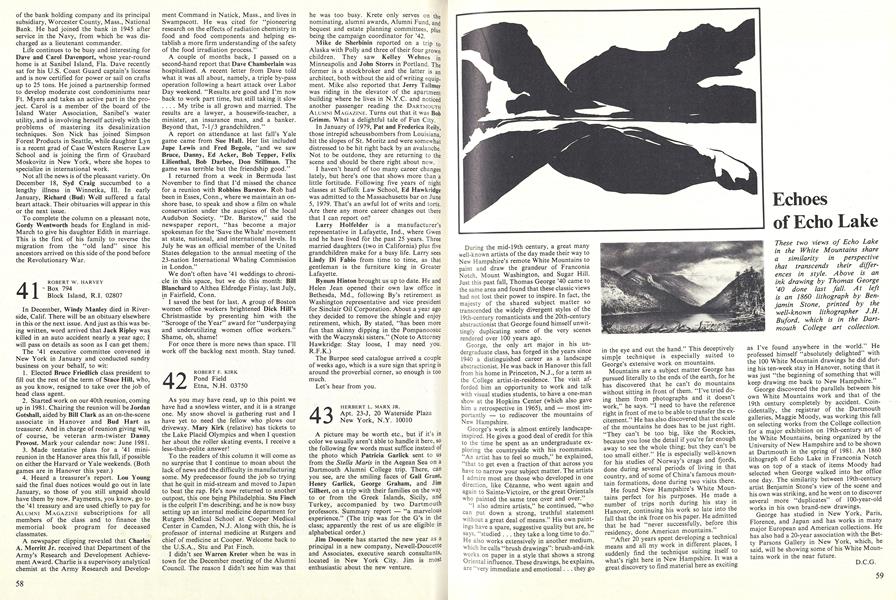

These two views of Echo Lakein the White Mountains sharea similarity in perspectivethat transcends their differences in style. Above is anink drawing by Thomas George'40 done last fall. At leftis an 1860 lithograph by Benjamin Stone, printed by thewell-known lithographer J.H.Buford, which is in the Dartmouth College art collection.

During the mid-19th century, a great many well-known artists of the day made their way to New Hampshire's remote White Mountains to paint and draw the grandeur of Franconia Notch, Mount Washington, and Sugar Hill. Just this past fall, Thomas George '40 came to the same area and found that these classic views had not lost their power to inspire. In fact, the majesty of the shared subject matter so transcended the widely divergent styles of the 19th-century romanticists and the 20th-century abstractionist that George found himself unwittingly duplicating some of the very scenes rendered over 100 years ago.

George, the only art major in his undergraduate class, has forged in the years since 1940 a distinguished career as a landscape abstractionist. He was back in Hanover this fall from his home in Princeton, N.J., for a term as the College artist-in-residence. The visit afforded him an opportunity to work and talk with visual studies students, to have a one-man show at the Hopkins Center (which also gave him a retrospective in 1965), and - most importantly - to rediscover the mountains of New Hampshire.

George's work is almost entirely landscapeinspired. He gives a good deal of credit for this to the time he spent as an undergraduate exploring the countryside with his roommates. "An artist has to feel so much," he explained, "that to get even a fraction of that across you have to narrow your subject matter. The artists 1 admire most are those who developed in one direction, like Cezanne, who went again and again to Sainte-Victoire, or the great Orientals who painted the same tree over and over."

"I also admire artists," he continued, "who can put down a strong, truthful statement without a great deal of means." His own paintings have a spare, suggestive quality but are, he says, "studied . . . they take a long time to do." He also works extensively in another medium, which he calls "brush drawings": brush-and-ink works on paper in a style that shows a strong Oriental influence. These drawings, he explains, are "very immediate and emotional. . . they go in the eye and out the hand. ' This deceptively simple technique is especially suited to George's extensive work on mountains.

Mountains are a subject matter George has pursued literally to the ends of the earth, for he has discovered that he can't do mountains without sitting in front of them. "I've tried doing them from photographs and it doesn't work," he says. "I need to have the reference right in front of me to be able to transfer the excitement." He has also discovered that the scale of the mountains he does has to be just right. "They can't be too big, like the Rockies, because you lose the detail if you re far enough away to see the whole thing; but they can't be too small either." He is especially well-known for his studies of Norway's crags and fjords, done during several periods of living in that country, and of some of China's famous mountain formations, done during two visits there.

He found New Hampshire's White Mountains perfect for his purposes. He made a number of trips north during his stay in Hanover, continuing his work so late into the fall that the ink froze on his paper. He admitted that he had "never successfully, before this residency, done American mountains.

"After 20 years spent developing a technical means and all my work in different places, I suddenly find the technique suiting itself to what's right here in New Hampshire. It was a great discovery to find material here as exciting as I've found anywhere in the world." He professed himself "absolutely delighted" with the 100 White Mountain drawings he did during his ten-week stay in Hanover, noting that it was just "the beginning of something that will keep drawing me back to New Hampshire."

George discovered the parallels between his own White Mountains work and that of the 19th century completely by accident. Coincidentally, the registrar of the Dartmouth galleries, Maggie Moody, was working this fall on selecting works from the College collection for a major exhibition on 19th-century art of the White Mountains, being organized by the University of New Hampshire and to be shown at Dartmouth in the spring of 1981. An 1860 lithograph of Echo Lake in Franconia Notch was on top of a stack of items Moody had selected when George walked into her office one day. The similarity between 19th-century artist Benjamin Stone's view of the scene and his own was striking, and he went on to discover several more "duplicates" of 100-year-old works in his own brand-new drawings.

George has studied in New York, Paris, Florence, and Japan and has works in many major European and American collections. He has also had a 20-year association with the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, which, he said, will be showing some of his White Mountains work in the near future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

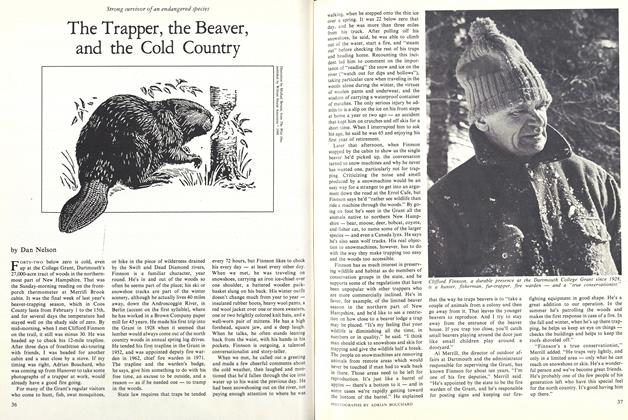

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

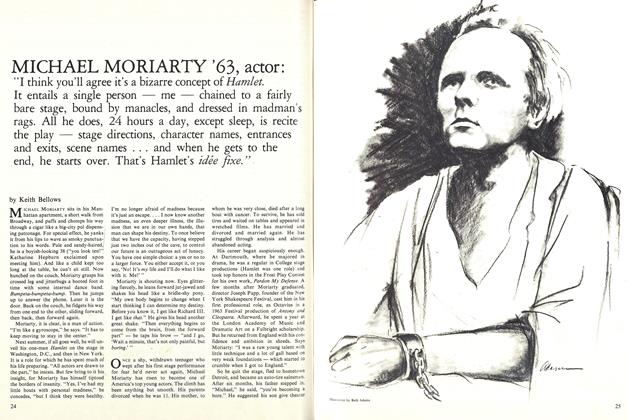

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

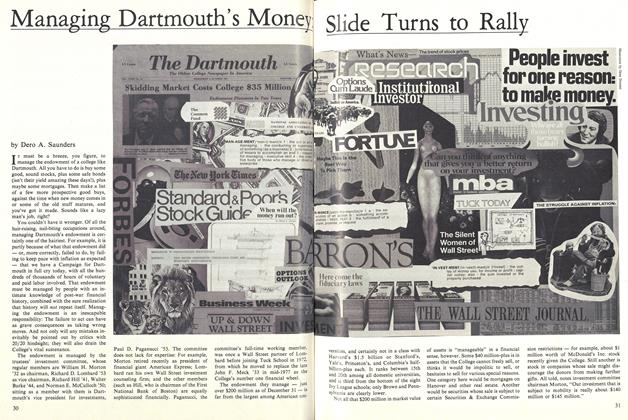

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

D.C.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Sad Necessity of Curing Football

MAY 1927 -

Article

ArticleA Winner by Six Degrees

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleInstitutional Ethics

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleMini Mania

Mar/Apr 2006 By Allison Caffvey '06 -

Article

ArticleSwimming

January 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22