An Appreciation of His Contributions to Astronomy and Humane Living

EDWIN BRANT FROST, b. July 14, 1866; d. May 14, 1935. A.B. Dartmouth 1886, A.M. 1889, D.Sc. 1911, D.Sc. University of Cambridge, England, 1912. Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1889, and a Vice President in 1912. Member, 1891, of the American Astronomical Society; and of the Astronomische Gesellschaft; 1908, National Academy of Sciences (Washington); 1909, American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia); 1913, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Boston); 1915, Washington Academy of Sciences. Foreign Associate or Honorary Member; 1908, Royal Astronomical Society (London); 1909, Societa degli Spettroscopisti Italian, Astronomical Society of Mexico, Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Russian Astronomical Society.

IN CHAPTER 23 of his Autobiography Dr. Frost of the class of 1886 gives a review of the progress of astronomy during the half century which ended when he wrote in 1933. In the preceding half century, he writes (p. 229) "the field of practical and theoretical astronomy had been well developed .... and valuable pioneer work had been done" with the spectrum of the sun. It remained for Frost and his contemporaries to apply the spectroscope to the study of the stars, as better telescopes and the development of the photographic method opened this new field for astrophysics.

Dartmouth had an honorable record in astronomy as a result of the work of Ira Young and his son, Charles A. Young, in the observatory, before the latter accepted a call to Princeton. After a few months' study with Professor Young at Princeton, young Frost was appointed instructor in physics and astronomy in the Chandler School and assistant in physics in Dartmouth College with the responsibility for the observatory, a post he held from September, 1887, till he left for study in Europe in June, 1890. A summer in Gottingen to learn German and a winter semester studying astronomy with Kohlransch at Strassburg preceded his appointment as a volunteer assistant at the Potsdam Astrophysical Observatory under Director Vogel. Here he won recognition in his chosen field and made many friends.

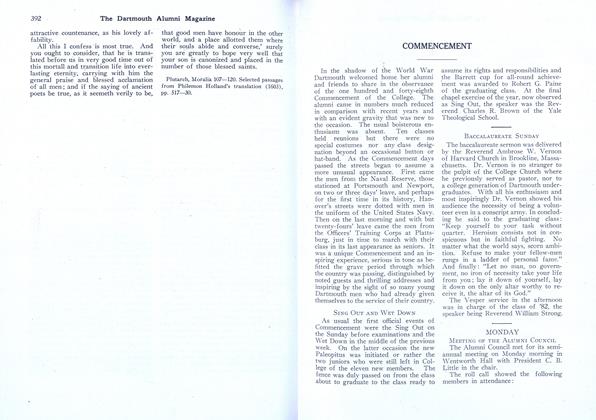

Returning to Dartmouth, Frost served as assistant professor, then profressor of astronomy from 1892 to 1898. He proved an inspiring teacher, lovingly remembered by his pupils in their later years. Nor was his work in physics neglected. It was in January, 1896, that cables gave fragmentary information of Rontgen's discovery that by the use of the X-ray, photographs could be taken through opaque matter. Frost immediately tested the vacuum tubes in the physical laboratory at Dartmouth to confirm the discovery. His brother, Dr. Gilman D. Frost, brought him a patient with a broken bone in the arm, and on February 3 he obtained the first X-ray photograph of a fractured bone made in America. (Science, February 14, 1896.)

