One of the Foremost Teachers Is a Versatile Man Of Varied Interests and Distinctive Achievements

MEN WHO HAVE NOT had much experience with college professors sometimes may quote with what they hope is profundity that he who can, does; and that he who can't, teaches. If a college faculty had to choose a single man whose mind and activities could give the lie to any such assertion, they would not have to look any farther than the office in Wilder Hall of Professor Charles A. Proctor.

Business executives have continually sounded out President Hopkins about the chances of getting Mr. Proctor. Indeed when the President had in days gone by a position with the Western Electric Company, one of his first jobs was to try to engage Mr. Proctor, and the Company was not content with one refusal; it sent him back three or four times. Mr. Proctor's answer was, "Hop, why are you wasting your time?" He had always wanted to teach at Dartmouth, and that was all there was to it.

Mr. Proctor's friend of 45 years standing, Clarence G. McDavitt 'OO, himself a business man, is sure that if Mr. Proctor had wished to accept one of the business offers he has received continually, he would have been one of the outstandingly successful men in his field in America with a salary in keeping. Merely to entice him away as a beginning, organizations were willing to offer him four times what he is receiving at Dartmouth.

As a research man in physics and mathematics, Professor Proctor is so gifted that E. Gordon Bill, Dean of the Faculty, is convinced that if he had lived in a university environment, he would have become a great research scientist. His colleague, Professor Hull, believes that if Professor Proctor had devoted himself exclusively to the laboratory, he would have become a producing scholar of distinction.

And what is true of his vocation is also true of his avocations. He has always done everything in which he was interested superlatively well. In spite of his slender build he was a great football player in college. He was one of the leading tennis players in this part of the world. Years ago he was an exceptional cabinet maker, and he helped to build his own house and the billiard table in it. He has always been a marvelous nature photographer. He is one of the best billiard players on the faculty, one of the best bowlers, and one of the best golfers. He knows more about skiing that almost anyone in the United States. No one can estimate the number of hours he has put in on committees working for the good of the College.

Mr. Proctor is the Robert Frost of scientists in the sense that he is the kind of man who ought to live in a college community even if he did not teach a single class. His mere presence about the campus lifts the morale of faculty and students and townspeople. Ask anyone about him and you will get the answer that he has never had a mean thought about a person and yet is no Pollyanna. So level headed is he that he has never had to take back a statement which he has once made, and yet he is by no means taciturn. Look at him, say any number of his friends, and you will be convinced by his appearance that he is a man essentially sound and accordingly happy. And though he knows many persons, he is intimate with only a few. So genuine and real is he that he has a natural ability to uncover sham and a false front, and though he can be sarcastic on occasion, he has a tendency nevertheless to look for and find the best among his associates and to act positively in terms of excellence. He has so highly developed a sense of justice that after he has surveyed the facts in a situation and made a pronouncement, you might just as well accept it as being as near to the truth as it is possible for a man to get.

Though Professor Proctor could adjust himself to any campus, any Hanoverian would have difficulty in thinking of him as living outside this college. He is Dartmouth through and through, not only because of his innumerable and varied services to the College but also because of family ties which go back to the days of his great-grandfather, Ebenezer Adams of the class of 1791, Professor of the Learned Languages from 1810 to 1833, and acting President on various occasions.

His father. John C. Proctor, professor of Greek at Dartmouth, who died in 1879 at the age of only 39, had already made a strong impression on the undergraduates both by his scholarship and attractive personality.

His uncle, Charles A. Young, was professor of astronomy at Dartmouth, but the poverty of her equipment and financial resources at the time enabled Princeton to entice him away in spite of Dartmouth's efforts to retain him. His investigations with the spectroscope, then newly applied to astronomical work, his discovery of the reversing layer in the solar spectrum and other important observations won for him international repute as an authority on the sun. During his term at Dartmouth, on four occasions he was absent for astronomical investigations; he went to lowa and to Spain to study eclipses, to China to observe the transit of Venus, and to Wyoming for other investigations. His renown as a scientist and astronomer was no more widespread than his popularity as a teacher at Dartmouth and at Princeton. Appropriately enough, he was nicknamed Twinkle.

Mrs. Proctor, Charles's mother, after the untimely death of her husband occasionally took in college roomers, and President Hopkins lived in her house for a while. Small, nervous, and competent, she proved herself as brave a little woman as she was spritely, always pretty, moving about in a staccato fashion like a chipping sparrow or a robin.

John Proctor, Charles's brother, after teaching in a boys' school for a while and studying medicine, taught mathematics at Dartmouth, and he proved himself, so older inhabitants say, a superb instructor. He went to Milton, New Hampshire, where he practised medicine for many years.

Brought up in Hanover, Sarah Proctor, Charles's sister, married Professor Sidney B. Fay, formerly of Smith College and now teaching at Harvard.

