John Humphrey Noyes, 1830, Pioneer in Communism, Unmarried Love, Contraception, and Eugenics

DARTMOUTH NEEDS heroes, but it won't celebrate those it has. For years some of us have been declaring the greatness of John Humphrey Noyes, but so far Dartmouth is not marked by any memory of one of its most interesting sons. We need at least three hero-symbols here. "The godlike Daniel" will serve as the great man, orator, demigod, and compromiser. Ledyard is perfectly cut to romantic pattern for those who dream of leaving college and going to southern seas and far countries, for he took the third Cook's tour of the Pacific and became one of the first of America's gentlemen adventurers. But we need also a representative of the bold shaper of lives and society, of the man who dares follow his conviction and dream into the future against society and atrophied law. We have him in Noyes, pioneer in communism, unmarried love, contraception, and eugenics.

Noyes was the most subversive and successful radical of a century of cranks, faddists, fanatics, and genuinely great men. While Bostonians were moving out of religion into transcendental idealism and a mildly heretical social experiment at Brook Farm, Noyes burned through churchly accretions and, fired by what he believed primitive Christianity, founded one of the very greatest of all social experiments. This fundamentalist set his feet solidly on ground of which he was arrogantly and even blindly sure, and by the very strenuousness with which he followed Biblical teaching moved to a position antithetic to all the established churches held in reverence. One half of Noyes stands in the twentieth century, the other in the first. We are interested in only one half, which is unfair and misleading. Only out of his absolute and literal obedience to what he believed the principles of Christianity could his purpose come, and only out of the spiritual turning of conversion could his followers come.

In 1830 Noyes graduated from Dartmouth where his father had graduated in 1795 and served as tutor for two years with enough success to be remembered gratefully by Webster. He did not want to be consumed by the religious revivals that were running like emotional wildfire through the country, for he guessed the thorough literalness of his nature and knew that if he found God he would become God's man without reservation or limit. This happened to him. He went to Andover but found only professional bickering, and so he left for Yale. Dartmouth men have gone to New Haven for many reasons. Noyes went in search of God. Studying his Bible day after day he came to believe that the Bible was not a book of riddles, and that if Jesus had said he would return within the lifetime of his hearers he had done so. All unknowingly men had been living under the Christian dispensation, the judgement was over, and men could be free from sin, free from law, even perfect: One needed only to live in Christ and to return to the apostolic church. It was a devastating simplification.

SANITY DOUBTED

Put out of Yale, suspected of being crazy, even by his friends, a prey to the agonies of a soul struggling out of sinfulness into the perfection of holiness, Noyes went home to Putney, Vermont. There he evolved the theory and practice of Perfectionism which were to make him famous and infamous, at once a saint and a fugitive from a warrant of adultery. When he and others founded the colony at Oneida, New York, in 1848, the principles rehearsed in the little group at Putney became the rule of the community.

Out of an unhappy marital experience which brought his wife five pregnancies in six years but only one live birth, came his development of male continence, as he called it. He could not condemn his wife to repeated and unsuccessful pregnancy simply for his own fulfillment. One would not fire a gun at one's best friend merely for the sake of unloading it, as he said. Mai thus and others had been proving the necessity of some control of the birth rate, and he was modern enough to include discovery in this sphere of activity with that in the world of steam power and printing. An- alyzing sexual intercourse he separated the social from the propagative act (a daring step in itself) and stated that union which is within the power of the will, free of fear and social consequence, is a spiritual experience worthy in itself. By training and self knowledge this method of coitus reservatus allows longer, more satisfying, and more significant unions than surrender to uncontrolled and automatic crises.

Although modern knowledge and technique have superseded this early method of contraception, it worked with amazing success. On it were based the institutions of complex marriage and eugenic birth. Men and women were happy and healthy, and birth was regulated in accord with economic wisdom, parental health, and the real desire for offspring which alone can create a proper psychic environment for childhood.

The social reformer had now the means to throw aside the traditional family and introduce a truly communistic society. The giving and taking in marriage, which in Heaven are no more, might be abolished here on earth. With the overthrow of this form of appropriation and ownership true communism of spirit could exist and both crippling celibacy and oppression by individual and legalized lust be done away with. If true love could bind a family into loving union, could it not also bind a whole society with warm regard? Seen largely his principle was not so much the rejection of the family principle as the enlargement of it to include a society of which all members were mutually married. This was not the "free love" which he detested and fought, but an inseparable part of a social regeneration which demanded stability and responsibility.