A call to the professorship of astrophysics at the Yerkes Observatory of the University of Chicago offered such opportunities that it could not be refused, though for four years more he continued to teach astronomy at Dartmouth during the winter term. At Williams Bay he began what was to be his life work with the 40-inch refractor, the largest telescope of its type in the world, under the inspiring guidance of George E. Hale. In the absences of Mr. Hale he served as Acting Director, and in 1905 was appointed Director of the Observatory. In 1901 he assisted Mr. Hale in designing the Bruce spectrograph for spectroscopic study of the stars; the best type of micrometers were secured; and in 1904 a 10-inch refractor was erected with special lenses devised for photographing the stars. With the apparatus thus available it was possible to determine by the spectroscope not only the physical elements of the stars, but also—as the lines of the spectrum were shifted slightly when the star was moving the line of sight—the motion toward or from the observer. At the same time, by means of photographs, the lateral motion of stars could be discovered, and by a combination of both methods it was often possible to discover the mass of a star as well as the direction and speed of its motion. Photography also revealed immense numbers of stars not visible to the naked eye, and in many instances furnished the data for determining the distance of stars from our sun. "The result has been that our conception of the size of the universe has been in forty years magnified many thousand fold, perhaps a million fold." (Autobiography, p. 228.)

The work of the director of a large observatory is many fold. It includes administrative problems—to secure funds for the institution; to select and guide the work of members of the staff, some refatively permanent, and some staying only for a few months; to supervise the apparatus, improving the existing equipment and devising new instruments; and to entertain visiting astronomers from all over the world. That Dr. Frost was most successful in stimulating and training his staff is shown by the number of astronomers in different American observatories who had worked with him at the Yerkes Observatory: Director Frank Schlesinger, Yale; Director S. A. Mitchel, University of Virginia; Walter S. Adams '9B of the Mt. Wilson Observatory; Dr. Philip Fose of the Adler Planetarium; Professor John Poor '97, Dartmouth; Director C. P. Oliver, Flower Observatory, Philadelphia; Director Frank Jordon, Alleghany Observatory, Pittsburg; Director Otto Struve, Yerkes Observatory. It includes further his own astronomical work.

Frost's special field was the determination by the spectroscope of the radial velocity of so-called helium or early type stars, investigation which led him to the idea of an expanding universe, for the motion was ordinarily away from the earth in different directions. The method he developed is now being carried on by some 35 observers and records have been made of over 500 stars. Finally, in Frost's case it included the editorship of the Astrophysical Journal, founded by Mr. Hale, for some thirty years. In this Journal he himself published more than a hundred papers. Further, he edited seven quarto volumes of the Publications of the YerkesObservatory. One of his then assistants, Director Schlesinger of Yale, says of him as editor, "he is the best skeptic I know," with the result that the Journal could rarely be criticized for any oversight or error in its articles, and he speaks further of Frost's sensitiveness for language, as apparent both in his articles and in his editorial work.

Frost was gifted in every way for the profession he chose, except for his weak eyes. In 1915, after a strenuous night of observation, the sight of one eye began to fail and soon a detachment of the retina became apparent. A few years later a cataract in the other eye reduced his vision till shortly he became totally blind. To keep on with his work after becoming blind would hardly have been possible without the devoted care and constant assistance of his wife; with her assistance and with the aid of his trained observers he continued his investigations, his editorial work, and his direction of the Observatory until failing health obliged him to resign in 1932. The writer recalls a visit with him a year or two later, in which he spoke of making long mathematical calculations in his head after he had gone to bed at night. He told me how, as his eyesight failed, he had prepared to continue his work, learning to memorize his steps in unfamiliar places and to guide his walks near the Observatory by sounds and smells. His one regret was that he had not committed to memory the table of logarithms, as its use would have been so helpful in his calculations after sight was gone! All his friends pay tribute, not to any stoicism, but to the cheerful courage with which he met and to so large an extent overcame the severest blow that could come to an observing scientist. His home was always a centre for his associates, his neighbors, and his many friends in Chicago; these he met, not as a blind man, but with the humor and the intense personal interest in them which he had always shown.

No ACCOUNT OF him would be complete without some further reference to his personality, which can best be given in a few extracts from the funeral address of Dr. Edgar J. Goodspeed:

"Nothing marked him more than his keen personal interest in his fellowman. If he motored through old haunts in New England he must stop at every village to look up some old playmate of his boyhood whom he might not have seen for forty years. On his sixty-fifth birthday when hundreds of his friends came to see him at Williams Bay and the telegrams of congratulation literally overwhelmed the local telegraph office, no message moved him so much as the one from the train crew of the morning and afternoon train (from Chicago) signed by each man in it. ... . Children loved him and he delighted in them, and himself retained to the end of his life the heart of a boy.