Even before her marriage the present Mrs. Proctor had connections with Dartmouth, for she was the daughter of Dr. Charles Nancrede, Professor of Surgery at Ann Arbor, who used to lecture at the summer sessions of the Dartmouth Medical School, and that is where the romance between her and Charles Proctor began. Mrs. Proctor's reputation as one of the most charming women in Hanover has long been established, and her friends praise her white hair, which turned in her twen. ties and added to her air of distinction, her very blue eyes, her beautiful figure, and the aristocratic backgrounds of her with its noblesse oblige, its simplicity, and unaffected graciousness.

Yankees are proud of being Yankees, and Hanoverians think of themselves as special Yankees and are almost as proud in their quiet way of being Hanoverians as Bostonians in their noisier way are of be. ing Bostonians. It seems right that Charles Albert Proctor, an offspring of one of the oldest and soundest families in Dartmouth history, should have been born and brought up near the campus—on the site of the old Tuck School, now McNutt—in a little New England square homestead, built in 1810, by Professor Ebenezer Adams, his greatgrandfather. Not until Charles was 13 did he sleep away from home—he spent a night on Moosilauke—but he finds such lack of mobility not untypical. Undergraduates in his day never shoved off with a horse and buggy to take dinner in Northampton just for the sake of letting the wind blow through their hair.

The premature death of Charles Proctor's father forced his mother to bring up the three children on about S 1,000 a year. This seems like little money even in a college community, but Charles as a boy did not feel the pinch of pennies and new believed that he was a poor lad. At any rate he never felt called upon to do odd jobs to pick up a bit of spare silver before the age of 13, and even then he might not have known the rewards of honest toil in terms of dollars and cents if one of the

Wards had not been hired to move the old museum from Culver to Butterfield, that hideous yellow structure where is now the grass plot in front of Baker Library. He worked all summer and did not make much money, for wages were low in those days. On a steady job Charles got a dime an hour pumping the organ for his brother, but he pumped so well and kept his mind so concentratedly on his work that he was eventually raised to fifteen cents an hour.

The young Charles Proctor got his first schooling here in Hanover, and then, a' high school age, he went to Worcester Academy, where he trekked around with Theodore - Chase, who ran a life insur. ance business in town until his death last year. Tedo could show him the ropes, for he was two years older, and, of course, a lot wiser.

Charles Proctor did not spend his o hours doing those entertaining problems about a man rowing a skiff up a stream at three miles an hour when the current flowing down four miles an hour and the wind is blowing 15 miles north north east how long would it take a man to row diag onally across if the stream were flowing by south and the man had a 30 per cent astis?natism, were a poor rower, and the visibility hazy- No doubt he could have done this problem and allowed for the right number of crabs, but he recalls simply that he liked math and sciences in those days better than languages and history.

It was in Worcester that Charles Proctor probably saved Ernest M. Hopkins for the College. The President had to leave Dartmouth during his freshman year because he lacked money, and it was a bad time for him, a sour time, as he himself puts it, when he saw life in blues and blacks. He did not know whether he should ever have the courage to return. A letter came from Charles Proctor that he would be at a Worcester track meet and he proposed the two should meet. Mr. Hopkins was too depressed even to attempt to send a reply. Coming home from work in Uxbridge, Mass., in the late afternoon of the track meet, he found that his friend Charles had hurried away from the track meet and had covered the intervening 18 miles by train to give him the arguments for returning to College and to offer him the opportunity of saving the cost of room rent by rooming with him. The combination of affectionate regard in which Mr. Hopkins held his friend, the persuasiveness of Mr. Proctor's fight talk, and the kindly proposal which relieved him of the necessity for the year of paying room rent produced the will and the possibility for him to return.

Charles Proctor entered Dartmouth when he was still 17. Boys in those days often entered much younger; Mr. Proctor's brother, the doctor, graduated at 19.

In Worcester the name of Proctor had meant something to the football team, the baseball team, and the track team, and so it was not entirely unnatural that a man who knew his way about among the leathers, horsehides, and spikes should turn to D.K.E. at Dartmouth. There he formed close friendships with Clarence McDavitt and the late Natt Emerson, both class of 1900.

PROFICIENT WITH SPHERES

Even in those days fraternities urged their members to show their stout hearts when competing for prizes in games concerned with spheres of various sizes,'and arles needed no urging. President Hopins says that Mr. Proctor could have been an excellent baseball player, for his motor exes are extraordinary, but he preerred to devote himself to track. Mr. Procor says that he wanted to become a hurnaturally enough, for Steve Chase had broken the world's record, and acoordingly all the Hanover talent tried to Masquerade as genius. He tried and tried, but, as he himself says with a humor which he probably did not possess in those days was terrible." Somehow he got the idea that a body hurtling through space could make time if the line of trajectory were thinned down, and so he took off about five feet before he reached a hurdle and landed about ten feet beyond. He studied these angles, became acutely conscious of his defects, increased his wind and leg power, and finally won his D in the Brown meet senior year.

