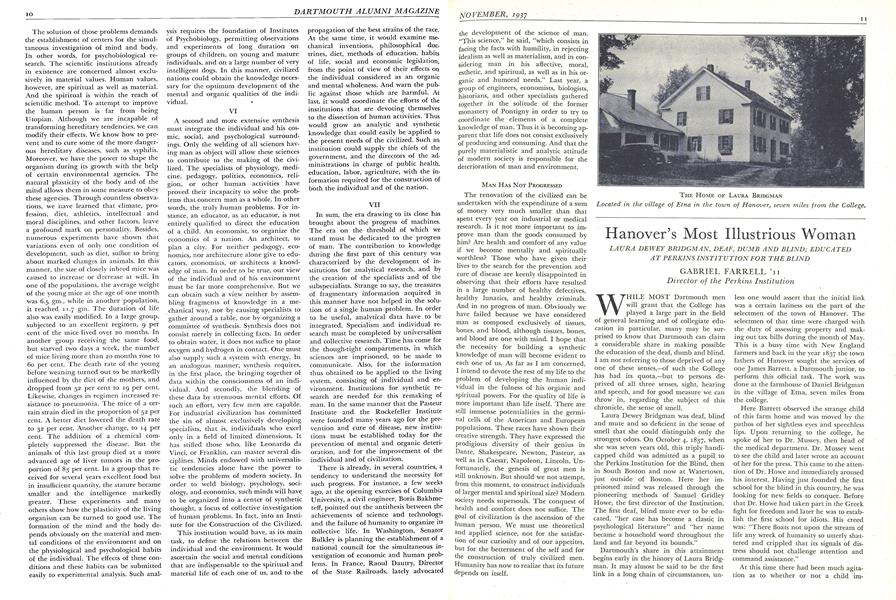

LAURA DEWEY BRIDGMAN, DEAF, DUMB AND BLIND; EDUCATEDAT PERKINS INSTITUTION FOR THE BLIND

WHILE MOST Dartmouth men will grant that the College has played a large part in the field of general learning and of collegiate education in particular, many may be surprised to know that Dartmouth can claim a considerable share in making possible the education of the deaf, dumb and blind. I am not referring to those deprived of any one of these senses,—of such the College has had its quota,—but to persons deprived of all three senses, sight, hearing and speech, and for good measure we can throw in, regarding the subject of this chronicle, the sense of smell.

Laura Dewey Bridgman was deaf, blind and mute and so deficient in the sense of smell that she could distinguish only the strongest odors. On October 4, 1837, when she was seven years old, this triply handicapped child was admitted as a pupil to the Perkins Institution for the Blind, then in South Boston and now at Watertown, just outside of Boston. Here her imprisoned mind was released through the pioneering methods of Samuel Gridley Howe, the first director of the Institution. The first deaf, blind mute ever to be educated, "her case has become a classic in psychological literature" and "her name became a household word throughout the land and far beyond its bounds."

Dartmouth's share in this attainment begins early in the history of Laura Bridgman. It may almost be said to be the first link in a long chain of circumstances, unless one would assert that the initial link was a certain laziness on the part of the selectmen of the town of Hanover. The selectmen of that time were charged with the duty of assessing property and making out tax bills during the month of May. This is a busy time with New England farmers and back in the year 1837 the town fathers of Hanover sought the services of one James Barrett, a Dartmouth junior, to perform this official task. The work was done at the farmhouse of Daniel Bridgman in the village of Etna, seven miles from the college.

Here Barrett observed the strange child of this farm home and was moved by the pathos of her sightless eyes and speechless lips. Upon returning to the college, he spoke of her to Dr. Mussey, then head of the medical department. Dr. Mussey went to see the child and later wrote an account of her for the press. This came to the attention of Dr. Howe and immediately aroused his interest. Having just founded the first school for the blind in this country, he was looking for new fields to conquer. Before that Dr. Howe had taken part in the Greek fight for freedom and later he was to establish the first school for idiots. His creed was: "There floats not upon the stream of life any wreck of humanity so utterly shattered and crippled that its signals of distress should not challenge attention and command assistance."

At this time there had been much agitation as to whether or not a child imprisoned in the dark silence could be released. American educators of the deaf were concerned with the plight of Julia Brace, a pupil at the American Asylum for the Deaf at Hartford, Connecticut, and had given up in despair, although Dr. Howe, who had been watching the case, felt that it should not be abandoned. At the same time certain English scientists, Sir Dugald Stewart, Sir Astley Cooper and others had declared, in connection with one James Mitchell, a deaf-blind boy in England, that nothing could be done to overcome the double loss of sight and hearing. The finality of these decrees only whetted the desire of the director of Perkins to try his hand when he heard of the little deaf-blind girl in New Hampshire.

A DISTINGUISHED COMPANY

In June, 1837, Dr. Howe went to Hanover to secure his prize. A party of five made the journey by stage coach. One was young Samuel Eliot who later wrote to a daughter of Dr. Howe: "Your father was one of a party of four (or five, including myself, then 15 years old) as far as Hanover, N. H. The others were Rufus Choate, G. S. Hillard and Longfellow, at whose invitation I was allowed to go. Choate was to join his family at Hanover and stay there, the others were to travel farther to the White Mts.; but Hanover was the first point with your father, on Laura's account, and with Hillard, because of an oration he was to deliver before a Dartmouth College literary*society at Commencement."