"It was his unfailing interest in people which led him to write to young Otto Struve, who came of a famous line of Russian astronomers and whom the revolution had driven to Constantinople as a refugee .... so began the dramatic series of events that culminated ten years later in the appointment of Dr. Struve as his successor in the directorship of the Observatory.

"We shall always think of his interest in nature—the nature of the earth as well as of the stars, of his early measures to beautify the grounds about the Observatory .... and of his enthusiasm for his roses in which he became such an expert. Who of us can forget that table spread every day by Mrs. Frost with a hundred varieties of Dr. Frost's roses, each in its single vase? .... His interest in birds never left him. His skill in recognizing and imitating bird calls was a wonder to his friends and gave him great enjoyment.

"There was such a range to his interests; old friends, children, birds, flowers, insects, music, and the stars in their courses.

"Dr. Frost's religious interest was deep and active. He saw that we may gain a finer conception of the Creator by the study of His works. To stand with him on the steps of the Observatory and hear him utter in the simplest and most natural way his deep and broad religious convictions was an experience never to be forgotten. To him, indeed, the heavens were telling the Glory of God.

"Certainly the world is immensely richer because Edwin Frost has passed through it, and we are all of us a little wiser and a little braver and—dare I say?—a little gayer, because he passed our way."

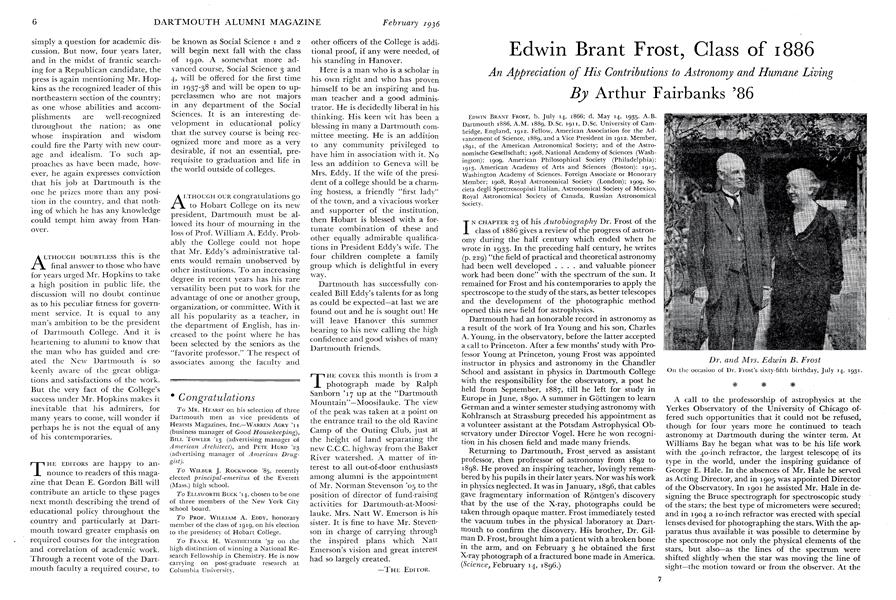

Dr. and Mrs. Edwin B. Frost On the occasion of Dr. Frost's sixty-fifth birthday, July 14, 1931.

An Historical Moment for American Medicine The first experiment in X-ray photography in America when Prof. Edwin B. Frost '86, left, aided by his brother, Dr. Gilman D. Frost '86, right, made America's first picture of a broken arm. The place: Physics Laboratory in Reed Hall. The time: January 20, 1896. Patient: Edward McCarthy. Mrs. Gilman Frost was also present at the historic occasion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1936 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Olympic Skiers

February 1936 By Robert P. Fuller, '37 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1936 By Martin J. Dyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1936 By L. W. Griswold -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

February 1936 By William L. Krieg '35