The name of Charles Proctor appeared on the football field. He weighed 165 pounds, which was absurdly light in those days of mass plays. All his friends brought up in the tradition of ice-men and coalheaver builds refer to Mr. Proctor's as ridiculous, but the professor himself says today without shyness and without conceit, "I was fairly strong." Just how much granite there should be in the muscles for a Dartmouth man in the iBgoties, the Professor of Physics is no doubt too scientific to specify; he prefers to go on to another simple statement, which comes out as an afterthought as if by way of consolation for his lightness, "I was a good punter." If you look back into the files of The Dartmouth of 1899, however, you will find that the sports writers who covered games in less glowing language that the word-strainers of the present day give Mr. Proctor more praise than he gives himself.

SUPERLATIVE PUNTING

Reporting the Dartmouth-Exeter game, which we lost 16 to 5, The Dartmouth printed (Oct. 6, 1899), "At fullback, Proctor punted well and when called upon never failed to carry the ball through the line for a gain."

Commenting on the Yale game, which we lost 12 to o before 3,000 spectators, described as "a howling mass," the sports writer records, "Jennings, Proctor, and Farmer went through old Eli's line as if it had been paper." And farther on, "Proctor did excellent work, bucking with a force almost inconceivable for a man of his weight."

This was the season when the College was stirred by the pros and cons of shouted advice and comments from the sidelines. The Dartmouth took a conservative stand and considered such behavior not only illegal but also indecorous, and it ran a redhot editorial on October 13, 1899, which makes queer reading in November, 1940.

"Clean and brilliant as was the game last Saturday, in so far as the work of the team was concerned, the whole performance was sullied by the disgraceful conduct of a few men along the side lines and their imitators in the grandstand. Coaching from the sidelines is contrary to the ru'es of football: coaching accompanied by derisive and vulgar vituperation directed against the opposing team, is contrary to the rules of decency as well. .... Cheering for one's team is a splendid thing. There is inspiration in the power of lusty voices sounding the old college yell. The desperate appeal of the reiterated "Dartmouth, Dartmouth, Dartmouth," has more than once steeled weakening muscles, roused flagging courage, turned a retreating team into a moveless wall and snatched victory from defeat. But there is nothing courageous in hitting a man when he is down; there is nothing funny or helpful in bawling out witticisms at the expense of a losing opponent. Such action is, to say the least, unsportsmanlike; outsiders would characterize it by a stronger term. Howls of "kill 'em," "rip 'em up" savor of the prize fight rather than of a college contest, which is supposed to bring together the flower of America's young manhood. If we cannot win, save by such methods, we would better abandon athletics, and cultivate the innocuous and refining pursuits of knitting and embroidery until out gentlemanly instincts have had further time for development."

FORTY-ONE YEARS AGO

The year 1899 was a disastrous one in Dartmouth football, and the fault evidently was not in the fans who cheered, as is indicated, a trifle too raucously for the editorial writer's taste.

High hopes rose in undergraduate hearts before the Columbia game, the high point of the season, but the team made a poor showing. "With the exception of Captain Wentworth and Proctor at fullback," said The Dartmouth sternly, "hardly a man played with the nerve and the spirit which has usually by characteristic of Dartmouth elevens."

This may have been the game which Mr. Proctor had in mind when he referred to himself as a good punter. "Proctor's punting was far better," one finds written in The Dartmouth, "than that of Morley" (Columbia's right halfback); "indeed, some New York papers state that such punting has never been equalled on Manhattan Field. One thing, however, is certain; it was Proctor's heady work that kept Columbia from winning by a much larger score."

Looking back 41 years to that contest, Mr. Proctor feels still that there was something funny about the ball. It must have been light, he believes, for a queer thing happened to him time and time again in that game, and it had never happened before and never afterwards. He found that he kept kicking himself clean over backwards and falling on his neck.

If Mr. Proctor played good football, he played better tennis. His D.K.E. running mates did not know that they had a potential champion, for in those days Dartmouth had no tennis courts to speak of, and so he did not have a chance to prove what he could really do until he did graduate work in Chicago. There even he himself admits that he was number one for several years, but as if to take away quickly any suggestion of boastfulness, he adds that there were three or four chaps who could beat him.

As late as this past summer, before Mr. Proctor caught a cold that developed into a slight pneumonia he played some tennis. It was the first time he had had a racquet in his hand for 22 years. His glasses with their bifocals did not help. "The first time I took a swat at the ball, I missed it by a foot," he says with his usual good-humored objectivity, "but I was anxious to see what I could do.

The reason why Charles Proctor found himself in Chicago was that he won the Parker Fellowship from Dartmouth, and a senior fellowship which he gained there helped to persuade him to stay on. During his last two years and a quarter in Chivro he served as research assistant to the treat Polish-born physicist, Albert Abraham Michelson, who died at the age of 79 in 1931- Di - Michelson was the first American scientist to win the Nobel Prize, and his greatest achievement was the construction of the interferometer that bears his name, and its applications to the determination of the standard metre in Paris, to the measurement of the angular diameter of a star (Betelgeuse) for the first time (1920), and to an attempt, made in collaboration with Morley, to detect the motion of the earth through the ether. The negative result of this experiment was the prelude to Einstein's Theory of Relativity.

From Chicago Mr. Proctor moved on to the University of Missouri where he stayed for four years as instructor in Physics, and then at long last came his call from Dartmouth to teach in the department of mathematics in which he had taken a minor in Chicago. Following a year's teaching he went back to Chicago to finish his doctorate with a thesis on so esoteric a subject that he does not like to mention it to a layman, perhaps because he might sound overscholarly. There he experienced the bitter disappointment which comes so often to research scholars: another scientist, R. W. Wood at John Hopkins, working independently had done the work ahead of him and beat him to publication. And so to change the capital M. to a capital D.(Mr. to Dr.), Charles Proctor had to work up another subject, the variation of the mass of electrons at different velocities, and on this topic he got busy and labwed so assiduously that he got his thesis done before anyone else could.

On returning to Hanover as an assistant professor, Mr. Proctor with his wife moved about from faculty house to faculty house, snapping up places vacated by members of the faculty going on leave. Such gypsying about is easier on the husband than on the wife, or at least so it is said, and the Proctors consequently built their present house in 1910. On a construction job a physicist can put in a lot of effort if he has the gumption to, and Professor Proctor has never been a man afraid to get his hands dirty or calloused. Not content with the white-collar work of drawing all the plans, he took the overall job of pouring the concrete himself and doing all the wiring. He hired a boss carpenter, who did what the Professor told him, and the Professor did what the boss carpenter told him, and there was a cheerful old-fashioned division of labor in which things got done and done right and not much more slowly than nowadays. The world has changed, as Mr. Proctor points out, and no longer it is possible, he thinks, for an energetic person to do what he did: he would have the union on his neck.

PIONEER SKIING

All that building was fun, and fun it was to go skiing. Fred Lord and Charles Proctor used to go out on skis a half inch thick, with only a toe strap that held the foot in very loosely, and one and only one long pole that they leaned on at a slant. They never thought of taking turns. Gravitation and a hillside were all that they had their minds on. They kicked off their skis at the bottom of the slope, if indeed the skis had not already come off on the way down.

Much more popular than skiing in the old days was snowshoeing; in fact, not many Hanover persons had skis; not until the days of Fred Harris did men use anything approaching modern bindings. Before his time, for every ski race at Carnival, there would be six snowshoe races.

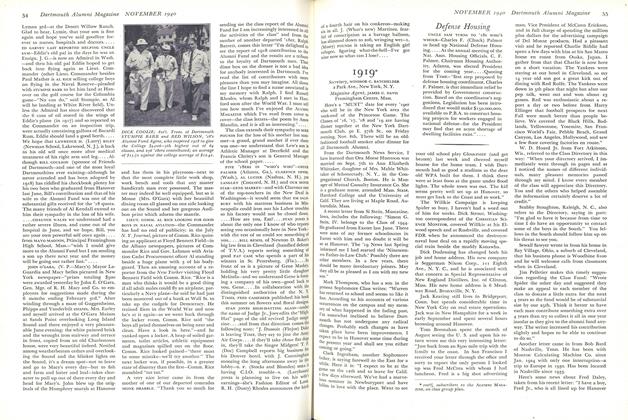

Charles Proctor's elder son, also named Charles, a Dartmouth graduate in 'sB, used barrel staves when he was only five, and his father used to go out on the hills around their house with him for the fun of it. But little Charles as he grew bigger used to ski all day long, and so big Charles went to Storrs' Bookstore and bought the only manual there was on the subject, Caulfield's How to Ski, went home, read it, and understood it, but he says that he was never any good because he was too lazy to work at it. The "it" means downhill running, of course, and would be the natural idiom for the father of a champion skier to use.

If Charles the Elder was a bit lazy on skis, Charles the Younger was not. He skied himself right into the Olympic class. In point of fact, however, it was not quite so easy as that. Young Charles used to be scared to death of jumping, and he had other psychological handicaps, unbelievable though it may seem now to anyone acquainted with his spectacular successes in competition with the best skiers here and abroad ten years and more ago.

To help his son through these difficult times, Mr. Proctor studied the physics of jumping and the intricacies of ski technique, and although he himself never skied very much or very well, eventually he could teach a young man what he ought to know. Thus began Mr. Proctor's career which has made him known nationally as a ski expert and ski consultant. He worked out the best system for scoring jumping quickly and accurately and for reckoning points in meets. He has suggested improvements in the construction of ski jumps, and his initials are on the blueprints for the one in Hanover. Little do skiers realize that the form they use, leaning far out, like a bird flying, came to no little extent from his early study and advice to skiers.

Though he has served in many capacities, his typical position is director of officials at the Dartmouth Carnivals, and he has been in demand at important meets elsewhere, such as Lake Placid where he was chairman of the Olympic Games Ski Committee in 1932. Unquestionably he has been the most important man in the Dartmouth Outing Club for the last decade, and he is now chairman of the board of trustees. His views rather than those of a half dozen or eight other well-wishers are sought first on any new venture. In a club so large and varied in its personnel squabbles are inevitable, and Mr. Proctor is known for his tact in straightening them out.

