AS A DARTMOUTH graduate, I have always been interested in the visits IJL of famous authors to our college campus, whether is was Oliver Wendell Holmes as Professor of Anatomy, Walt Whitman as Commencement Poet, Matthew Arnold as lecturer, or even such a casual Commencement visitor as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in July, 1837.

Although the poet Longfellow attended Bowdoin College in his native Maine, he came under Dartmouth influences at an early age when as a boy of ten years he entered the Portland Academy of which Bezaleel Cushman (Dartmouth, 1811), was superintendent and preceptor from 1815-1841. Of his youthful pupil, Preceptor Cushman wrote:

"He has during the week distinguished himself by his good deportment—Monday morning's lesson and occasional levity excepted."

How eagerly we should enjoy reading about these minor disciplinary infractions as judged by this Dartmouth teacher's standards. The following testimonial, however, indicates that in him Longfellow had a firm counsellor and friend:

"In all the relations of life he has ever sustained a most irreproachable and pure character. Hence he has always had the highest reputation for integrity, benevolence, and a long list of Christian virtues. Engaged as he has been for nearly a third of a century in the most important and responsible avocation of a teacher of youth, no great opportunities have been presented for popular notoriety. And his extreme modesty has kept him aloof from those associations of men which call the attention of the community or bring public approbation. But the good seed which he has planted in the minds and hearts of many young men who have been his pupils has produced fruit 'a hundred fold.' And many who are now occupying the highest positions in the several professions, in politics or in literature, can date to his teaching no inconsiderable part of their future success in life."

Longfellow's father, Stephen Longfellow, a graduate of Harvard, class of 1774, was a prominent lawyer in the city of Portland, onetime representative to Washington, and a trustee of Bowdoin; hence it was but natural that his sons should attend that institution so near the city of their birth. Henry and his brother Samuel spent their first year studying at home and entered upon their Bowdoin sophomore studies in the autumn of 1822.

Bowdoin was then under the presidency of William Allen, a graduate of Harvard College—a minister, lexicographer, author, librarian, and educator—who had entered the Wheelock Succession in a most direct and practical way by marrying for his first wife on January 28, 1813, Maria Melleville Wheelock, the only daughter of President John Wheelock of Dartmouth College.

Previous to his Bowdoin presidency, Mr. Allen (who was a prouounced Democrat and a firm believer in the close union between college and state), became a natural choice for a place on the Dartmouth University Faculty at the time when the New Hampshire Legislature altered Dartmouth's charter and attempted to reorganize the institution.

DIRECTED AFFAIRS OF "UNIVERSITY"

Two years of litigation followed between the College and the University (1817-1819) at the time when Mr. Allen carried on the affairs of the "University" until it went out of existence as the result of the United States Supreme Court decision. In December, 1819. he was chosen President of Bowdoin College where he remained until his resignation in 1839.

Thus the youthful and impressionable Longfellow studied under the man who was the son-in-law of John Wheelock, the grandson-in-law of Eleazar Wheelock, and who served for two years as president of one section of Dartmouth College. Al- though we know little about his wife Maria, she was undoubtedly familiar with her father's and grandfather's policies in the government of Dartmouth, and in some measure at least passed the substance of them on to her husband.

In Samuel Longfellow's Life and Lettersof Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, we find one chapter devoted to "College Years." In this chapter the future poet and professor seems content with the presidential policies and nowhere makes any comment concerning the Administration. In one letter only does he reveal his feeling of revolt against the type of religious instruction held at Bowdoin—probably a reflection of President Allen's policies:

To His MOTHER

"December 25, 1823.

"It has been a great day with us here today. I do not refer to the celebration of Christmas. But the Consociation of ministers met at this place today. They have exercises of a religious and publick [sic] kind both forenoon and afternoon, and I might add morning and evening. I have been so much of a heretick [sic] as to be audacious enough to shut my eyes against this clear and shining light and remain all day at home. I cannot find anybody who was present that remembers the text of the sermon. So much for going to meeting out of mere curiosity!"

Graduation from Bowdoin, graduate study at Harvard, marriage, trips to Europe for pleasure and study, widowerhood, professorship at Harvard, remarriage, parenthood, and thirteen years were to follow before Dartmouth again drew the attention of Longfellow; and even then he was not on the list of honored Commencement speakers!

In the summer vacation of 1837, the poet took a trip to the White Mountains in the company of his friend George S. Hillard, American author, lawyer, and politician, who was to give an oration en route at Dartmouth College. Mr. Rufus Choate (Dartmouth, 1819), and also Dr. Samuel G. Howe, husband of Julia Ward Howe, were the other members of this party. In a letter dated July 25, 1837, Longfellow wrote to his father:

"We have safely reached this place on our way to the White Mountains; and here we remain for two days. This afternoon, Mr. Hillard delivers his Oration; and tomorrow is Commencement with thirty-five orations. If we survive this, we shall start in the evening for Littleton, by way of Haverhill; thence go to Franconia, and then through the Notch to Portland.

"Last evening I was at Dr. Mussey's where there was music and lemonade. I dined with him today, though on his assurance that at Commencement time they live not on bread alone."

DR. MUSSEY A DIETETIC CRANK

The reference to the doctor is amusing, inasmuch as Reuben Dimond Mussey (Dartmouth, 1803), was then considered somewhat of a crank on diet: all alcoholic beverages, tobacco, and meat were off his list; and in one case he prescribed a vegetable diet as a cure for tuberculosis.

As Dr. Mussey and Longfellow were on the Bowdoin Faculty at the same time, the doctor furnished Longfellow with still another Dartmouth contact, and naturally was host to him on his visit in Hanover.

To continue with the aforementioned letter, Longfellow writes—

"Hanover stands on the broad level summit of a hill,—surrounded by a valley, like the fosse of a citadel; and beyond this are pleasant green hills, forming an amphitheatre to the north, east, and west, and opening southward upon the plain..... "26th. Hillard's Oration yesterday afternoon

was brilliant and very highly finished. It has gained him great applause, and in truth does him infinite credit.of the thirty-five Orations, I have heard twenty-five this forenoon. A greater part of the afternoon I have passed on the balcony of the hotel, looking at the great crowd assembled around the carts of the pedlers who are selling their wares at auction. This evening I take tea with President Lord. Last evening I was at Mr. Olcott's. He was a member of the Hartford Convention. Do you remember him? A quiet, pleasant man."

Although Professor Longfellow was not an active participant in the official Commencement Program, his letter proves that he was in illustrious company and that through his Harvard College connections as well as because of his Bowdoin-Dartmouth associations, he received definite and courteous recognition.

A brief account of the 1837 Dartmouth Commencement, printed in the Windsor,Vermont, Chronicle under date of August 2, 1837, supplements Longfellow's letter to his father. In this article we read that on Tuesday, George S. Hillard of Boston delivered an oration before the Literary Societies "which was said to have been very able and eloquent."

On Wednesday, the following departments shared the honors, each department with nine orations: Classical, Mathematical and Physical, Rhetorical, and Moral and Intellectual Philosophy, making in all thirty-six speeches in one brief day. The President conferred the graduate and undergraduate degrees and delivered the Baccalaureate Address. Incidentally the Doctor of Divinity Degree was conferred on President Hopkins of Williams College.

ORATORS MAINLY NEW ENGLANDERS

The locale of these orators in the graduating class was distinctively New England: eighteen from New Hampshire, nine from Vermont, four from Maine, four from Massachusetts, and one from far off Charlottesville, Virginia.

Notice the subjects of some of these orations which Longfellow managed "to survive": from the Classical Department: "The Credibility of Early History"; "The Return of Cicero from Exile." From the Mathematical and Physical Department: 'The Harmony of Science and Revelation"; "Mexican Antiquities." From the Rhetorical Department: "Indian Eloquence"; "The Uncertainty of Literary Judgments." From the Department of Moral and Intellectual Philosophy: "Equality in a Free Government."

No further entries concerning Dartmouth or the White Mountains occur in the poet's published Journals and Correspondence; and in his collected poems is only one which might have been inspired by his vacation trip with the Dartmouth Interlude—"Mad River in the White Mountains": What secret trouble stirs thy breast?Why all this fret and flurry?Dost thou not know that what is bestIn this too restless world is restFrom over-work and worry?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleYANKEE INGENUITY HAS NOT ENTIRELY DISAPPEARED, A TALE OF "AUSTIN'S ANTS" AND THEIR ANTICS

March 1937 By JOHN HURD JR. '21 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1937 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1926

March 1937 By Charles S. Bishop -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

March 1937 By Richard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

March 1937 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

JASON ALMUS RUSSELL '20

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE NEW DARTMOUTH HALL

FEBRUARY 1906 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

June 1941 -

Article

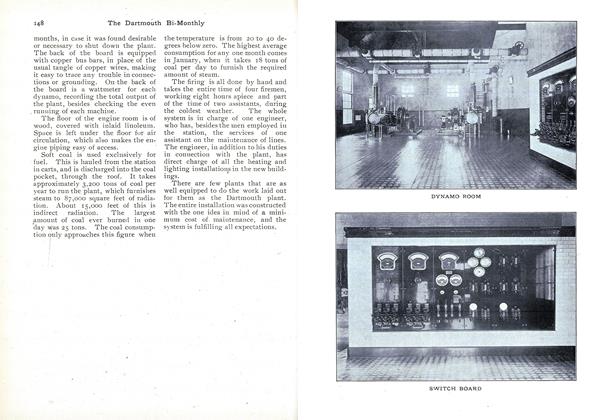

ArticleGETTING STARTED

October 1952 -

Article

ArticleTHE NATURE OF REALITY

MARCH 1989 By Bruce Pipes, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePolitical Experiment Grows

June 1938 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1935 By Herbert F. West '22