A review of the new plan at St. John's College for a curriculum based on great books

THIS ATTEMPT at an assessment of the so-called "New Program" offered by St. John's College at Annapolis, Md., is submitted with much diffidence, because it is obvious that the opinions of a layman concerning educational matters with which he has but an indirect connection must be of doubtful value. Worse still, there is the lively possibility that one not especially versed in such professional affairs will misconceive facts and on such misconception found wholly erroneous conclusions. Hopefully this is less likely when one assuming to express an opinion writes sympathetically, and to a great degree con amore. St. John's College was chartered under that style in 1784, succeeding an older institution, King William's School, which dated from 1696. It is thus among our older colleges, and at the same time is one of the more progressive in the development of ideas in education, many of which have borne abundant fruit. The "New Program" may well prove to be among the most prolific.

It is an avowed attempt to further what is usually and rather too vaguely referred to as a "liberal education." Few expressions have been more abused, and in consequence it is desirable before proceeding further to reach, if possible, an understanding of what "liberal" education means. As understood at St. John's College, it appears to connote that sort of education which best fits a man to adapt himself to his environment—to know the truth which shall make him free. It is the broadening course of study, as against the more narrowing study of the specialist. One might almost say it is the cultivation of background, rather than foreground; or the provision of a firm foundation of general appreciations on which to rear the more detailed intellectual structure in which the useful arts, as distinguished from the liberal arts, will be later emphasized. It is the purpose of the New Program to "recover the great liberal tradition of Europe and America," which for two thousand years has been the guide of Occidental tradition, but which in later years has more and more been lost in the worship of the directly and practically useful.

The central postulate, then, seems to be that education for some time has been tending away from the liberal and toward the utilitarian—a rather natural result, in the United States, where mass education has had such a phenomenal growth—and that it is desirable to bring it back again. For some ten years the faculty and administration of St. John's College have been seeking to discover at what point the thread of the liberal tradition was lost and to set the feet of education back on the liberal path. The New Program is hoped to be the answer.

Now one may safely admit that a great change has come over college education in America since the days when here, as in Europe, the established medium of all liberal education was the study of the Greek and Latin classics, plus mathematics and a smattering of natural sciences. But the field suddenly widened and a hundred fascinating things, apparently more "practical" to know, have crept into the curriculum. The classics—in their accepted and restricted sense—were seen to be ineffective carriers of the liberalizing germ. They were dropped. The difficulty was that in their place nothing was substituted to do the work which "the humanities" had allegedly ceased to do. Instead, a host of supposedly "useful" topics crowded in and the liberalizing became a mere by-product, where it could be said to exist at all.

EDUCATION NOT LIBERAL

This the sponsors of the New Program believe to be failure in a fundamental point, for which there are insufficient compensations in other directions, no matter how good the latter may be in themselves and no matter how interesting or useful they may be to the mass of the students in present-day colleges. In short, education has ceased to stress the liberal; and mankind is the poorer as a result.

From the prospectus of the New Program at St. John's, it would seem that the main idea is to get back to "the classics"— provided one is careful to define that term properly. It would be grossly erroneous to assume that this demand implied a reversion to the old days when sleepy students puzzled out the masterpieces of Greek and Roman literature, lexicon and grammar in hand. By "the classics" one means something much more comprehensive than that —the great books of European thought covering the entire period of history. It is not easy to define a classic with mathematical exactness, but the prospectus sets forth several criteria whereby one may distinguish the weeds from the flowers. A great book in any line is a book that, over a long period, has been read by the largest numbers of persons; it should have proingly inglythe greatest amount of discussion and afforded the greatest variety of intelligent interpretations; it should raise persistent, and often unanswerable, questions concerning the great themes of human thought; it should be manifestly a work of fine art, capable of furthering the discipline of the ordinary mind by its form alone; and it should be a masterpiece of the truly "liberal" arts—the arts of "apprehending, understanding and knowing the truth."

At this point it may be well to give a general idea of the plan at St. John's in detail. It appears to be the provision of two broad avenues, leading in each case to the A. B. degree, between which avenues the student may choose. He may content himself with the curriculum as it has lately been; or he may elect the route laid out by the New Program, on which, once he sets out, he must continue. In it there are no electives—save only the initial election to pursue it. One may not switch into it, or out of it, at any time. Those who follow it must begin at the beginning and stay with it to the end. It is a four-year curriculum, in which every item is required.

