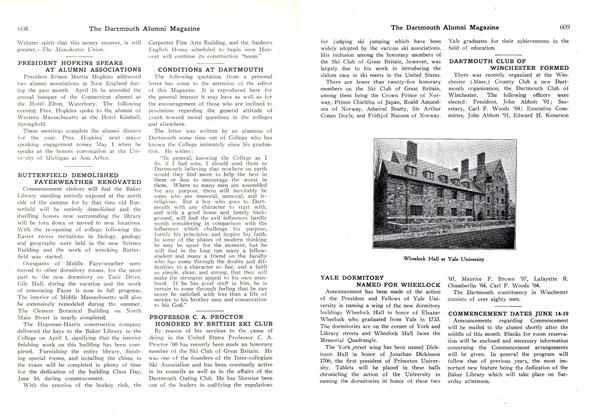

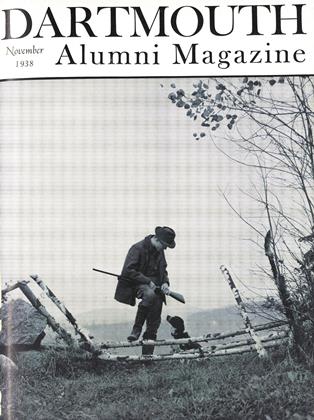

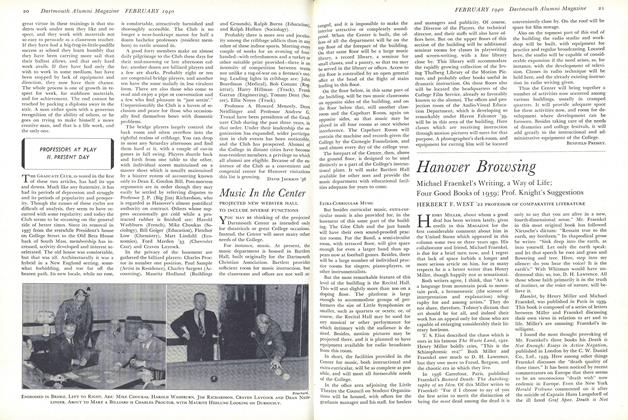

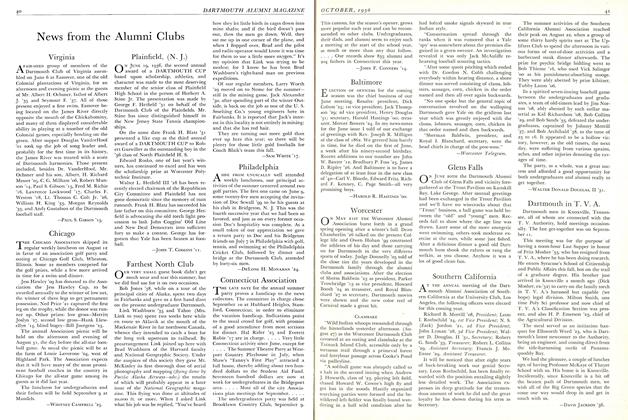

INSPECTOR BRAY, CAMPUS COP, BETTER AND POPULARLY KNOWN AS "SPUD"

ONE NIGHT IN the year 1888, a fourteen year old boy in Salem, Massachusetts, quietly gathered together a few belongings in his room, saw the coast was clear and dark, slipped silently out the window into the wide world to seek his fortune. George Chase Bray was tired of Salem, and wanted to be on his own. He found his way to Portland, Maine, and for eight long months his mother and father were ignorant of his whereabouts. When he was finally located, he had determined not to come home, for the world was big, and a lot of fun, and he had a job selling papers, sandwiches and cigars on the railroad. For four years he plied the bumpy, mountainous route on the old Maine Central from Portland to Lunenburg, Vermont, and then was promoted to brakeman. Those were the days when a brakeman's job was man-size, and you had to perch outside over the grinding trucks and turn the big wheel around and around by hand.

George Bray was young and vigorous and patriotic. When the Spanish war came, he belonged to a company of the- national guard at Skowhegan. They weren't moved fast enough for him, so he joined an outfit at Rockland, and eventually landed at Chickamauga Park, Georgia. Detailed to the military hospital, he fell sick with typhoid fever, and was laid low long after the close of the war and after his mates had all gone home. Those were dull and unhappy days, and he was twenty-four when they let him go back home to Salem—ten years since he had run away.

A year at home and his strength regained, he felt the wanderlust again. This time it was New York—the New York of the nineties, greatest and most exciting city in the world, a far cry from Portland and Lunenburg. He found his way into a job as inspector on the old Second Avenue trolley line, and rattled his course up town and down town for five years.