Go to the top of Wilder where Professor Proctor has an office and you might think that you were somewhere else, for the books on the theory of heat, including: elementary kinetic theories of gases, matter, thermodynamics, and the theory of: heat engines are no more in evidence than books on the diffraction and interference of light and treatises on applied and physical optics. Such textbooks have their place, and their place is a little off right center where the illumination from the windows looking down on Richardson Hall do not throw them into prominence.

Too MANY AT HOME

What does hit the eye, even if it is unornithological enough never to follow the flights of übiquitous English sparrows, is photographs of birds. These are not just pictures of birds like robins, song sparrows, barn swallows, and purple finches—all very good birds in their ways, cocking their eyes for worms, or singing on a piece of grass, or twittering on the rafters over cattle, or driving the males from their perch where the sunflower seeds are (the female purple finches have as atrocious manners as exist in birddom), but rather close-up views, and remarkable they are also, of blue herons standing about doing whatever kind of thinking they do when they absent-mindedly tuck one leg up under themselves and forget to lower it for hours at a time. There are stunning pictures of duck hawks from Holt's Ledge. One may say quite simply about the duck hawk pictures that they are considered by those who know to be the finest collection in the United States.

"I had so many bird pictures at home," Professor Proctor explains in his mild and factual way of expressing himself, "that I had too many for Mrs. Proctor, and so this is what you'd call the overflow."

Later on you ask him if he has a great many pictures of birds, and he has already forgotten that from the point of view of at least one Proctor he has a great many, and he replies without prolonged cogitation, "Oh, no! Not many. Oh, yes! I suppose quite a few." Then allowing for relative standards he bethinks himself and enlarges the point of view. "Well, some might say I had a lot."

Numbers of course mean nothing to an expert photographer. Mr. Proctor talks rather in terms of time and equipment like range finders which he built before they were on the market and blinds into which he crawls at 4:30 in the morning and stays all day waiting for that perfect shot that delights even the bored specialists of the Leica Company who sent on to Mm a check for $lOO for a picture of a duck hawk. So extraordinary is it that people who see the picture in advertising leaflets know what kind of a camera they want to buy because they believe that the lens must be everything. They do not stop to focus their mind on the quality of mind and imagination, the perseverance, the skill in a professor of physics who also loves birds, enabling him to photograph a duck hawk in its tenderest moment, feed- ing its babies.

"I was interested in birds back in the 1880ties," reminisces Mr. Proctor. "I became interested in bird photography about 1900. About 1914 I began to learn a little something about birds and about taking pictures of them. I have never been free from intermittent spasms of working in the field of bird photography."

That is the way Professor Proctor uses English and understates. He says, "Duckhawk photography—that's my way of going fishing," but he goes no farther than this by way of verbal embellishment.

There is evidently much more to the story if one wants details, and they concern the long hours which Bill Ballard '2B, Hobart Van Deusen '33, and Dick Gerstell '33 worked on the blind at Holt's Ledge to the east of Lyme. They concern the collection of eggs Mr. Proctor has made, good enough not merely to be willed to the College Museum but also eagerly sought after though he has not had the time, or, as he might say and say wrongly, the energy to keep it up. They concern getting on the job at Holt's Ledge at 4:30 in the morning and hiding in the blind all day. They concern taking photographs at frequent intervals from the time the egg was first hatched 011 May 28th until the young duck hawks became big enough to leave the ledge on July Bth.

The pictures of gannels made on Bonaventura Island off Gasp 6 could be taken only after the same kind of pain-loving efforts.

Yet no one, not even William F. Russell Jr., son of the Columbia University Dean, who came to Dartmouth because there were more hawks near the campus here than there were anywhere else in the United States and who has written a learned book on hawks, would refer to Mr. Proctor as primarily an ornithologist. He is one, of course, but he is much more. Primarily he is a professor of physics. As director of the coordinating course, he deals with the historical development of his subject and he introduces his students to a detailed study of important experiments and theories in the various branches. In its nature this is a comprehensive course and serves as a general review of work taken in previous courses and as a means for giving a student a chance to orient himself and to derive a better understanding of the field of physics as a whole and of the philosophy of the subject.

As a physicist, Proiessor Proctor intet. ests himself more in the theory of light in which he gives two-semester lecture and laboratory courses, and heat in which he lectures and holds recitations for one semester.

His vocation and his avocation he com. bines neatly in a course called "Principles of Photography" in which he accepts only those students who have had a year 0F physics and elementary chemistry. Though it is not primarily a course in photo, graphic technique, a student learns fast enough how to take a picture and to develop it, but the chief emphasis is put on the principles of design and the construction of photographic lenses, the nature and character of photographic emul sions, and the principles underlying the various photographic processes including photographing in natural colors and photomicography.

