THE FRATERNITY SITUATION .... DR. LITTLE .... CRITICISMOF CURRICULAR MATTERS . ... E. A. ROBINSON ....WEBSTER! AN A

Old Devil, Inertia

To the Editor:

One of the editors in the June issue commented on the recent fraternity report and made the statement that, based on the few letters received, alumni seemed apathetic and not greatly interested in whether national fraternities remain at Dartmouth or not. I am sure it will be a serious mistake to misjudge inertia for apathy. The natural reactions are usually to blow off steam verbally but rarely to get around to writing.

I have talked with a great many alumni and some undergraduates on the point at issue. Out of some hundred opinions I have heard expressed I have found exactly one who favors general abolition of national fraternities and I learned that his fraternity was a local at the time he joined it. The almost unanimous opinion I have heard is that: (1) The local idea will answer none of the conditions which are said to exist and must be corrected; (2) That Hanover is isolated enough now without making a local system compulsory; (3) If national charges are too high in some cases those groups can decide to go local to avoid them if necessary without penalizing every fraternity now at Dartmouth; (4) On the subject of finances the committee seems to have taken its position largely on the cost of the national affiliation which averages $45.00 per man for the three year period or about 1% of the cost of a four year college course, this relatively picayune item being no more important as such than any other §45.00 item in a student's budget.

I find no interest whatever in a local club system which might be similar to Princeton's or Harvard's (the only two protestant colleges of significant standing which do not have national fraternities) which offers not advantages to the undergraduate over the present system and which is based on insularity and exclusive ness.

Don't misjudge Dartmouth men on this subject. They certainly are not apathetic. In my experience a large majority will actively contend for the right to maintain the national affiliations of their societies.

572 Madison Ave.,New York City.

Notes on "Squash" Little

To the Editor;

I admired and respected Doctor Charles S. Little '91 so much that I almost hesitate to send you one or two incidents illustrating the things you ask for because they might seem trivial and frivolous; however, I will leave that to your judgment.

In the early days of Dr. Little's medical career, while on the staff of a Massachusetts mental hospital, "Squash" used to get rather bored with routine duties and mental concentration. He would then wander down to the hospital's power plant, pick out the biggest fireman who was there shoveling coal, tease him a bit, finally to the point where the fireman retaliated, and then they would have a good old-fashioned bare-hand boxing and wrestling match. When Little had put him squarely on his back and held him there until the fireman cried for mercy, Little, with great delight, would allow him up and return to his less strenuous duties. He feared no man.

While on duty with the A.E.F., following the armistice, he lived in a barracks to which were assigned a lot of junior officers. Often one came who was rather fresh and obstreperous, and Little was always the self-appointed guardian who put the man in his piace, no matter how powerful the young officer was. Little would always quiet him and end by picking him up in his huge arms, tossing him across a table onto a bed and holding him there until the officer cried for mercy. All problems of handling obstreperous personnel were easily cared for by Captain Little.

One other incident: at a base hospital at Savanay, France, "Squash" had charge of all building equipment and grounds. He had assigned to him a big group of German prisoners and I never saw any man get so much good work out of a group of rather reluctant workers as Little did out of those men. Another incident: we wanted to start an occupational therapy shop at the base hospital and had no materials to work with, so Little was given a leave and a detachment of sergeants and corporals arid told to go to headquarters or anywhere else in France and bring back material to start the work shop. He was gone about ten days and came back with a whole train which he had commandeered somewhere loaded with iron, copper, wood and every other conceivable material which he had salvaged at various depots in France—and at the throttle of the engine driving it into Savanay was "Squash" himself. In my opinion no other man in the whole of France without his great physical powers, mental ability and vast sense of humor could have accomplished this.

One of the most modest men I ever knew, Dr. Little was, at the same time, one of the most understanding and powerful personalities that have lived in our genera tion.

Butler Hospital,Providence, R. I.

Curriculum Questions

To the Editor: Dean Bill's article in the March issue must have raised a number of questions in the minds of some alumni. It would be significant to know whether or not the Curriculum Vivens had the official stamp of approval. If so, it is worthy of attention.

