To WILLIAM EATON, Dartmouth class of 1790, it was given to enjoy a career whose romance has rarely been equalled. And yet history remembers his name only incidentally in relation to a half-forgotten phase of our early national existence. At least he should be remembered by Dartmouth men as a product of the same period which produced Daniel Webster and other great men in Dartmouth annals.

Bom at Woodstock, Connecticut, in 1764, William Eaton showed his restless craving for adventure by running away to join the American army at the age of sixteen. In spite of his youth he had been made a sergeant by the end of the war in 1783. But fighting was not his sole interest. His father was a schoolmaster, and William was much fonder of reading than farm work. In 1785 he was admitted to Dartmouth, but had to postpone starting his education until 1787 due to lack of funds. In May of that year he set out for Hanover on foot with his scanty belongings in a knapsack on his back. His entire stock of cash was one pistareen, a silver Spanish coin worth about twenty cents, and he counted on eking out this slim resource by the sale of some "notions" which he carried in his pack. When he got as far as Northfield, Massachusetts, he was broke and tired, and so dispirited that he sat down and cried. This was certainly not a heroic prelude to a colorful career, and he soon continued his journey to Hanover.

After passing the customary entrance exams Eaton settled down to Hanover life, which must have been much duller then than now. It was only a few days after his arrival that Dartmouth Hall was dedicated, and Eaton may have been present when the grandstand collapsed and injured the dignity of the sedate celebrities present on the occasion. To meet expenses Eaton taught a school during the long winter recess, as did many other students of that period. At this time he was a serious lad, and once considered entering the Christian ministry. In light of his subsequent career it is hard to imagine him as a preacher.

Eaton managed to complete his course in Dartmouth in three years, and received his degree in August, 1790. It is interesting to speculate whether he ever returned to Hanover as a loyal alumnus. No authentic record of such a visit exists.

After one more year of schoolteaching, Eaton obtained a captain's commission in the U. S. Army, and in this capacity participated in "Mad Anthony" Wayne's campaign against the Ohio Indians in 1794. In a spare interval between moments of dashing around the country Eaton found time to woo and win Mrs. Eliza Danielson, a young widow of Brimfield, Massachusetts. This village near Springfield was Eaton's nominal home for the rest of his life. For a man who was away from home as much as Eaton,* he was fairly lucky in the matter of offspring, being blessed with three girls and two boys.

Eaton retired from the army in 1797 after an unpleasantness with a superior and received an appointment as U. S. consul to Tunis from Timothy Pickering, at that time Secretary of State. Eaton remained a warm supporter of the Federalist statesman all his life. The Tunis consulate was a ticklish post, since the Bey of Tunis, in common with the rulers of Morocco, Algiers, and Tripoli, was only a high-class racketeer. The swift corsairs of these powers preyed on the shipping of all nations who bought their protection in the guise of commercial treaties. At one time or another the United States spent $2,000,000 trying to satisfy these pirates, and finally had to resort to force.

Eaton soon learned the ropes in Tunis. He secured a revision of the U. S. Treaty with Tunis, although he had to hand out bribes right and left to do it. He soon found that the demands of the Bey were no sooner satisfied than fresh payments were required to prevent depredations on American commerce. He realized that force was required to hold the Barbary states to their promises, and he became a leading advocate of an adequate American naval force in the Mediterranean.

WAR IN AFRICA

Meanwhile, the refusal of the United States to meet the demands of the neighboring state of Tripoli led to a declaration of war on the United States on May, 1801. Commodore Dale's squadron of three frigates and a schooner was sent to the Barbary coast, but although Dale was a vigorous commander, little could be done against the city of Tripoli itself, for it was strongly fortified. Now it happened that the ruler of Tripoli, Yusuf Bashaw, was a usurper, having dethroned his elder brother, Hamet, a few years before. Yusuf was a harsh ruler and the people were said to be on the point of revolt. The exiled Bashaw, Hamet, was living in Tunis, and Eaton conspired with him to lead an overland expedition against Tripoli, dethrone Yusuf, and maintain Hamet as the puppet of the United States. Hamet himself was a weak character, but Eaton had strength enough for two, and set about the difficult task of securing the support of the Washing authorities for his project.

It was up-hill going at best. Secretary of State Madison was indifferent, and the naval officers of the spot skeptical of the plan's feasibility. To make matters worse, Eaton was financially embarrassed, so in 1803 he gave up the consulate and returned to the United States. Here he had better luck and received an appointment as U. S. navy agent for the Barbary Powers and a small sum from the Navy Department. His instructions were ambiguous, and he was well aware that he could expect little support from the government unless he succeeded.

After Eaton's departure from Tunis, Hamet had been on the loose, and when Eaton returned was abetting a revolution against the Turks in Egypt. Eaton managed to persuade the Turks that it was better to have Hamet outside the country, so Hamet was allowed to meet Eaton near Alexandria. Together they recruited their force. Composed of the riffraff of Alexandria, nearly every European nationality was represented in addition to the Arabs who formed the bulk of this improvised army. It was not until March 8, 1805, that the march across the desert was started. The plan was to follow the seacoast to the Bay of Bomba, in Tripoli, where the land force was to be reenforced by some U. S. naval vessels. Then they were to capture the city of Derne, the most important place in the eastern part of the country, and proceed to the city of Tripoli.