The name Rufus Choate needs no introduction to Dartmouth readers and all will understand that "Longfellow" is none other than Henry Wadsworth, who, that very year, had come from Bowdoin to Harvard to take the chair of George Ticknor, one of Dartmouth's most illustrious graduates. I am ready to confess that the name of Hillard, the commencement orator, meant nothing to me. However, reading Van Wyck Brooks' Flowering of New England, his distinction has been revealed and the reason for his inclusion in the group has become clear. George S. Hillard, Harvard graduate, was the law partner of Charles Sumner, one of Howe's closest friends, and was himself an author and one of the galaxy of bright stars of that brilliant day.

It is recorded that Howe "had the patience to hear his friend's oration on the first day's stay at Hanover. On the second he easily tore himself from the commencement exercises and drove to the Bridgman home in quest of his prize." In the "spare parlor" of the old farmhouse, Dr. Howe met Laura Bridgman for the first time. He presented her with a silver pencil case but she was so terrified that she let the gift fall and never found it again. As the author of the Life of Laura Bridgman has written; "If any prophet had foretold what a future lay before that little trembling child standing alone in silent darkness, linked to her kind only by the bond of a common humanity, who would have given him credence!"

Although the story of Laura Bridgman is, or ought to be, familiar to all, some may be interested in knowing how Dr. Howe was able to reach beyond the barriers of blindness and deafness. As he appraised the situation he realized that he must choose one of two ways. He could build on the foundation already laid in her own home, and generally used among the deaf, and teach her the language of signs. The alternative was, in his own words, "to give her a knowledge of letters, by the combination of which she might express her idea of the existence, and the mode and condition of anything. The former would have been easy but very ineffectual; the latter seemed very difficult, but if accomplished, very effectual. I determined, therefore, to try the latter."

Three steps were involved in this process. Taking common objects of daily use,key, spoon and book, Dr. Howe attached to them labels bearing their names in a raised type which he had invented for the blind. The child was urged to feel the objects and the words designating them until she could associate the right name with the object. The second, step was to separate names and objects and given an object the pupil was taught to select the proper label. The third step was to cut the words into letters and have the child select the letters that made up the name of the object. It is interesting to observe that words were used before letters, antedating by some ten years the introduction of the word method by Mrs. Horace Mann and her sister, Miss Elizabeth Peabody. As friends of Dr. Howe they probably got the idea from him.

When Laura Bridgman was twenty- three, it was thought advisable for her to return to her home in Etna. After a few months it became apparent that she missed the activity and the associations of the Institution and began to pine for them. She lost interest in life, her appetite failed and it was soon evident that she was going into a decline. Miss Paddock of the Institution staff was sent to Etna and when Laura was told that she would be taken to the Institution her first inquiry was, "When do we start?" This practical person replied, "As soon as you can eat an egg." The very next morning the egg was eaten and in several days the start was made. At Lebanon Laura was placed "on a sofa in a saloon car" and it was so cold that passengers took turns in putting hot bricks on her hands and feet. Among those assisting in this was the president of Dartmouth College.

INFLUENCE OF DICKENS

For the rest of her life Laura lived at the Institution, the center of unceasing interest and the inspiration of other handicapped pupils. In her fifty-ninth year she passed away and her body was borne back to Hanover and now rests in a sylvan dale not far from the house of her birth. More Dartmouth men ought to know and visit these shrines. While in College I knew of her home in Etna, now owned by Mr. and Mrs. W. D. Paine, but only last summer did I discover the house of her birth and visit her last resting place. Leaving Etna on the road which turns right just before the brick church and pressing up the hill a mile or two, one turns left near a great pine. On the hill beyond is a little white farmhouse, now owned by the Danas, where Laura Bridgman's parents were married and she was born. At the foot of the hill to the right one glimpses a white gate, held closed when we were there by a birch log. Entering one finds the tomb stone at the left, marking the graves of the Bridgman family and duly inscribed with Laura's history.

One incident in the life of Laura Bridgman must not be passed by, both because of its historic interest and of its helpful consequences. Charles Dickens came to America in 184 a and when he visited Boston he spent most of his time at Perkins Institution. So absorbed was he in the deaf, blind child that, as a teacher reported, he "did not deign to notice anything or anybody except Laura." The extent of his interest may be measured by the fact that in his American Notes, Dickens devoted fourteen of thirty pages covering Boston to the account of the education of Laura Bridgman. Publication of her story in such a widely read volume made Laura a world character and was the basis of the recent claim that Charles Dickens was Perkins' first publicity agent.

The most important consequence of the relating of this story took place in an Alabama home some forty years later. The reading of Charles Dickens' AmericanNotes forged another link in the chain of events which make up the chronicle of work for the deaf-blind. In this Alabama home there was a little girl who was deaf, blind and mute. This was Helen Keller, then six years old. Filled with hope by what had been done for Laura Bridgman, the Kellers got in touch with Michael Anagnos, the second director of Perkins Institution. Soon arrangements were completed for Anne Sullivan, later Mrs. Macy, to become Helen's teacher. The story of the interwoyen lives of these two women is too well known to bear repeating but it is interesting to see how one event leads to another and how far reaching the printed word may be.