It was in New York that he met Minnie Buskey, of Vermont, who became his wife. They lived in New York until the city lost its novelty and charm for them, and they began to think fondly of the North Country.

One night Bray picked up an old farm catalogue, left in a trolley seat by a passenger. Thumbing idly through the pages, he ran across an advertisement of a farm for sale—a "fine profitable farm"—in Sharon, Vermont. He took it home and showed it to Minnie.

They made the long journey to Sharon in the dead of winter. All they could see of the farm, unoccupied, was what rose above the height of drifted snow. It was bleak but solid. A neighbor said it was a good buy, and they moved in.

A year and a half of the farm was enough. The land was poor, the product small. They both worked, but times were hard, and in that year and a half they found themselves uncomfortably near starvation. That August they started in a buggy toward Lyme, where Mrs. Bray had relatives. George stopped in Hanover to water and feed the horse, and struck up a conversation with Doc Woods, then head janitor for the institution that was, George learned, Dartmouth College. Before leaving for Lyme, he applied to Mr. Gooding, Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, for employment. He was hired, and reported to Jake Bond, head janitor.

That was August 11, 1920.

Today, George Bray, affectionately known as "Spud," by five thousand latterday Dartmouth men, lives serenely with Minnie in his neat, green and white farm house just above Lyme. He still works half time, but a new man is being groomed for the work in anticipation of Spud's retirement. If you want his story first hand, you can see him there, busy and healthy, confident that life is a pretty good business. If you can get him started, he will reminisce about the College, its growth, its personalities, its lore and tradition. Spud is, himself, well on the way to becoming one of Dartmouth's legends.

He's had a real career. His first work was moving furniture, when three men and a team were the whole works. He cut clover for the guinea pigs and mice used by the Medical School. He took tickets at games. He got every odd job in the College, and fast became a familiar part of the Hanover scene.

He was made janitor of Topliff Hall the year it was built, and struck up his friendship with Lloyd K. Neidlinger, sophomore, and Robert C. Strong, freshman. From the unofficial deanship of Topliff he rose to night watchman, head janitor, and finally College Inspector, the College's one-man police force and riot-squad combined.

He fondly remembers the days when Dartmouth men were rough and tough and hard as nails—the days when freshman week was a week of hell and cracked noses, and the picture fight was a he-man's battle. He remembers the all-day war between the sophomores and freshmen when the freshmen appeared in chapel (then compulsory) minus hats and coats and neckties, defying the traditional rule. George is sure that the cracking of ribs and the blacking of eyes is a scene that will never be reenacted within Rollins' sombre walls. He remembers the hazing at the old watering trough at Main and Wheelock, and thinks often of Delta Alpha parade "when it was really good."

Prohibition was a trial for Spud. For a long time students regarded him furtively as the "campus cop," and it was with friendly reluctance that he would occasionally confiscate a bottle of dubious fire water, in the name of law and order. But they got to know him, and got to know that he was, in Hanover, a fellow's good friend in time of trouble. There are many youthful but serious misfortunes and mistakes which Spud has cleared up, and he has come to be known as supreme in the art of engineering young men out of jams.

"It's been a great life," says George. And he has a right to be satisfied. Pretty soon, when the new man takes over completely, Spud Bray will be a legend to the incoming classes. But for two decades of Dartmouth men he'll be an old friend, glad to see you and reminisce with you at his green and white farmhouse in Lyme.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1938 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1938 By "Whitey" Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

November 1938 By The Editor -

Article

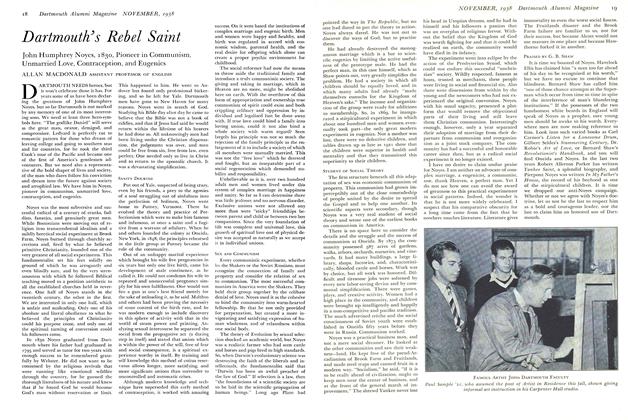

ArticleDartmouth's Rebel Saint

November 1938 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1938 By EUGENE D. TOWLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

November 1938 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.

Davis Jackson '36

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleHanover Personal

January 1939 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleCraven Laycock '96

February 1939 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleEducation Without Books

February 1940 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Article

ArticleProfessors At Play II. Present Day

February 1940 By Davis Jackson '36 -

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth in T. V. A

October 1936 By Davis Jackson '36, William P. Kimball '28