyage" gift to the American traveler who embarks for Europe on a vacation, than this delightful volume by Sydney A. Clark: "Many-Colored Belgium." It 'will lend the ocean-weary passenger the means of spending in a delightful manner several of the monotonous hours of a transatlantic crossing. For it is not a book of erudition, its style is easy and charming; neither is it a dreary guidebook (it is essentially incomplete); it is not a book of long descriptions, for it evokes and suggests and stirs our imagination rather than giving us accurate pictures: with the subtle ease of a carefree "causerie" the author takes us along on his rambles through the main cities and the country side of Belgium.

The book should appeal to the average American traveler, for it teaches him hoie to travel. Mr. Clark is not a "rusher," he travels leisurely, he does not see "everything that has to be seen" or at least he does not tell us of everything: he knows that, according to Boileau "Le secret d'ennuyer est celui de tout dire."

He takes us to the "grand'place" in Brussels, this square unique in the world, overwhelmingly beautiful with the richness of its Renaissance house fronts, the sumptuousness of its Gothic city hall, the ground covered with the gorgeous color-display of the daily flower-market. With the author we sit at a "cafe" table and ponder: and suddenly, as if touched by a magic wand, the picture changes: the setting remains, but the flower-market has disappeared: we are carried back four centuries: the square is in uproar, thousands of commoners watch, with a restrained rage which the presence of Alva's Spanish army can hardly repress, the execution of their beloved leaders Egmont and Horn: the history of the Spanish rule in Flanders unfolds itself before our eyes.

Another chapter takes us to Bruges: we stroll along its dreamy canals and silent, narrow streets bordered with quaint old gabled houses: "Bruges-la-morte"; suddenly the canals are crowded with innumerable ships from all parts of the world, the quays are bustling with busy merchants: the scene is that of five centuries age: the burghers of Bruges are richer than kings and display lavishly their unlimited wealth. Soon afterwards political troubles and the receding of the sea cause Bruges' downfall and her trade and wealth and art pass to Antwerp.

And so we visit Ghent, Antwerp, the sea resorts: with keenly observing eyes Mr. Clark watches the people in their doings, he listens to their language, he reads the public notices on the street corners, nothing escapes his watchful mind: present day Belgium as well as its past becomes a living picture.

Flanders, the Northern half of Belgium has the cities with their glorious past, historical and artistic; it has the sea resorts and the rich beauty of its well cultivated fields; it has a flower industry more fully developed (though less advertised) than has Holland. Southern Belgium, the "Wallonie," has no such brilliant past; its cities are generally dull, but for twenty miles up and down the river Meuse at Liege, industry is roaring at full blast and at night the sky is lit with the glow of flaming furnaces; and Wallonie has the incomparable charm of its hilly country side, the delightful and imposing "foret des Ardennes" at an altitude of about fifteen hundred feet, covering an area of some sixty miles from North to South and as much from East to West, and, what is most important, its beauty is practically unknown to and untrodden by the common tourist.

Mr. Clark has both good common sense and a delightful sense of humor. His style is lively, colorful; he does not analyse, he remains superficial; he evokes pictures before the reader's mind: pictures of the present which he has seen, pictures of the past which he visualises in his imagination.

Sometimes one feels as if the author, in his desire to be striking, concludes somewhat daringly from casual observations to general statements. About half way through one may get slightly fatigued by the constant use of those witticisms and jocular remarks which at first make the reading so light and pleasant. Finally, one may get the impression that sometimes the author, in his acceptance of statements from historical sources, lets his imagination get the better of his spirit of critical discrimination. But, as has been said before, this is not a book of erudition; to quote Anatole France, "is it not a virtue in itself, just to be pleasant?" And this is indeed a most pleasant and delightful volume.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

October 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

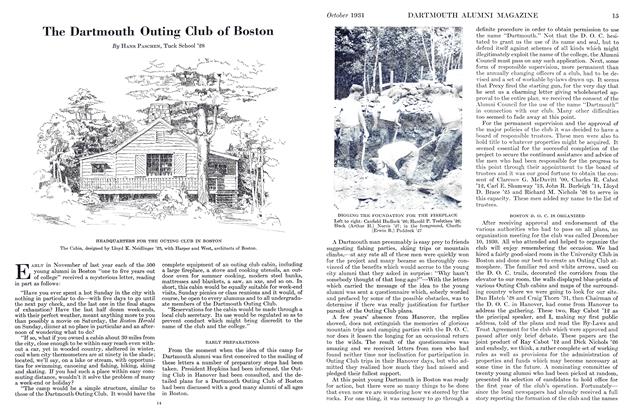

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

August 1921 -

Books

BooksAPPLIED PSYCHOLOGY

May 1934 By C. N. Allen -

Books

BooksTHE HEALING OF A NATION.

OCTOBER 1971 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksMONUMENTAL WASHINGTON: THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE CAPITAL CENTER.

JANUARY 1968 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksPROPAGANDA-ITS PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNIQUE

February 1936 By Henry S. Odbert '30 -

Books

BooksProf. Herman Feldman

March 1943 By Herbert Wells Hill.