Unbelievable as it is, over two hundred adult men and women lived under this system of complex marriage in happiness and amity. So far as I can determine there was little jealousy and no nervous disorder. Exclusive unions were not allowed any more than were "sticky" friendships between parent and child or between two boy Companions. Since the very foundation of life was complete and universal love, this growth of spiritual love out of physical desire was accepted as naturally as we accept it in individual unions.

SEX AND COMMUNISM

Every communistic experiment, whether by the Shakers or the Soviet Russians, must recognize the connection of family and property and consider the relation of sex to communism. The most successful communists in America were the Shakers. They held their group together by the celibate denial of love. Noyes used it as the cohesive to bind the community into warm-hearted fellowship. By that he not only provided for perpetuation, but created a more invigorating and satisfying expression of human wholeness, and of relatedness within one social body.

The theory of Evolution by sexual selection shocked an academic world, but Noyes was a realistic farmer who had seen cattle and horses and pigs bred to high standards. So, when Darwin's evolutionary science was destroying the faith of the liberals and intellectuals, the fundamentalist said that "Darwin has been an awful preacher of the law of God." If selection is a law, then "the foundations of a scientific society are to be laid in the scientific propagation of human beings." Long ago Plato had pointed the way in The Republic, but no one had dared to put the theory to action. Noyes always dared. He was not out to discover the ways of God, but to practise them.

He had already destroyed the monogamous marriage which is a bar to scientific eugenics by limiting the active usefulness of the prototype male. He had the perfect man, in this case himself, which as Shaw points out, very greatly simplifies the problem. He had a society in which all children should be equally loved, and in which many adults had already "made themselves eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven's sake." The income and organization of the group were ready for additions to membership. So, in 1869, he inaugurated a stirpicultural experiment in which about one hundred men and women eventually took part—the only great modern experiment in eugenics. Not a mother was lost, there were no defective children, and tables drawn up as late as 1921 show that the children were superior in health and mentality and that they transmitted this superiority to their children.

STUDENT OF SOCIAL THEORY

The firm structure beneath all this adaptation of sex was economic communism of property. This communism had grown imperceptibly out of the close comradeship of people united by the desire to spread the Gospel and to help one another. Its scientific aspects were secondary, though Noyes was a very real student of social theory and wrote one of the earliest books on communism in America.

There is no space here to consider the details and the struggle and the success of communism at Oneida. By 1875 the community possessed 587 acres of gardens, walks, arbors, orchards, nurseries, and vineyards. It had many buildings, a large library, shops, factories, and, characteristically, blooded cattle and horses. Work was by choice, but all work was honored. Difficult and tiresome jobs were softened by every new labor-saving device and by communal simplification. There were games, plays, and creative activity. Women had a high place in the community, and children were brought up intelligently and happily in a non-competitive and pacifist tradition. The much advertised creche and the social consciousness of Soviet youth were established in Oneida fifty years before they were in Russia. Communism worked.

Noyes was a practical business man, and not a mere social dreamer. He looked at the other communities and saw their weakness—land. He kept free of the pseud-Arcadianism of Brook Farm and Fruitlands, and made steel traps and canned fruit in a modern way. "Socialism," he said, "if it is to be really ahead of civilization, ought to keep men near the center of business, and at the front of the general march of improvement." The shrewd Yankee never lost his head in Utopian dreams, and he had in himself and his followers a passion that was an overplus of religious fervor. Without the belief that the Kingdom of God was worth fighting for and that it could be realized on earth, the community would have died in its infancy.

The experiment went into eclipse by the action of the Presbyterian Synod, which could not endure this successful "unchristian" society. Wildly respected, famous as hosts, trusted as merchants, these people were living in social and financial sin. Also there were dissensions from within by the young and the newcomers who had not experienced the original conversion. Noyes, with his usual sagacity, presented a platform that would remove the objectional parts of their living and still leave them Christian communists. Interestingly enough, however, only a year separated their adoption of marriage from their departure from communism and reorganization as a joint stock company. The community has had a successful and honorable career since then, but as a radical social experiment it no longer existed.

