Curriculum and Extra-Curricular Activities Discussed from Student Point of View

THERE WAS NO joy in Mudville..... That's the way Hanover felt, too, after the game at Ithaca. Up to now it had presumed twenty-two victories had pointed merely to twenty-three; but there had to be a reckoning sometime. So Hanover shrugged its shoulders, took a hitch in its pants, let down the awning, put on the lights and went about its business.

For there were some other things on its mind (even though in retrospect it would like to have hung Cornell's scalp up to dry like the rest). There were, besides sports, curricular, extra-curricular, recreational, social, political, and even religious activities—all these interests have a pigeon hole in the Dartmouth man's mental desk.

All of these have their implications, present to him their problems.

THE CURRICULUM

There's reason to believe that students enjoy taking advantage of the freedom of the elective system, which not so long ago was unknown. The College's plan of a general training in as many of the cultural fields as possible, climaxed by the last two years' integrated specialization in one field, is agreeable enough to students. So is the relatively recent appearance of the social sciences, which deal more primarily with ideas and trends and illustration than with high-schools and early-college factcramming gymnastics. Welcome also are a welter of stimulating electives quite often along vocational lines and more often than not (because of the personal choice factor) quite intensely energizing to the student's imaginative and productive elements.

Yet there still exist plenty of incidents like the following which occurs in one major department. The course is required so every student majoring in the department quietly pays his $45 and goes to class. After four weeks have passed the entire group without a dissenting member will agree to this: that truthfully and sincerely they could epitomize in two lectures what the professor has prattled on about in four weeks; that they sit uninspired in a mental vacuum in class merely to be marked present; that the material required in readings and quizes is as unimportant as far as their more lasting knowledge of the subject is concerned, as last year's Sears-Roebuck Catalogue; and that in view of other grievances there should be a concerted appeal to the head of the department—that something should be done about it.

That appeal was made and the answer was this: "I'm afraid that will have to stand; you've got to have at least one hard course."

That this sort of thing is the exception rather than the rule, is gratifying. Yet the existence of this sort of course and this attitude points probably to one conclusion; that it is a hangover from the days when most all education was a bitter pill to be swallowed in lip-service to Mental Discipline. If mental discipline is attributed to crammed information, irrelevant and insignificant stuff learned and forgotten an hour after the quiz, the process fails. If this sort of subject-material pretends to stimulate, it fails. If it pretends to teach men to think, it fails. If it derives glassy-eyed satisfaction that it has accomplished something educational by goading the boys into grindstone work that raises, instead of interest and inquiry, an arrogant antipathy—it has failed again.

The old idea that it isn't what you learn that counts, but rather the amount of time you spend on it, and how hard you have to work, breaks down somewhat in this day when individual, personalized education is so important—and the interest and participation of the individual is regarded so highly. Today the assumption is that Dartmouth as a liberal college is interested in developing students' minds by giving them career-relevant material, which, by interesting them makes them think, makes them contribute. That this is not accomplished by the bitter pill course and attitude mentioned above, goes without saying.

It isn't sheer madness to assume that students expect to, and will take up their end of the load, work willingly in subjects which have even a semblance of interest. They're human beings who, it is true, actually challenge the professor and his material to interest them, and it is his duty to succeed, as so many of his cohorts have, in making that material live and palatable and if possible, vital to present day affairs. Students have found the twentieth century liberal arts modification (with its electives, major work, personal elements: field work, contribution) an interesting challenge in contrast to the impersonal, coercive program of 1840—and it is only natural that they should expect the rest of their program to follow suit.

And yet some elements of nineteenth century education, as exemplified by the case above, hangs on into the twentieth.

How long before the cultural lag will be destroyed?

EXTRA-CURRICULAR ACTIVITY

Extra-curricular activity takes a rather depressed stand at Dartmouth.

With the entrance of a new class, the College is careful to make its standpoint clear: your academic work is all important, and the concentration should rest there. Later however, if you have time, extracurricular activity is a good thing. On the basis of this philosophy (and it is justifiable that academics should come first) the tendency has been to make the Freshman year impressively hard enough so that the academics-preferred relationship is maintained.