The obstacles met and surmounted by Eaton on that trek of over 600 miles across the desert were more than enough to turn back any ordinary man. The camel drivers were continually demanding their pay; the Arabs were always on the point of desertion; food and water were frequently scarce; and worst of all Hamet proved to be so weak-kneed that there was no depending on him. Many times Eaton faced death as Arab fingers crooked over the triggers of long Arab rifles, but his courage never faltered. He brought his army through to Bomba. They were half-starved, but they got there. Then on April 25, 1805, Eaton led the charge of a handful of American marines and Greeks into Derne while the guns of the U. S. brig Argus boomed in the background, and Hamet placed his men so as to capture a maximum of booty. For the first and last time until 1919 the Stars and Stripes flew over an Old World Fortress! Eaton surely deserved the title of "general" conferred on him by Hamet.

The anti-climax was close at hand, however. Commodore Samuel Barron, in command of the fleet, was afraid Eaton had ex- ceeded his instructions (which was true) and withheld supplies for a further campaign against the city of Tripoli itself. Then, on June 3, a treaty was signed between Yusuf and the United States ending the war, and Eaton had to ship aboard the Constellation under cover of darkness to avoid lynching by the inhabitants of Derne, who had supported Hamet's cause so loyally.

The useful part of Eaton's life was now over. A heated controversy was waged as to the propriety of Barron's failure to support Eaton, and a Senate investigation condemned these orders most severely. Eaton was for a time a figure of national importance. Everywhere he went he received public banquets. The Massachusetts legislature voted him an extensive land grant in Maine. In 1807 he was elected to the legislature from his Brimfield home, but failed of reelection two years later. Accustomed to an exciting life, he could not stand the strain of civilized existence and began to drink heavily. He was addicted to gambling, and in this way managed to lose most of his real and personal property. He loved to talk of his exploits, and frequently gave way to mere bragging. He suffered a good deal from ill health during 1810 and died on June 1, 1811, in Brimfield, where he received a military burial.

Eaton was a man of action. He had about him a lack of tact and a forthright directness which served well at times but more frequently was a handicap. He had a hot temper, and on occasion gave it free rein, as when he horse-whipped a man on the streets of Tunis. Not a lady's man, he apparently found little difficulty in staying away from his wife for long periods, and he did not associate with other women, at least as far as the records go. He was absolutely without knowledge of physical fear, and he was a peerless leader of men. His patriotism was something to swear by. On the whole, it is impossible to avoid liking Eaton, even considering his faults. He was a true son of Dartmouth.

GENERAL WILLIAM EATON Adventurer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1936 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Olympic Skiers

February 1936 By Robert P. Fuller, '37 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleEdwin Brant Frost, Class of 1886

February 1936 By Arthur Fairbanks '86 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1936 By Martin J. Dyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1936 By L. W. Griswold

Article

-

Article

Article"DARTMOUTH BED" ESTABLISHED

May 1917 -

Article

ArticleCorporate Gifts to the College Totaled $111,200 During 1955

March 1956 -

Article

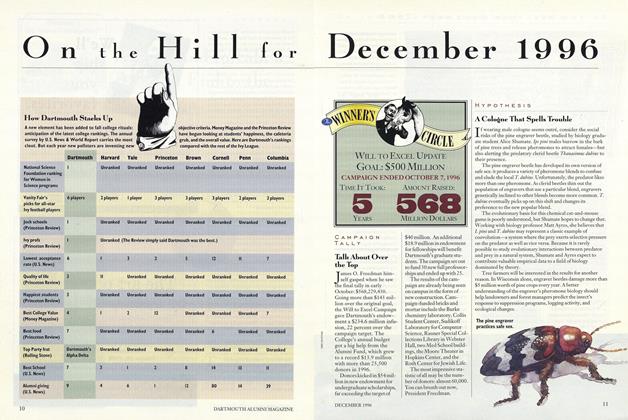

ArticleTalk About Over the Top

DECEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleDeciphering Proteins

Mar/Apr 2002 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

Nov/Dec 2009 -

Article

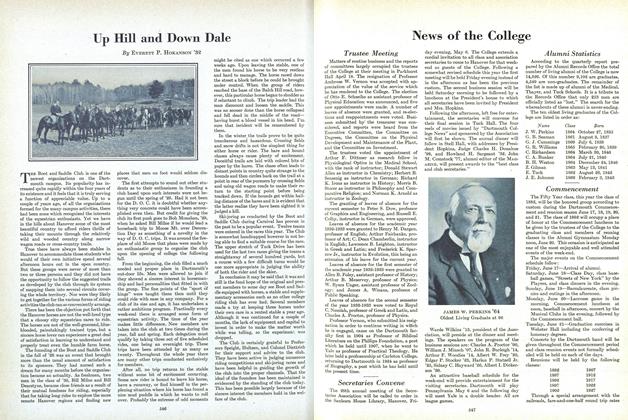

ArticleUp Hill and Down Dale

MAY 1932 By Everett P. Hokanson '32