A NATIONAL CENTER NEEDED

In the century that has ensued since Laura Bridgman left Hanover, Perkins Institution has had about a score of deafblind pupils. Few have been as well known as the two already mentioned but all have been links in the chain of progress in this special field of education. In 1931 a department with specialized and enlarged facilities was formed to receive several pupils at a time and now there are ten totally deaf and blind children in residence and several who are partially handicapped in both senses. Plans are now in the process of development for the establishment at Perkins of a National Center for the deaf-blind which will give leadership to all work in this field.

The work now in process differs from that of former days in that our children are taught articulate speech from the beginning and are not allowed to use the sign language or manual alphabet. We have recently demonstrated that children who come to us mute, can be taught to speak and to understand speech" through vibration. With the normal avenues of communication opened in this way, our deaf-blind pupils can pursue regular school work, with the guidance of a special teacher. Hearing is through the finger tips which are placed on the throat of a person speaking in such a way that the vibrations of the muscles can be felt. Word meaning has to be built into the varying vibrations and the fingers taught to understand them. The initial work under the modern program is through commands rather than with objects as was the way devised by Dr. Howe. The fingers of a new child are placed in position on the teacher's throat and as she gives the command "Bow!" she pushes the child's body into a bowing position. This is repeated many times daily, sometimes for weeks, until the muscular action of bowing is associated with the vibrations felt when the word is uttered. When the first command is mastered, others follow more rapidly. It is, nevertheless, a difficult task but the method works as can be demonstrated by several children who can talk to any visitor and understand what is said to them through their fingers. Having proved what we can do for triply handicapped children it is now our desire to have the means to reach out and help all children living in the dark silence. To the extent that this work falls under my direction as the fourth director of Perkins, it can be said that Dartmouth is still sharing in the education of the deaf, blind and mute. At any rate I have a feeling that many Dartmouth men will be interested to know the chronicle of events that have followed that October day one hundred years ago when Laura Bridgman left her home to become Hanover's most illustrious woman.

THE HOME OF LAURA BRIDGMAN Located in the village of Etna in the town of Hanover, seven miles from the College.

THE GRAVESTONEMarking resting place of Laura Bridgmanin the old family burial ground in Etna.

Director of the Perkins Institution

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Making of Civilized Men

November 1937 By ALEXIS CARREL -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

November 1937 By THE EDITOR. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

November 1937 By Edwrd Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

November 1937 By Edward B. Marls Jr -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1928

November 1937 By Osmun Skinner -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Politics

November 1937 By HAROLD J. TOBIN '17

Article

-

Article

ArticleFrancis T. Fenn '37 Heads General Alumni Association

July 1961 -

Article

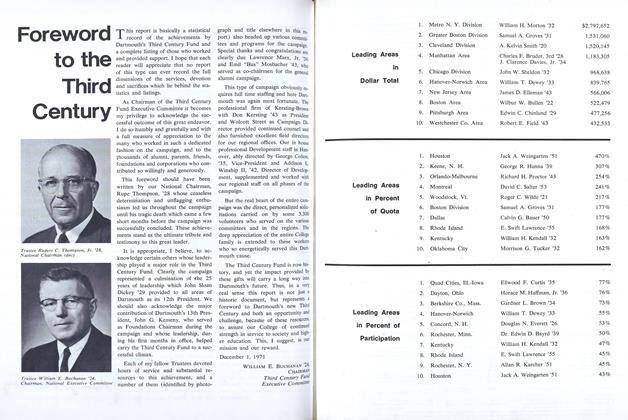

ArticleLeading Areas in Percent of Participation

DECEMBER 1971 -

Article

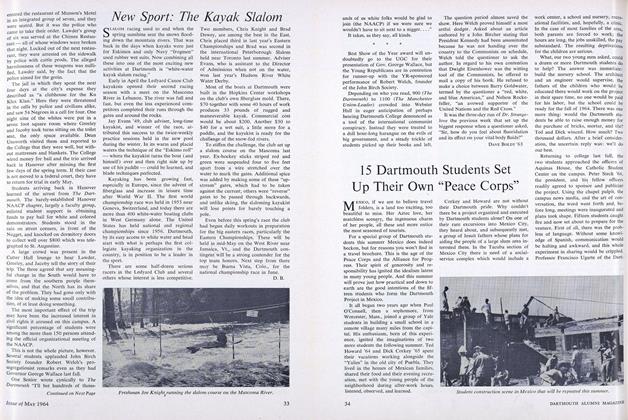

ArticleNew Sport: The Kayak Slalom

MAY 1964 By D. B. -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

JULY 1969 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleViet Nam: Problem of Power and Moral Purpose

JULY 1965 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

ArticleMR. QUINT DEFENDS "STORY OF DARTMOUTH"

February, 1915 By WILDER DWIGHT QUINT '87