In the first place it seems unfortunate that the ALUMINI MAGAZINE should be made a medium for the criticism of the Washington Brain Trust. It is, of course, obvious that only reactionary administrators would agree with the Dean when he says that the cause of the liberal arts college has been thrown back at least two decades by the doings of the Brain Trust. One has only to look at such universities as Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia to see that efforts are being made in these institutions to provide well-trained men for important public posts. The Dean believes that the set-back was caused by "viciously narrow specialization." Without in any way implying a defense of the Roosevelt administration, one wonders if the Dean would appoint someone other than an agricultural specialist to the post of Secretary of Agriculture or someone unfamiliar with all the specialized problems of relief to the position of Relief Coordinator.

It also appears somewhat contradictory to imply in a defense of a new curriculum proposing to stress the social sciences that the experts in the social sciences who have been called to Washington are anathema to good government. One of the most logical goals of the serious student of any social science should be to put his knowledge to use for the general good of the country, if possible as a federal expert. The Dean prides himself on his ability "to profit by experiments performed by other people." If he is to make good his claim he should—if the Brain Trust must be mentioned—at least offer more constructive criticisms.

In outlining the reasons for the new curriculum the Dean writes:

"Apparently the Dartmouth faculty believes that before you can orient students,or build any lasting edifice in the socialsciences, it is first necessary to lay a strongfoundation such as will be furnished bySocial Science 1-2. Furthermore, althoughthroughout the country there is much talkof freshman courses which 'integrate' thesocial sciences, the Dartmouth faculty apparently believes that the student cannotintegrate several social sciences until hehas got something to integrate; in otherwords, until he knows at least a little bitabout each of these disciplines, can speaktheir language, and come at least to a hazyrealization of their method of attack." In one sentence the Dartmouth faculty is made to say that one cannot integrate things before having a "strong foundation." In the next sentence we find that students will be integrating "a little bit" or a "hazy realization" of each of the disciplines. But as the Dean says, you cannot integrate until you have something to integrate.

The word "integration" has been so bandied about by modern educators that it no longer makes sense. Unless one has the ability and the background of a Rosenstock-Huessy (whose appointment to the Dartmouth faculty is the brightest note in the Dean's article), the much vaunted "integration" of the social sciences only results in superficial glibness. Scores of examples could be given of "integrative" courses where the students have been exposed to different points of view and different symbols of the social scientists and where the result has been the production of nothing more than a sort of intellectual diarrhea.

There are few really first-rate social scientists who would for a moment claim that they had "integrated" their own field of specialization with any other field or with any two or more other fields. Such integration is achieved only after years of hard work. It cannot be poured into the heads of men fresh from high school by a year's lectures and readings. Probably fewmen on the Dartmouth faculty would dissent from this opinion. If so, it is unfair to ask the students to do the impossible. Doubtless the faculty has by no means overlooked this fact and it is probably genuinely striving somehow to break down the lamentably artificial barriers that now separate the various disciplines. The alumni would be interested to know precisely what is happening and why.

Finally the Dean informs us that we can now divide humanity into a half dozen types and that we shall soon be able to give a cum laude to a man because of his "character and personality." (The distinction between the two terms has apparently already been integrated.) This typology is supposedly derived from the Progressive Education Association. But the eight year plan of the P. E. A. is by no means primarily concerned with the resurrection of the problem of typology as the Dean implies. The six types are very incidental guides to be used in the program. Probably no two people, even in the P. E. A., would agree on a typology. The history of psychology shows that such a rigid classification of human nature is utterly futile. The particular typology under consideration seems especially bad and to use such types in the awarding of degrees would be psychological nonsense as well as academic folly.

The Dean says that the elements of a strong character and personality "mean eminent success after graduation." He should bear in mind that "character" and "promise" are relative terms, determined entirely by the local, national, or general cultural standards of the day and by the particular group of persons issuing the judgment. Hence any attempt to award degrees for character would result in the unwarranted imposition of the prevailing Hanover values on the unsuspecting student body. A typology is useful in a Fascist state but has no place in a democracy—a real democracy.

These are only some of the more specific questions raised by the Dean's article. One would like to know what the Dean really believes "education" means and what he feels is the function of a liberal college.

Teachers College,Columbia University

Connecticut College

A Star Contributor

To the Editor: The article "Curriculum Vivens" by E. Gordon Bill in your March issue was very interesting to me. Dean Bill has the happy knack of writing upon a difficult subject in about as interesting a way as is possible. I remember how several years ago he would write articles using statistics from the freshman class and weave them into the most enjoyable account in the MAGAZINE. I urge more articles written by E. Gordon Bill.

6 Salisbury St.,Winchester, Mass.

Plea for Phi Beta Kappa

To the Editor: Gentle reader, if thou hast not read the summary of the report of the Committee for the Survey of Social Life in Dartmouth College, pass this by. As a member for a quarter of a century of Phi Beta Kappa, our oldest national fraternity, whose chapter at Dartmouth, -the Alpha of New Hampshire, has enjoyed an honorable existence for 150 years and on whose chapter roll are writ the names of a large percentage of Dartmouth's most distinguished sons, I view with alarm the recommendation by the majority of the Committee that there be an "ultimate dissolution of these national connections" and I shudder at the thought of their adoption, for I must assume that the Committee's recommendations extend to all chapters with national affiliations and that the chapter of Phi Beta Kappa along with all the others has not in the opinion of the Committee conformed to their "minimum requirements."

I studied the report at great length in an endeavor to discover our sins and omissions.

Have we failed to maintain "a scholastic chapter standing equal to the average of the three upper classes"?

Oh, no!

Are we not intolerant of "all practices conducive to dishonest academic work"?

We certainly have that reputation!

Do our members fail to secure adequate privacy and opportunity for study?

Don't be foolish!

Have we ever been charged with not maintaining "a tradition of respect for intelligence as a social asset rather than a liability"? Why, this is our great tradition!

Has any member of our chapter stressed before the committee that "no matter how little the national taxes might amount to in terms of expense to individual members, they would not be worth it"?

Let him stand forth.

Has any man refused election to Phi Beta Kappa because of the added expense of our national fraternity connection?

Well, hardly!

We believe we have always followed the majority recommendations. We have kept our membership under fifty and for the sake of greater revenue have never been tempted to lower our standards. We maintain a "decent minimum standard of intellectual attainment." We practice no "racial or religious discrimination," although I must admit that names of English derivation are found but rarely on the rolls of some of our sister chapters. No man living can say that our members by their mode of life do not "discourage excessive week-ending and over-cutting," and certainly in our chapter no pressure is ever put on our members "to hold office or serve on committees," and when necessary we "protect the time and energy of brothers in scholastic difficulties."

Wherein have we failed? After much ex- tensive research I think I have found the answer in the majority report. We have not fulfilled our "maximum opportunity" by failing to promote "musical and dramatic interests in the fraternity"; we stubbornly insist on selecting from time to time a member who fails to reach "a minimum respectable standard in regard to character and personal habits/' and much as I hate to confess it, we have not entered into joint fraternity projects such as dances, ice sculpture and inter-fraternity athletic competitions. It is for these things that we are to be hung, drawn and quartered and deprived of our good name and reputation. Brothers in Phi Beta Kappa, I warn you that unless you fulfill your "maximum opportunity" as set forth in the majority report, the chapter of the brilliant Choate and of the godlike Daniel will cease to exist and even then, it may be too late, for I fear that the practice of contributing to a national organization, in some cases considered iniquitous, has doomed us all.

Picture if you will, in the future, a brother of the new local, the Midnight Owls, so-called successors to the Dartmouth chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, proudly displaying on his watch chain the appropriate emblem of a great white owl (in silver) with flashing eyes, grasping in his talons Dartmouth's New Shuffle Fraternity Constitution, on which appears the motto: "All That Is Good Must Be Destroyed." What a royal welcome he will receive by the fellowship of scholars still so unenlightened as to become members of the national fraternity of Phi Beta Kappa!

