By Leonard W. Doob '29. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1935. Pp. 424.

This book by a recent Dartmouth graduate and more recent Dartmouth instructor has an unusual breadth of appeal. In a time when the lives of many groups are being systematically influenced by centralized propaganda and when other groups are assailed from many sides, a knowledge of the methods and intentions of propagandists becomes most desirable. As Dr. Doob suggets, propaganda is bound to exist, but the very recognition of propaganda as such may lessen the influence of certain of its forms. The present book does much to aid in this recognition, both by presenting examples and by suggesting a series of "principles of propaganda" for their understanding. These concise principles should interest the general reader by their content and the social scientist by their form as well. (Though not intended for him, they might also well serve the interests of the man with a mouse-trap or a Utopia to sell!)

The author has been in close contact with propagandists in a variety of fields, and describes in highly readable fashion the activities of such divergent groups as the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the Lord's Day Alliance, the Communist Party, the Nazi Party, and the munitions makers. He also makes a survey of newspapers, radio, movies, and other vehicles of propaganda.

Unlike some authors on the subject, however, Dr. Doob does much more than report cases for their temporary interest. He argues that "an instance of propaganda must be viewed not as an isolated, curious, or revolting sample of human perversity, but as a function of a particular kind of society." Keeping this social perspective, he makes an analysis of the psychological processes involved which is a distinct contribution to the literature of social psychology. An important part of his task is the clarification of basic concepts. Whenever possible he conforms to general usage, but where usage is confused and conflicting he does not hesitate to adjust definitions to make a consistent set of concepts, which he then employs in his "principles."

This systematic organization is perhaps the most valuable feature of the book. While some writers may object to minor matters of emphasis, all should admire the straightforward and clearly thought out manner in which the system is developed. Social psychology needs more such writing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1936 -

Article

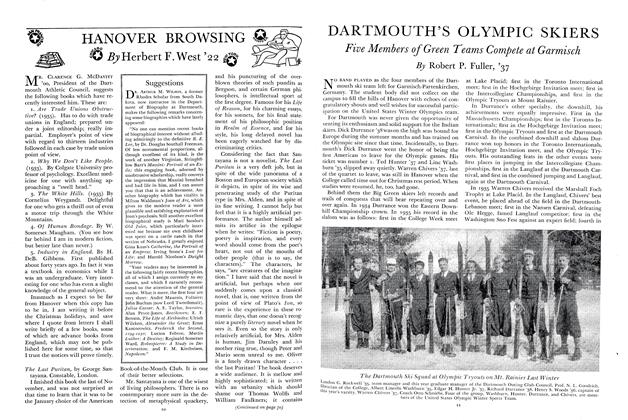

ArticleDartmouth's Olympic Skiers

February 1936 By Robert P. Fuller, '37 -

Class Notes

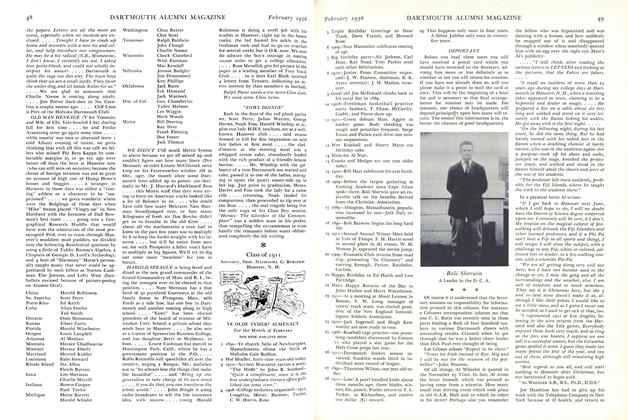

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

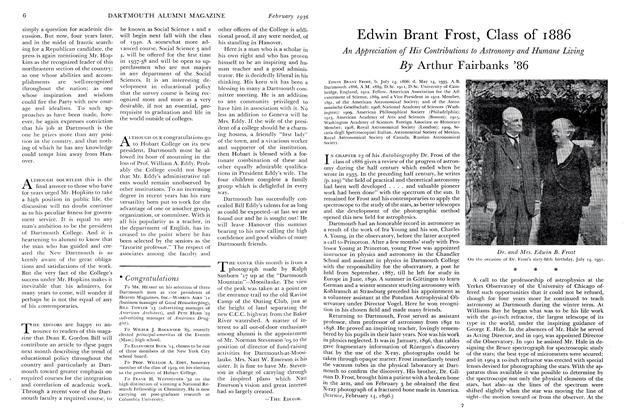

ArticleEdwin Brant Frost, Class of 1886

February 1936 By Arthur Fairbanks '86 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1936 By Martin J. Dyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1936 By L. W. Griswold

Henry S. Odbert '30

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

November 1944 -

Books

BooksProfessor Gordon Ferrie Hull Jr. '37

February 1946 -

Books

BooksHUCK JONES: A Novel of a Pre-Teenage Boy.

March 1958 By C.N. ALLEN '24 -

Books

BooksSOCIAL PROBLEMS ON THE HOME FRONT,

April 1948 By GEORGE F. THEIUAULT '33. -

Books

BooksTHE LAND OF RUMBELOW.

JANUARY 1964 By R. J. B. JR. -

Books

BooksWHAT IS MAN

December 1952 By T. S. K. Scott-Craig