By Maurice Mandelbaum'29. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press,1964. 262 pp. $6.50.

This book consists of four essays: Locke'sRealism; Newton and Boyle and The Problem of "Transdiction"; "Of Skepticism WithRegard to the Senses"; and Toward A Critical Realism.

In the first essay the author argues persuasively that the "orthodox" interpretation of Locke's account of the relation of ideas of primary qualities (ideas of bulk, figure, number, and motion) to those qualities themselves is mistaken. It is contended that given Locke's acceptance of atomism, he could not have held that, "our ideas of the primary qualities of macroscopic objects exactly resemble those qualities as they exist in the objects themselves" (p. 18). The primary qualities of bodies are those which cause our ideas, not those which resemble our ideas. A "transdictive" inference is one which proceeds on the basis of observed data to a conclusion about objects or events which are in principle unobservable.

In essay two Mandelbaum discusses the use made of and the justification provided for such inferences by Newton and Boyle. The Importance in the history of thought of this mode of inference is indicated by the author's remark that, "What had become clear to those who investigated natural phenomena was that transdictive inferences were necessary to account for the facts of ordinary experience" (p. 235). The third essay is intended to show that Hume's critique of realism fails in that it presupposes the truth of the very doctrine being attacked. In the preface Mandelbaum says of these essays "While each is independent of the others, and the argument of each is to be judged on its own merits, there is at least one theme common to them: the question of how one might hope to establish or to defend a critical realism." The fourth essay is devoted to this end. "Realism" as an epis-temological position is the view that good reasons can be given for believing that there exists independently of sense perception, a world of physical objects, and that it is possible to come to know at least some of the properties of those objects through sense perception.

The particular variety of critical realism that Mandelbaum advances he calls "radical critical realism" which embraces the realist thesis as stated above and adds the contention that "we do not have the right to identify any of the qualities of objects as they are directly experienced by us with the properties of objects as they exist in the physical world independently of us" (p. 221). This is not to say, however, that directly experienced qualities may not accurately mirror the properties of physical objects. A familiar objection to this bifurcation of sensed qualities and physical properties is that it generates an impassable evidential gulf between what we are directly aware of in sense experience and the properties that we judge the objects of our sense experience to possess. The contention is that an inescapable consequence of critical realism is that its defenders paint themselves into a corner of subjectivity and, finally, solipsism.

Mandelbaum's attempt to counter this criticism draws heavily on his claim that an adequate philosophical theory of sense perception must take into account the relevance of the findings of the sciences of physics, physiology, and psychology. This claim is quite at variance with a currently fashionable view in philosophical circles, viz., that one must know about science only so much as is required to make evident the irrelevance of scientific results to philosophic inquiry.

After a very thorough and well documented argument Mandelbaum concludes (p. 245) that it would be "unwarranted" to say that what we perceive is identical with physical objects existing independently of perception. Thus physical objects are inprinciple unperceivable, and yet we can know about their properties and relation. The justification of such knowledge claims would consist in a detailed description of the scientific inquiries on the basis of which the claims have been advanced. To the question of the adequacy of such justification Mandelbaum's reply is that the general methods employed throughout the development of modern science constitute a model or a paradigm of what justified reasoning consists in. And it is no good asking whether a paradigm case of right reasoning is really right reasoning. A review of this scope cannot possibly do justice to the richness of this book. It is well worthy of the attention of scientists and historians of science as well as philosophers.

Associate Professor of Philosophy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

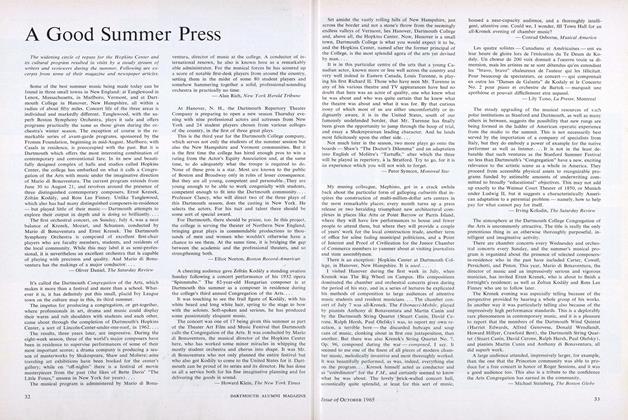

FeatureThe Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College

October 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureA Good Summer Press