Like so many good teachers, Professor Proctor has little to say about new-fangled pedagogical theories. So often it is the nonentity who attends educational conventions, dreams his way through interminable addresses, and talks with the seriousness that is his if not the light touch about texts and classroom methods. A good tennis player after he has played some years gets the feel of the racquet, the sound of ball on gut, and the rhythm oF stance and bending of body into the swing. He does not like to make a slowmotion picture of himself by way of illustration; he wants to play the game. So it is with the professor who knows his subject and wishes to communicate it. If yon press him hard enough, he might be able to tell you a thing or two about tricks to catch the attention and to goad the sleeping mind into action, but he would rather not.

Mr. Proctor would rather not. Self-itprecatingly he remarks that he has no A ucational theories worth expounding. lithe first place he teaches semi-advanced courses in physics, which means that the undergraduates take them because the like them and not ordinarily because the can ask a question or two during tb semester, come around for a confer®' during the apple season, and be sure ofcourtesy C. In the second place he taugfor two or three years in summer schoowhere no amount o£ educational then, could overcome the lethargy, the dullness and the fatigue settling in great fog banks over the Missouri minds that could not be shown. The sight of acres of bespectacled school teachers trying their damndest not getting anywhere tended to arouse Professor Proctor more curiosity divine teleology than human pedagogy.

Self-deprecatingly also Professor Proctor lays no claim to being a producing solo' He has had too many irons in the fire, he says with disarming frankness, too many ommittees to sit on, too many friendships to keep in constant repair, too many sports to follow, and too many trips to make about his New England.

"So I have not made a name for myself in the world of physics," he says, "but I realize that work of the Athletic Council even over a 22-year period and on the Dartmouth Outing Club Council for a number of years is not excuse enough. I simply have not had sufficient urge to do research."

But Professor Proctor has done research, no matter what he says. There is first of all the position he had during the summers of 1914 and 1915 with a concern develop ing technicolor, a technique which got hung up on a peg during the First World War and was begun later. He was chiefly concerned with a kind of prism enabling one to separate the object viewed into two portions and to get two pictures at once, and he had charge of fixing all the prisms in a laboratory in Boston.

"It wasn't very difficult," says Mr. Proctor, "but a bit fussy."

Yet it may not have seemed so easy to the owners of the business, who had no one in the laboratory who could do this job and who had therefore to import a Dartmouth professor from back in those there hills.

Later in the War he served in the Signal Corps Bureau of Aircraft Production in Washington. The meticulous technique that the Nazis have developed in war photography was during 1914-1918 something new, and the Dartmouth professor gave the government the benefit of his experiences with lenses and light. In an official and secret role he went to France as the trusted representative of the United States to observe how far the French had proceeded in war photography and to make reports on new discoveries in equipment.

And then there is the matter of the retina. Few men about Hanover, even those well informed, know how intimately and effectively Professor Proctor has been associated with the Eye Clinic and the development of the department of Physiological Optics. The story goes back a long way, to 191 a, when he was doing research in aviation at Harvard. There he met a man who interested him, Adelbert Ames Jr., with a mind showing a highly developed curiosity.

Mr. Ames was a person who had a considerable artistic flair and had in the beginning devoted himself to painting, but he found out that almost anyone could paint but few could understand what was the relation of the objective reality that vas bought they wanted to put on canvas and the subjective impression which made every man see form, light, and color terms so different that every picture had ecessarily to be unique. Mr. Ames's assumption was that a knowledge of the nature of the image received by the human eye would be of aid in suggesting how the various parts of a picture should be painted to give a pleasing and artistic effect. He was puzzled about the relations of photography to art.

Concerning these matters Mr. Proctor had a lot to tell Mr. Ames, and the two became friends. Del Ames, intrigued by the vastness of the field he had opened up for himself, went on to the Eastman Kodak Company, Clark University, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, and Columbia, and there he pumped questions at the experts who were not able to answer anywhere near all of them.

Mr. Proctor had seen that this was the sort of mind which could do well at Dartmouth, and he suggested to Mr. Ames that he try the Hanover air and the physics laboratory. Mr. Ames, who then had the

traditional Harvard point of view about Dartmouth, almost decided that he would not allow the granite of New Hampshire to ossify his muscles and his brains, but he came because of Mr. Proctor.

From 1919 on for the next four years the two men worked on the nature of the image formed on the retina, and then Mr. Ames joined the faculty. He hardly believes he would have reached goal after goal without Mr. Proctor's straight think ing and his rigid and accurate methodology for checking and interpreting results in advanced research.

The way these two research men talk about each other's work and their own contributions is refreshing.

Says Mr. Ames: "Charles is not only a straight thinker and a terrific worker; he is also one of God's great gentlemen."

Says Mr. Proctor: "I collaborated with Del for two or three years" (actually it was ten or eleven) "and I was too much interested and got away from my own problems in the classroom, and so I had to stop. I have too much of a one-track mind to let myself get too deep in problems away from the curriculum."

This is his way of putting what seems to be a fact, namely, that the two men worked like dogs and even slept in Wilder Hall rather than go home.

Though Mr. Proctor is now 62 years old, he is still the best all-round athlete on the faculty. In keeping with his versatility in sports, he plays golf and began the game during his senior year at Dartmouth. At Missouri he had to give up his beloved tennis because the courts were made of cinders—a devil of a surface, to put it bluntly. There he went ahead knowing nothing about golf strokes and forming for himself, if one may believe him, a series of faulty motions which he has had to fight against ever since. He dropped golf ten years and then he took it up again in Boston in 1914. That is the way Mr. Proctor's golf game sounds when you talk with him.

I£ you talk with someone else, the story takes on a different color. Dean Bill says that he would rather play with Mr. Proctor than anyone else he knows, for Charles has his temper under control and has a generous spirit in competition that must at the least be called unusual, no matter hqw he hooks and slices. He used to be at the top, and some years ago he was state champion, but a series of illnesses, an operation and a pneumonia, set him back, but not for long. He is playing now well enough to talk in terms of the high seventies or on bad days in the low eighties, which is far from being washed up. Plenty of men about town wish they could just for once in their lives say they broke 90. Mr. Proctor often plays with Dean Bill, Prof. Leslie Murch, and Prof. Fred Longhurst— all first rate golfers.

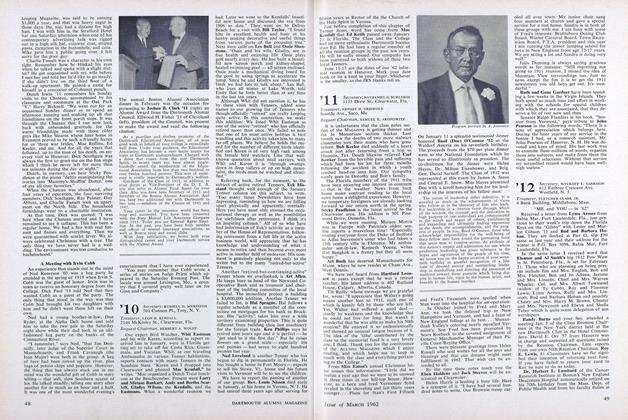

President Hopkins and Mr. Proctor have for years been frequent golfing partners.

Tommy Keane, Hanover golf pro, when asked if he could tell something about Mr. Proctor's golf said: "Well, I can tell you some damned mean things Mr. Proctor has done to me on the golf links."

Tommy gives Mr. Proctor four strokes these days, no more. "He's the damndest man to beat as ever I see," says Tommy decisively. "I sure like to beat him, and he sure likes to beat me."

He describes Mr. Proctor's game as "consistently straight, always down the middle. His game excels from 100 yards into the green and is really something to talk about from 50 yards in. When you think that he is licked, he will all of a sudden sink a chip shot."

When the golfing season is over, one may find him of a late afternoon at the Graduate Club shooting billiards with Paul Sample '20, Dr. John McKenna, Harry Hillman, or Fletcher Low '15.

One has not yet exhausted Professor Proctor's hobbies. He likes to bowl, and if you ask him about it, he admits to doing "fairly well." Actually he is rated among the half dozen best bowlers in Hanover, and in practice he can always hit 90. In competition he is apt to do better, as one would expect, and in tournament matches one year he averaged 96 throughout the winter.

Add to Professor Proctor's accomplishments the art of cabinet making. When he left the army, he got a bonus of $6O, and he spent the entire amount making a billiard table using slate from an unmentionable source which did not cost him anything— the cushions, cloth, and balls used up the money. He did not have to pay anything either for the scrap lumber used for the table itself.

ONLY "PRETTY FAIR"

"It was a pretty fair table," says Mr. Proctor, who is fond of the words "pretty fair" when describing anything concerned intimately with him that he does very well, "and I used it a lot." As books began to pile up and weigh down the attic, he had to dismantle the table, for with the special slate it weighed 400 or 500 pounds, and he began to be afraid that everything would go crashing down from the attic into the cellar.

Mr. Proctor's activities being what they are in intensity and range, he simply has not had the eyesight or the energy in the evenings, even though he is a professor, to read much good literature. "I read only trash," he says without apology. "I want light reading after dark." But he admits that once he read much that was serioushe used to be a Kipling fan; Whitman too he read; and he used to—this is his way of saying it—"spout" poetry. At one time in his life he could quote all or almost all of Omar Khayyam. John Buchan he has not forgotten: he liked him so well that he read everything he wrote through several times.

He has been abroad three times, but he does not talk about Europe in a way to make one think that Europe has had much effect on his thinking. When a sophomore in Dartmouth, he went first with Dr. Frederick Lord '9B to England for a bicycle trip. In the spring of 1918 he went over to study aviation war photography. On a sabbatical in 1933 Mr. Proctor went over again, spent some time in Germany, and toured with his younger son, John, Dartmouth '36.

