Non-Academic Creative Activity in College Ties Body and Mind Together, and Touches the Soul ALLAN MACDONALD ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

DISTINCTIVE AMERICANS have always been suspicious of our educational policy. Their suspicion has had a constant center in the belief that education is too distant from living. When Emerson declared that "books are for the scholar's idle times," he was not only speaking as a belated Romantic, he was declaring himself an American. America was fashioning not only a democracy, but a new way of living. The aristocratic sanction for European education no longer held here, though our universities kept on in their imitation.

Since the culture our colleges inculcated had little meaning to the graduates, they went forth to forget that culture, and, too often, to make a fortune against society. They became wolves in sheepskin clothing. Or, if they followed the culture, they became clergymen and teachers, divorced from physical reality and tolerated by their classmates as goats sacrificed to propitiate the gods. Something was wrong, but the educators remained loyal to their choice and imposed it on the new generation with the righteousness of Wheelock drilling noble savages in Hebrew. Rather than create a more living culture and meaningful education, they backed step by step before the demand of the student who wanted something "practical and useful and modern," and got only a new set of abstractions, though they seemed to have more to do with society and men.

Left to himself, however, the student discovered extra-curricular activity, which, I suspect, is America's only major contribution to education. In an artificial world where everything was done for him and was driven up into his unwilling head, the undergraduate found his own escape and his own action. As the mere task of living, of carrying water and wood and of supporting oneself in New England became easier and college life more liberated from physical need, the energy flowed over into play and work outside the course of study and finally rivaling it.

For a long time most of us teachers have decried these activities. I, for one, have repented. They seem now a healthy attempt to find something to do with men and functions, some relationship with the physical universe. The difficulty is that most aren't worth the candle. The desire is good, the means inadequate, and the possibility of continuance small. Yet, since college men had no other means, they have given glory and precious time to campus activities. The glory betrayed them, for it limited the spread of responsibility and it fostered a narrow politics.

It is foolish to suppose that the undergraduate knows what he should have. Such a supposition denies the very value of education, which works with men who are becoming, and who are only growing to love worthy things and noble action. Yet, if their activity is the outward sign of a deep and unsatisfied need, we must recognize its urgency as symptom. This we have not done.

BODY AND MIND TOGETHER

It is not my right here to advance a system of education, but it must be obvious that such a process of growth should have within it a directed fulfilment of youth's tremendous energy, some possibility of acquiring a skill that will carry over into post-graduate life and will bring body and mind together after their separation by the Puritan and by the sport enthusiast. Since boys are now kept from productive activity at home, relieved of all responsibility for soul and body, and kept in prolonged immaturity, it becomes increasingly important that they find something at college beside the sport and study which divide their day but do not enrich each other. The problem is too fundamental and too large to find easy solution within our present philosophy of education, but there is the restless shimmer of a new dawn on our horizon, and it is not Aurora but Dean Bill who is bringing up the sun.

I have said that the students have found their own way in some instances. TheDartmouth makes daily boast of its long life. The Outing Club is everywhere respected. The Players and Jack-o-Lantern have a large alumni family. The merits and faults of such groups are familiar. Newer compasses, corrected to our day, point more insistently toward our true North. Quietly, and suspicious of fanfares of publicity, ventures in education have been setting forth. There is a great faith behind them, but a right fear of laying down single routes and ends, for the machinery of means is less than the men who will use the means to their own fulfilment.

One does not know where to begin in comment on this young brotherhood of projects. There is the Experimental Theater, under Theodore Packard, with its courage to risk failure by experiment and by widening its use of workers on and behind the stage. Yet, because of its freedom from box office pressure, the group has enriched the pleasure of the community immensely, while it has also let men learn by doing. There is the Prokofieff Society with its engaging quality of delight, "amateur" in that fine sense that has been corrupted from loving to incompetent, but which the Society is restoring. These groups have won their applause by public performance. Others are less "familiar because their function is less public.

