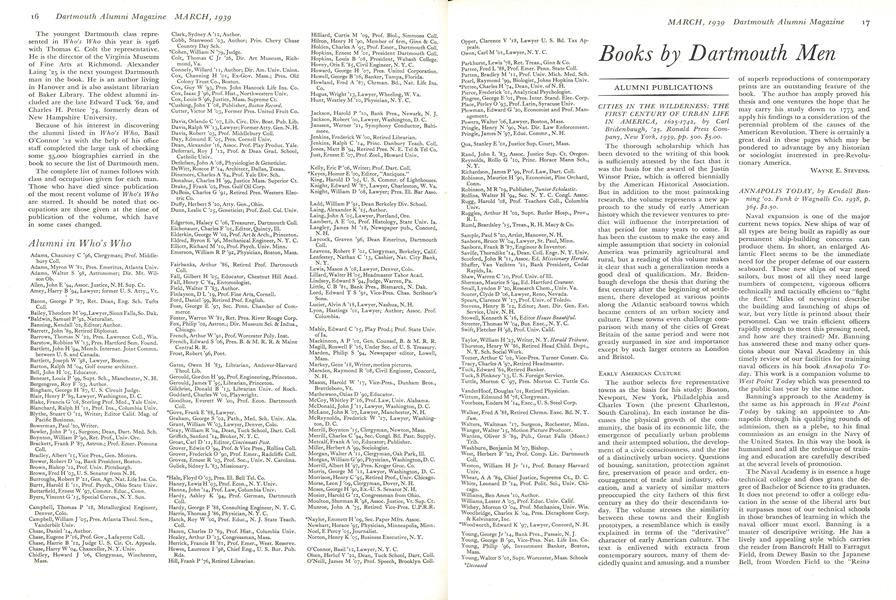

CITIES IN THE WILDERNESS: THE FIRST CENTURY OF URBAN LIFE IN AMERICA

March 1939 Wayne E. Stevens.1625-1742, by CarlBridenbaugh, '25. Ronald Press Company, New York, 1959, pp. 500. $5.00.

The thorough scholarship which has been devoted to the writing of this book is sufficiently attested by the fact that it was the basis for the award of the Justin Winsor Prize, which is offered biennially by the American Historical Association. But in addition to the most painstaking research, the volume represents a new approach to the study of early American history which the reviewer ventures to predict will influence the interpretation of that period for many years to come. It has been the custom to make the easy and simple assumption that society in colonial America was primarily agricultural and rural, but a reading of this volume makes it clear that such a generalization needs a good deal of qualification. Mr. Bridenbaugh develops the thesis that during the first century after the beginning of settlement, there developed at various points along the Atlantic seaboard towns which became centers of an urban society and culture. These towns even challenge comparison with many of the cities of Great Britain of the same period and were not greatly surpassed in size and importance except by such larger centers as London and Bristol.

EARLY AMERICAN CULTURE

The author selects five representative towns as the basis for his study: Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia and Charles Town (the present Charleston, South Carolina). In each instance he discusses the physical growth of the community, the basis of its economic life, the emergence of peculiarly urban problems and their attempted solution, the development of a civic consciousness, and the rise of a distinctively urban society. Questions of housing, sanitation, protection against fire, preservation of peace and order, encouragement of trade and industry, education, and a variety of similar matters preoccupied the city fathers of this first century as they do their descendants today. The volume stresses the similarity between these towns and their English prototypes, a resemblance which is easily explained in terms of the "derivative" character of early American culture. The text is enlivened with extracts from contemporary sources, many of them decidedly quaint and amusing, and a number of superb reproductions of contemporary prints are an outstanding feature of the book. The author has amply proved his thesis and one ventures the hope that he may carry his study down to 1775 and apply his findings to a consideration of the perennial problem of the causes of the American Revolution. There is certainly a great deal in these pages which may be pondered to advantage by any historian or sociologist interested in pre-Revolutionary America.

ALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

Wayne E. Stevens.

Books

-

Books

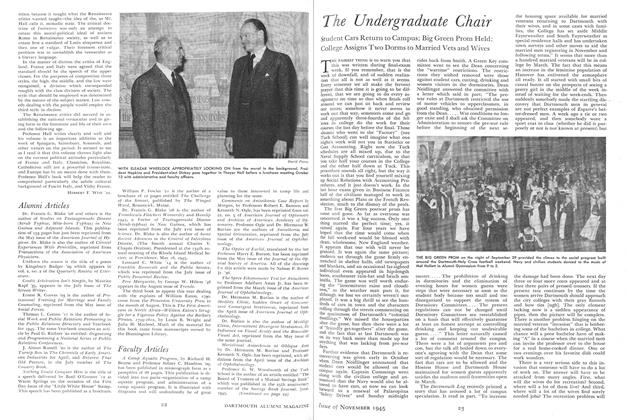

BooksUNDERGRADUATE

NOVEMBER 1931 -

Books

BooksPhiloprogenitive Bird

December 1975 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksIT'S A WISE PARENT,

November 1945 By M. D. F. -

Books

Books* DARTMO UTH OUTING CLUB HANDBOOK.

February 1933 By N. L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksGRAY MATTERS, A NOVEL.

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksJOHN LEDYARD'S JOURNAL OF CAPTAIN COOK'S LAST VOYAGE.

JUNE 1964 By W. RANDALL WATERMAN