October 1965 -

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

October 1965 -

Feature

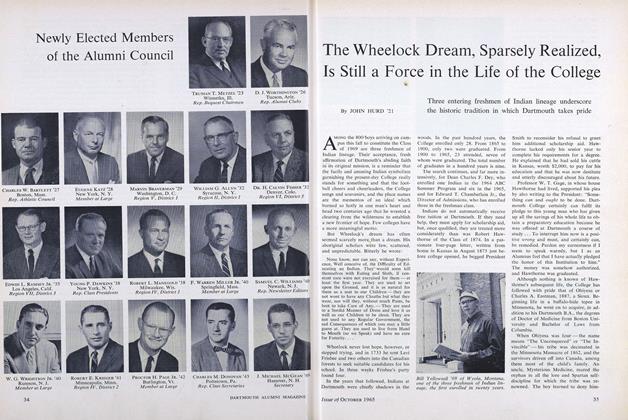

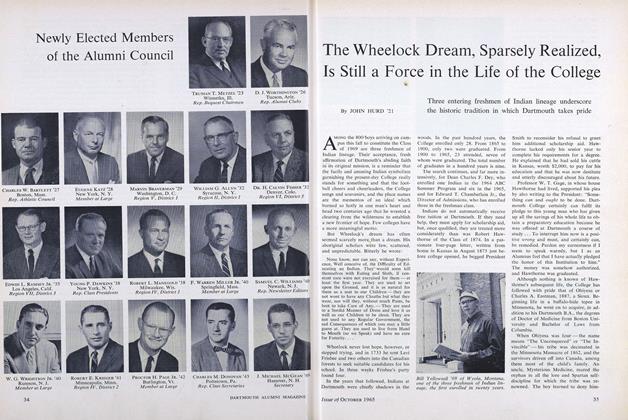

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

October 1965 -

Article

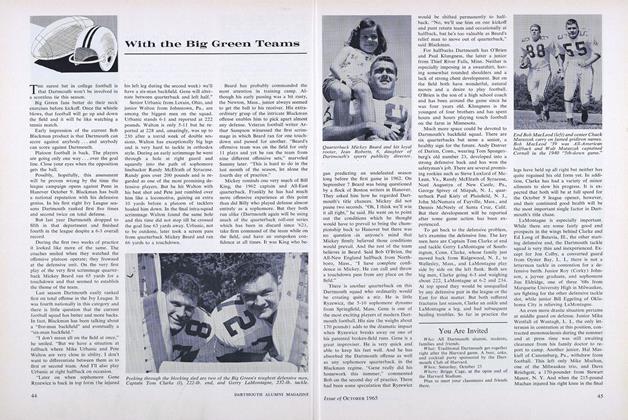

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

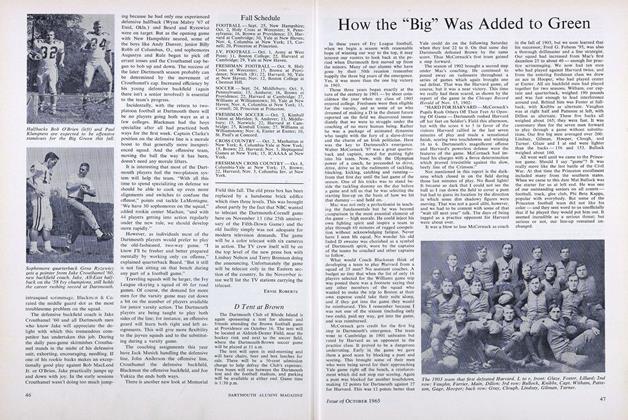

ArticleHow the "Big" Was Added to Green

October 1965 By W. HUSTON LILLARD '05

TIMOTHY J. DUGGAN

Books

-

Books

BooksYOUR HEARING, HOW TO PRESERVE AND AID IT.

April 1933 -

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

March 1947 -

Books

BooksIDEAS, WEALS, AND AMERICAN DIPLOMACY: A HISTORY OF THEIR GROWTH AND INTERACTION.

OCTOBER 1966 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksHIGH TREASON

October 1950 By Robert B. Dishman -

Books

BooksEARNING OUR HERITAGE:

June 1938 By Stearns Morse. -

Books

BooksTHIS IVORY PALE.

NOVEMBER 1970 By WALTER W. WRIGHT