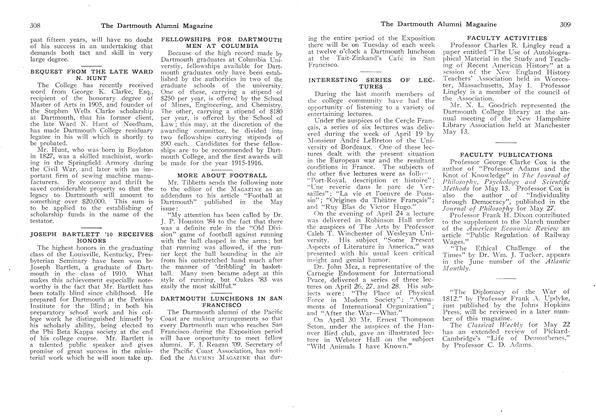

Dean Bill has been calling men here to work with students, and has found the right men, which is the real secret of such an experiment. One of the first comers was Ray Nash, who set up shop in the Library and vivified dull signs and bookplates and notices with honest design. Under him boys have set up and printed their own and others' verse, Christmas cards, bookplates, personal marks, etchings. They have seen him turning off his own work and, perhaps, heard his lectures on graphic design and book making. The printer's product is one in which poor craftsmanship betrays itself, and men who have worked under Nash must gain a sharpened visual awareness and a deep respect for good work. Conceit and artiness cannot endure under the discipline of printing and the spirit of The Graphic Arts Workshop.

In Wilson Museum Prof. Bowen and Dr. Denison helped men to work in entomology, ornithology, and palaeontology. Students make their own collections, classify arrowheads, patiently dig fossils out of their plaster jackets, train themselves in skeleton classification, or elect some other experience in a technique that interests them. The Museum has grown so energetically under Prof. Bowen's care that a dozen fields offer themselves to eager fellows. A good many of them go on to further work, and, whereas most of us get only a Christmas card from old students, Bowen may get a box of insects. Probably few of the alumni realize the richness of the material displayed in the Museum and the amount that awaits only equipment and room to be shown.

Next door Dr. Richard Weaver has turned the old Dragon house from a tomb into a workship. Despite his modest disclaimer of control over nature, many a Hanoverian will swear that he attracted flocks of birds to our town. Wherever one looked last winter he saw a Purple Finch or an Evening Grossbeak boasting a gailycoloured ensign on the stern. They had been trapped and banded or presented with this gay telltale. With Weaver boys are making bird censuses, bringing in lists of flora and fauna, banding birds in the college park and other places about town. Groups of students and of townspeople and faculty go out twice a week to observe and quicken their eyes. Club meetings bring together the confirmed naturalists and the new men who will carry on their work and get roots down into this soil.

PAUL SAMPLE, ARTIST

In Carpenter Hall Paul Sample holds an afternoon painting class and an evening life class once a week. These are in addition to his primary function of artist in residence, which, I take it, is to demonstrate that a painter can be one of the finest chaps going and that art is not a completed product reproduced in a book, but-, is an activity, something done with body and spirit. There are only four or five such artists in residence in the United States. It is not easy to find a recognized painter who has the generosity and patience and skill to be a good teacher. Dartmouth can congratulate itself, for Mr. Sample is awakening students to the miracle of the human body and a keener vision of relationships of color and form in nature. Most of all, perhaps, he stands as symbol that the critical mind of education does care for the creative faculty on which it must live. For too many centuries the academic and the productive have glared in hateful suspicion at each other. The blame rests most heavily on education, which is necessarily conservative, and it is good to feel that a creating artist is welcome here.

Under Mr. Delahanty's enthusiasm there is taking place a quiet revolution in physical education that puts interest before perspiration. So long as educators respected only abstract knowledge they insisted that physical exercise be only an expense of calories. Now Dartmouth, far ahead of most colleges in this, is releasing from the usual competitive sports those men who are so vigorously interested in some activity that they take the initiative in proposing its acknowledgment. So today you may find men sailing dinghies, paddling canoes, banding birds, practicing winter sports, cooking out of doors, and incidentally, receiving recreational credit for it.

In the country around Hanover a group of freshmen and sophomores are training themselves in the qualifications of a Junior Guide under Ross McKenney. They practice woodcraft from cooking to making fish traps, from fire prevention to tying trout flies. In the workshop under the Outing Club they make skis, or packs, or buckskin shirts.

Somewhere in the offing is a large workshop equipped with power tools where men will be able to satisfy the old desire to make something they can see and use. If the students are able to fight their way through the line of faculty which will crowd into the shop, they will have a good time.

These activities are going on so quietly that alumni and faculty are hardly aware of them. If they are, they may see nothing unusual. Yet, closely scanned, this widening of extracurricular activity under expert guidance, conceived in terms of joy, knowledge and continuance of interest beyond college, is markedly progressive. A decade ago tennis and golf were the only sport activities that promised a future, and writing and acting the only professional kindergartens. Old campers and Boy Scouts and products of unconventional schools and backgrounds were left without furtherance of their skills, except as they found time to train themselves, and other men had no way of finding a form for their vague desires. Now there is this new attempt to foster the whole man and bring him to happy harmony.