Yet extra-curricular activities are suffering for it. All through the twenties and even into the early thirties, organizations such as The Outing Club, The Players,The Dartmouth, reported excellent turnout in their competitions. In the last few years, however, these organizations have shown a marked decrease in participation. It may possibly be caused by an increase in the number of organizations; but it is much more likely that the Freshman are strenuously impressed with the importance of getting going academically in their Freshman year, so they give up temporarily the thought of extra-curricular activity.

It would be fine if they devoted their extra time as was intended—toward special concentration on studies—but what hap- pens is, their spare time is neither spent on academic work nor extra-curricular activities. It is wasted. Thus at a time when a Freshman should start "opening up," looking horizonward, developing interests, and becoming somewhat efficient as far as planning his time is concerned—he is virtually drying up like a pea in a shell. And in many cases his academic work is worse than as if he'd had some extra-curricular activity which would have made him plan his time.

There are, it is true, a considerable number of students in extra-curricular activities, but the directors of The Players,The Outing Club, and The Dartmouth will concernedly point out to you that undergraduate participation and interest is far, far from what it should be, and what it has been; and ability and talent remaining undeveloped, go to waste.

Almost all extra-curricular activity at Dartmouth is extremely worthwhile—both from the standpoint of personal development and contribution, and that of liberal academics: learning journalism in all its phases in the model Dartmouth plant editorially, technically, and from a business standpoint; participating in dramatics with The Players, on the stage and in the wings; participating in the musical clubs; public speaking in the Speakers' Bureau, debating in the Forensic Unionall these activities are the more practical approach in a liberal training, to outside life.

And yet at a time when all liberal education points more and more to the position where self-realization and the student-contributory factor is increasingly important—extra-curricular activity remains entirely divorced from academics at Dartmouth. No academic credit whatsoever is given any of the above activities. There is even no prospect that academic credit will be given in connection with the new Webster theatre project.

There is no formal Administrative policy concerning extra-curricular activities. Faculty sentiment seems divided among those who discourage extra-curricular activity, and those who don't encourage it, the former group probably outweighing the latter. They, of course, are interested —and justifiably so—in the proper emphasis on studies. May it be emphasized again, however, that any such plea for a definite policy toward strengthening extra-curricular activity at Dartmouth does not presuppose that it should "replace" academics.

It is a plea to divert the bad habits of wasted undergraduate time and energy into useful channels, and to give extracurricular activity, now quite out of joint with the academics of this College, the place it deserves in a liberal Dartmouth atmosphere.

(Next month we would like to continue with the Dartmouth man's social life: dormitories, fraternities; his philosophy of life: political, economic, and religious outlook).

SCENE FROM THE PLAYERS' HOUSE PARTY SHOW, "BROTHER RAT'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFootball Review

December 1938 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

December 1938 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1938 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

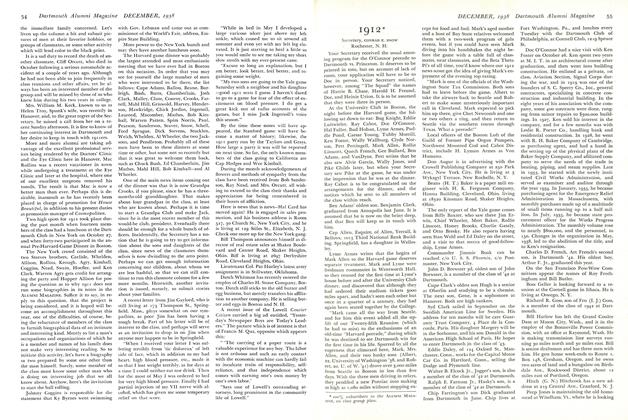

ArticleProposed Mew Webster Hall

December 1938 -

Article

ArticlePublications Decision by Trustees

December 1938 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1938 By CONRAD E. SNOW