The base of the New Program is what amounts to a list of "the best hundred books," carefully chosen and subject to revision, but every book a "classic" in the best sense. The full list of these chosen works is given here; the idea strongly recalls the "Five Foot Shelf" devised some years ago by President Eliot and intended to contain such, a variety of truly great books that a conscientious reader thereof would become a truly educated man, though he never went to any college; only in this present case the student reads under ordered supervision, with seminars, tutorial and laboratory work, lectures and direction, and for satisfactory performance obtains his A.B. Another student, who entered on the same day and elected the other (older) course, would attain the self-same degree by a different route—but one may doubt that he would be equally an educated man.

AN HONEST LIST

Every one, perhaps, has at some time or another made for himself a list of the best hundred books, or a list of the books he would be glad to take with him to some hypothetical desert island. Such lists, especially if made for professorial criticism by college students, are seldom honest. In the St. John's case no such suspicion can exist. This is a literary prescription, carefully compiled to purvey the requisite amount of cultural vitamines. Much of the list the average student would never read of his own choice. These are not the books he would take to a desert isle—or at least most of them are not, despite the inclusion of some of the world's best fiction. But the man who goes through that list in four years' time is bound to be made cognizant of the world's best thought.

The classics are to be read in English translation; but it is apparently the intent to provide intensive study of the original languages of the various authors so that the benefit of what used to be the bone and sinew of "classical" study may not be wholly lost. Devotees of the older days will rejoice in that. Though the real importance of a classical work lies in its thought, rather than in the verbal clothing in which that thought was originally dressed, there is still much to be said for the Greek and Latin as an aid to the intelligent use of English.

Finally, the specific requirements to obtain the A. B. degree include knowledge (demonstrated by semester and comprehensive examinations) of the required books of the course; competence in the liberal arts; a reading knowledge of at least two foreign languages (presumably modern); competence in mathematics through elementary calculus; and goo hours of laboratory science.

A SENSIBLE EXPERIMENT

One may sum it all up as an attempt, not to insure the worldly success of the student, but to cultivate his rational human powers so that he may with a fairer hope meet and withstand the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, as a man among men.

That any such system can be applied with success to mass education is open to debate, but as an effort to recapture the functions of a liberal college it seems an interesting and a laudable experiment along sensible lines. It has long been a favorite theory with the present writer that the great function of education is not to supply its recipient with a cumbrous bunch of keys, each adapted to turn some particular lock, but to provide an efficient master-key which, in the right hands, will open any door whatsoever. To equip the mind to think for itself, even in new and unprecedented circumstances, is the aim. One seeks to build an efficient machine to use—not a well stuffed filing cabinet for predigested lore. Whate'er best serves that end is best.

The proof of every pudding is in the eating, and the full merits of the New Program at St. John's cannot be estimated with accuracy in advance. Neither can its shortcomings be assessed by anything but conjecture. Dartmouth, with its anxiety to preserve, protect and defend the general idea of the "liberal arts" college, is bound to take a livelier interest than most in this fascinating experiment. There may be some criticism of the fact that too little direct stress is laid on the so-called "social sciences." What the St. John's plan does seem well calculated to do is to equip men for what President Hopkins has called "the art of living together" with other men—an art for which, in present conditions, here and elsewhere, there seems to be a pressing need.

ALUMNI TRUSTEE OF THE COLLEGE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

October 1938 -

Article

ArticlePublications Control?

October 1938 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

October 1938 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913*

October 1938 By WARDE WILKINS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

October 1938 By F. WILLIAM ANDES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

October 1938 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Green Derby Contests for 1941

April 1942 -

Article

ArticleInaugural Delegates

April 1949 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1955 -

Article

ArticleThere Is No Music For Our Singing

December 1991 -

Article

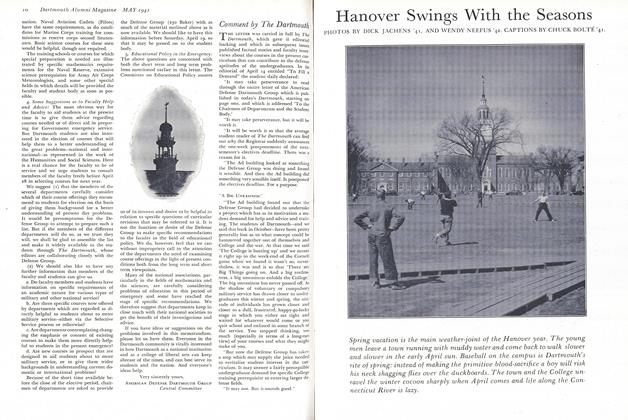

ArticleHanover Swings With the Seasons

May 1941 By CHUCK BOLTE '41 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH BACKGROUND

August 1924 By Eric P. Kelly '06