Study is not enough for any man, most of all a growing man. Nor is ordinary sport, culturally so sterile, balance enough for many men. Work and creation must balance bookish study before we can believe the college's work best done. But men look in vain for a major change and a great overturn of present organization. If, however, they look about them, they will see the change slowly happening, but experimentally and unobtrusively. The great virtue in these trainings is that students work under men they like and respect, and they work with materials not so easy to persuade as a classroom teacher. If they have had a big-frog-in-little-puddle success at school they learn humbly that they have been carrying more sail than their ballast allows, and that only hard work avails. If they have had only the wish to work in some medium, but have been stopped by lack of equipment and direction, they now have their chance. The whole process is one of growth in respect for work, for stubborn materials, and for achievement. The end cannot be reached by packing a diploma away in the attic. A man either quits with a generous recognition of the ability of others, or he goes on trying to make himself a more creative man. and that is a life work, and the only one.

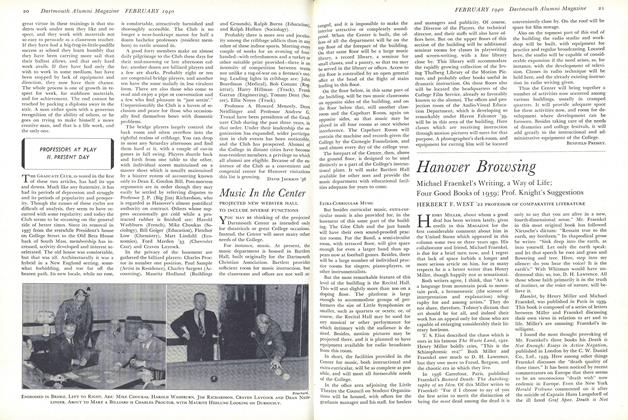

Views of activities in the creative and manual arts program without academic credit,for interested undergraduates. Top left, student worker at a lathe in the ThayerSchool workshop; right, naturalists arebusy every day under guidance of RichardI. Weaver. Center, left, Mr. Weaver instructs a group of student naturalists in thefield; right, Paul Sample, artist in residence, shown with an informal undergraduate class in sketching and painting. Bottom, left, Ross McKenney, woodsman andguide for the Outing Club, with outdoorcandidates for his expert guidance, and right, he directs indoor class.

PROFESSORS AT PLAY11. PRESENT DAY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMore Than Professor

February 1940 By JOHN HURD JR. '21 -

Article

ArticleThe College In The Sixties

February 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

February 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

February 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1925*

February 1940 By FORD H. WHELDEN

Davis Jackson '36

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleHanover Personal

November 1938 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleHanover Personal

January 1939 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleCraven Laycock '96

February 1939 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleProfessors At Play II. Present Day

February 1940 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth in T. V. A

October 1936 By Davis Jackson '36, William P. Kimball '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleFELLOWSHIPS FOR DARTMOUTH MEN AT COLUMBIA

June, 1915 -

Article

ArticleMEMBERS OF 1924 RECEIVING SCHOLARSHIP HONORS

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleSCHEDULE of EVENTS, ALUMNI CARNIVAL, Feb. 22, 23, 24, 25

February 1934 -

Article

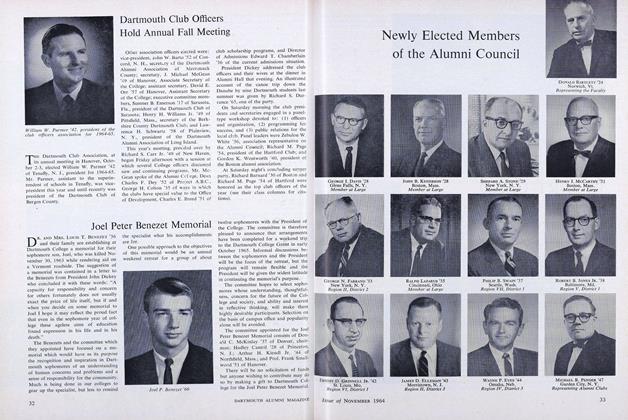

ArticleDartmouth Club Officers Hold Annual Fall Meeting

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleCONTEMPORARY RELIGION

January 1933 By Boynton Merrill '15, D.D. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1960 By EDWARD S. BROWN '35