Traveller, sportsman, committee man, ski expert, research scientist—Mr. Proctor is all of these, and yet primarily he is the teacher. No one should know better about his standing than President Hopkins, who travels the length and breadth of 4 United States year after year, and he js convinced that Mr. Proctor is a superbly good teacher because over and over agaj,, alumni direct questions at him about Mr Proctor, not perfunctory inquiries, but in timate and searching questions showijo that the askers are sincerely interested and have been much moved by his spirit in the classroom.

If he is primarily the teacher and a su. perbly good teacher, it can be only because he is in essence a human being, intelligent and sympathetic. The best of the fen stories told about Mr. Proctor belongs to President Hopkins.

During the War, Secretary Baker wanted Mr. Hopkins to travel as much as he could in order to be in touch with conditions and so he furnished him with passes for army planes. Mr. Hopkins had never been up, and he awaited with keen anticipation his first ride with the Potomac Patrol pro. tecting the Capital, called euphemistically the Training Patrol. An attractive young officer flew him 75 miles down the Potomac and back in a flight completely uneventful. Upon returning to Washington Mr. Hopkins described it nevertheless with glowing enthusiasm and at great length to Friend Charles who was as interested as if he had been along also.

On a later occasion at Langley Field the pilot of a plane said to Mr. Hopkins thai he was not sure he would be willing to tale him up because he had almost killed a member of his faculty, Captain Proctor. The pilot explained that they had gone up several thousand feet on a gun-testing flight and that the plane had plunged to what looked like death.

And so Mr. Hopkins discovered to Ms chagrin that Mr. Proctor while listening to his story about the uneventful flight down the Potomac had himself been flying often on dangerous test experiments and had nearly been killed in one of them. The more Mr. Hopkins thought about this, the madder he got. When he attempted to blow up his friend he was amazed to find that Mr. Proctor had been sincerely interested in his Potomac flight, that Mr. Proc tor was surprised to find him annoyed, thai Mr. Proctor had not considered his own test flight important, that after all nothing had happened beyond the plunge. And so Mr. Hopkins came to realfze that CharleProctor was modest to a degree rareh found in men, that he had not been in the slightest conscious of any dramatic effect in keeping silent, that least of all he trying, tongue in his cheek, to draw Mi Hopkins out.

Any one of Mr. Proctor's friends would agree that if it is rare to find a universal man in a specialized age, it is even rarer to find a man so gifted in his special fieldan, so richly endowed in his avocations who is also genuinely simple, modest, and human

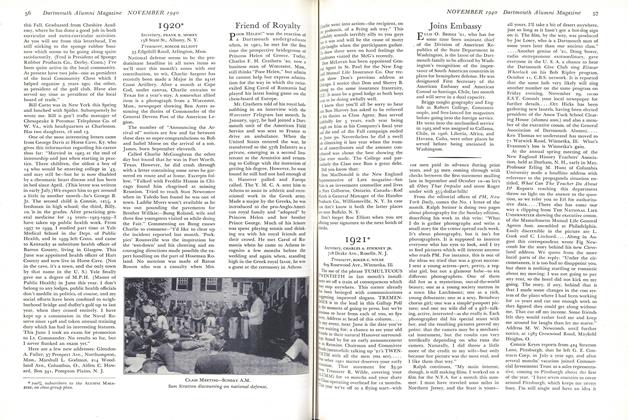

CHARLES PROCTOR POSES WITH HIS TEAMMATES IN 1900 Dartmouth's First String Football Players when Proctor was a Junior. Top Row: Corson'OO, Stickney 'OO, Boyle 'OO, Low '01, Rogers '00; Second Row: Ailing '02, Proctor '00,Wentworth 'OO, Jennings 'OO, Whalen 'Ol, McDavitt 'OO, Manager; Front Row: Farmer'03, Crowell '01, Gilmore '01, O'Connor '02.

FATHER AND SON Left to right: Charles N. Proctor '28,Charles A. Proctor 'OO, and German Raab,ski instructor, shown a dozen years agowhen the wearer of the "D" above was captain of winter sports and champion skijumper. Young Charles has an historicDartmouth lineage going back to his greatgreat-grandfather, Ebenezer Adams of theclass of 1791.

OLD FRIENDS ON FAMILIAR GROUND President Hopkins '01 (left) and Professor Proctor '00 are faithful members of the"Sideline Coaches Club," often following football practice on Memorial Field together.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCan I Get In?

November 1940 By COREY FORD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926*

November 1940 By CHARLES S. BISHOP, CLARENCE G. MCDAVITT JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

November 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

November 1940 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CRAIG THORN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

November 1940 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ROGER C. WILDE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919*

November 1940 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, JAMES C. DAVIS

JOHN HURD JR. '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleOn January 11 a splendid testimonial dinner

March 1962 -

Article

ArticleSome '71 Statistics

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleWYMAN TAVERN, THE INN AT KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE IN WHICH WAS HELD THE FIRST MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1920 By Elgin A. Jones '74 -

Article

ArticleAnother Sgt. York

October 1944 By Ivan H. Peterman -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1965 By LARRY GEIGER '66