Down with the Silver Owl! Up with the Golden Key! Compare the pale and pusillanimous scintillation of the silver owl with the gay and gleaming glitter of the golden key. Shall we change the name of Phi Beta Kappa? Why, dearie me; of course not!

ØßK. 1910

30 Federal St.Boston, Mass.

Friends of E. A. Robinson

To the Editor The undersigned friends of the late Edwin Arlington Robinson are planning to collect and edit a volume of his letters and have made arrangements with The Macmillan Company for their publication. Anyone who has any letters which might have general interest, and who is willing to have use made of them in such a volume, or in the biography of Mr. Robinson which Mr. Hermann Hagedorn is writing, is urged to send them by registered mail to any member of the committee. The letters will be copied promptly, and the originals returned to their owners with a typed copy.

Mr. Hagedorn is making a collection of newspaper and other clippings concerning Mr. Robinson, which will be mounted and ultimately deposited, for the use of scholars, in the Widener Library of Harvard University. He would be grateful if anyone who has any significant clippings and is willing to part with them would send them to him by registered mail at 28 East 20th Street, New York.

HERMANN HAGEDORN, 28 East 20th Street, New York LEWIS M. ISAACS, 475 Fifth Avenue, New York Louis V. LEDOUX, .155 Sixth Avenue, New York PERCY MACKAYE, The Players, 16 GramercyPark, New York RIDGELY TORRENCE, Morton Street, New York

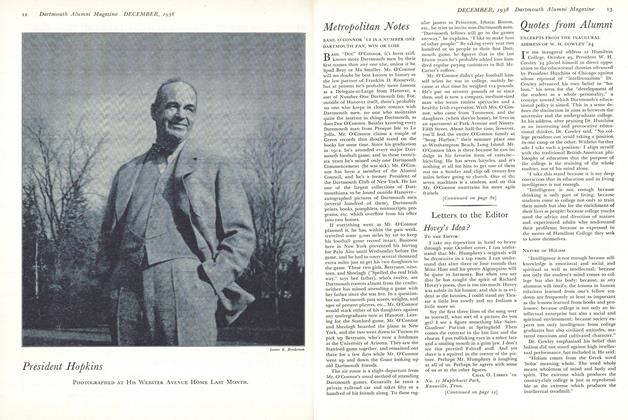

Websteriana

To the Editor At the request of Professor Neef I am glad to write the history of the pair of yellow decanters which I presented to the College this past Commencement.

These decanters were owned and used by Daniel Webster, class of 1801, in his Marshfield, Massachusetts, home. After his death they were presented by his son to John P. Healy, class of 1835, who studied law in Mr. Webster's office. When Mr. Healy died, they came to Charles F. Kittredge, class of 1863, who was associated in the practice of law with Mr. Healy.

Upon the death of Mr. Kittredge, his widow gave them to me when I was associated with Mr. Kittredge in the practice of law.

And now it gives me great pleasure to present these beautiful and historic decanters to Dartmouth College. Five years ago I presented to the College an office chair used by Daniel Webster when he practiced law in Boston.

My interest in Webster centers somewhat in the fact of relationship on my maternal side through the Eastman Family. There is a further interesting connection with the College on my maternal side from the fact that my great, great grandfather, John Young, married for his second wife Theodora Wheelock, sister of Eleazar Wheelock, founder of the College and its first President; by this marriage was born Tryphen, who married Eleazar Wheelock, son of the President by his second wife; and furthermore that I was graduated from the College in 1896. On my paternal side I had two great uncles graduate from the College and other more remote relatives.

Tremont Building,Boston, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

October 1936 By The Editor -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

October 1936 By Paul C. Belknap -

Article

ArticlePresident Reviews Social Changes

October 1936 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1886

October 1936 By Henry W. Thurston -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1936 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1936 By Albert I. Dickerson

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1938 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1967 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1967 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

FEBRUARY • 1988 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA DANGEROUS CHEW

NOVEMBER 1992 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorBuying Glamour in Paris

MARCH 1994