I have no desire to claim undue praise for Noyes. I am neither an advocate of complex marriage, a eugenicist, a communist, nor, thank Heaven, a perfect man. Yet I do not see how one can avoid the award of greatness to this practical experimenter in social patterns. Indeed, the wonder is that he is not more widely celebrated. I suspect that his comparative obscurity for a long time came from the fact that he nowhere touches literature. Literature gives immortality to even the worst social fiascos. The Fruitlands disaster and the Brook Farm failure are familiar to us, not for their success, but because Alcott would not use manure in one place and because Hawthorne forked it in another.

PRAISED BY G. B. SHAW

It is time we boasted of Noyes. Havelock Ellis has claimed him "a man too far ahead of his day to be recognized at his worth," but we have no excuse to continue that blindness. Bernard Shaw has called him "one of those chance attempts at the Superman which occur from time to time in spite of the interference of man's blundering institutions." If the possessors of the two handsomest white beards in England will speak of Noyes as a prophet, sure young men should be awake to his worth. Everywhere men are now making reference to him. Look into such varied books as Carl Carmer's Listen for a Lonesome Drum, Gilbert Seldes's Stammering Century, Dr. Robie's Art of Love, or Bernard Shaw's Revolutionist's Handbook, and you will find Oneida and Noyes. In the last two years Robert Allerton Parker has written Yankee Saint, a splendid biography, and Pierpont Noyes was written In My Father'sHouse, the record of his boyhood as one of the stirpicultural children. It is time we dropped our anti-Noyes campaign. Whether or not we agree with Noyes's doctrine, let us not be the last to respect him as a bold and courageous leader, nor the last to claim him an honored son of Dartmouth.

FAMOUS ARTIST JOINS DARTMOUTH FACULTY Paul Sample '21, who assumed the post of Artist in Residence this fall, shown givinginformal art instruction in his Carpenter Hall studio.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1938 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1938 By "Whitey" Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

November 1938 By The Editor -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1938 By EUGENE D. TOWLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

November 1938 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

November 1938 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY

ALLAN MACDONALD

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

May 1934 -

Books

BooksCLIPPER SHIP MEN

December 1944 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksWAR AND THE POET

January 1946 By Allan Macdonald -

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AT SEA

January 1946 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleCharles Edward Hovey '52

April 1947 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Books

BooksHERMAN MELVILLE

December 1949 By Allan Macdonald

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE GETS LARGE BEQUEST BY WILL OF LATE S. H. STEELE

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

June 1947 -

Article

ArticleClub Events for Summer

July 1949 -

Article

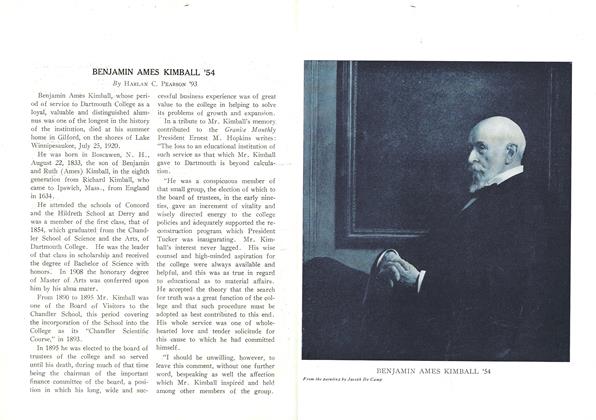

ArticleBENJAMIN AMES KIMBALL '54

November 1920 By HARLAN C. PEARSON '93 -

Article

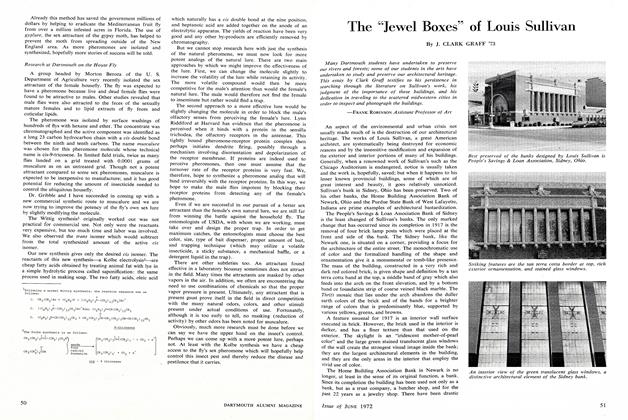

ArticleThe "Jewel Boxes' of Louis Sullivan

JUNE 1972 By J. CLARK GRAFF '73 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

NOVEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin