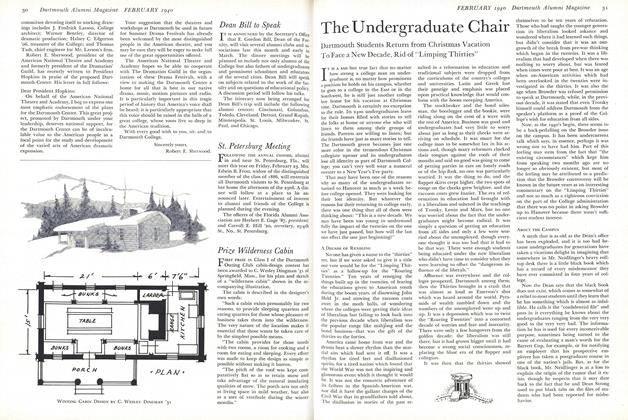

Undergraduates have seen a tall graceful Indian shoot from the center of the campus. They saw the monument of ice begin with a pile of snow, the scrapings from the paths of the college; they saw a maze of pipes interlocking to form the framework of the Indian and then watched it being coated with snow and slush. The Indian, shooting an arrow into the air, took six days to build and gave Dartmouth a small idea of the work and man-power which is poured into Carnival. Soon a rope will be thrown around the shoulders of the cold warrior and a truck will pull him down. The seven foot ice pedestal upon which it is standing will remain until it thaws and the only physical memory Dartmouth will have of the first carnival of a new decade will be a heap of melting snow around which it will have to detour when crossing the campus.

But before Dartmouth could enjoy its week'svacationandits Carnival, itspent two weeks in a glorified "Information Please" period. There were no prizes offered; no cash register bells rang and there were no Levants to hand out wise cracks nor were there any Kierans to give facts on everything and anything. This was a grim business, Dartmouth's two week period. It was all night cram sessions, hot coffee in paper cartons, chain smoking and finger-nail biting. It was walking to the gym with the roommate and trying to read him a few last minute facts from a crumpled sheet of paper which had been read and re-read but he could only hear you drone—the words meant nothing to him for he had his own piece of paper to study. Then it was sitting in one of the chairs in the section allotted to your particular course and waiting for the exams to be handed out; after they had finally come, there was a five minute period in which you were tempted to hand in your blue book and walk out of the hall. But somehow it was never necessary. The walk back from the gym was a funeral march and a postmortem. Then after exams were all over it was the long wait for grades.

Now they've come. There are a few faces gone from each class, faces which lived in rooms which are now bare except for a waste basket with a report card lying in it, face down. One of the saddest sights we have seen in four years of college was that of a senior about to leave college. He was standing on Main Street with a few of his best friends and they were grouped around him singing "We're glad to see you go" to the tune of the Farmer in the Dell. He was laughing, just as they wanted him to, but the singing was flat and his laugh was hollow.

During the examination period, 2400 students took a few more than 12,000 examinations and, if the estimates are somewhat near the truth, each man wrote 1200 words on each examination. All in all, Dartmouth sat down and wrote between 14 and 15 million words—the faculty had to read them.

There were questions to suit everyone's fancy. In one course, students were told that a bullet had been fired into an even date on the calendar and were asked what the mathematical probability would be of shooting out all the other even numbers. In another course undergraduates were asked to write an essay on a subject which most Alumni readers could discuss but perhaps not as thoroughly as this professor would require: "Give your supported opinion as to the adequacy of the Sherman Act and the Federal Trade Commission Administration as controls for dealing with the decline and disappearance of competition." Another professor asked his class what the objectives of President Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference were and to what extent they were realized.

But one of the most interesting questions among all those asked was one which had a story behind it. Shortly before the examination period began a member of THE DARTMOUTH board uncovered an ordinance on the books of Hanover which prohibited the distribution of handbills. Believing the law to be unconstitutional he went to Professor James P. Richardson of the Political Science Department and asked him his opinion of the ruling. Professor Richardson found the case so interesting he asked that he might be allowed to reserve opinion until after he had given his examinations in order that he might include it as a question. (It was included and counted seventeen points.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEducation At Its Best

March 1940 By ARTHUR DEWING '25 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

March 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleAn Obligation to Alumni

March 1940 By BEN AMES WILLIAMS '10 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

March 1940 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Article

ArticleThe College in the Sixties

March 1940 By DR. WILLIAM LELAND HOLT

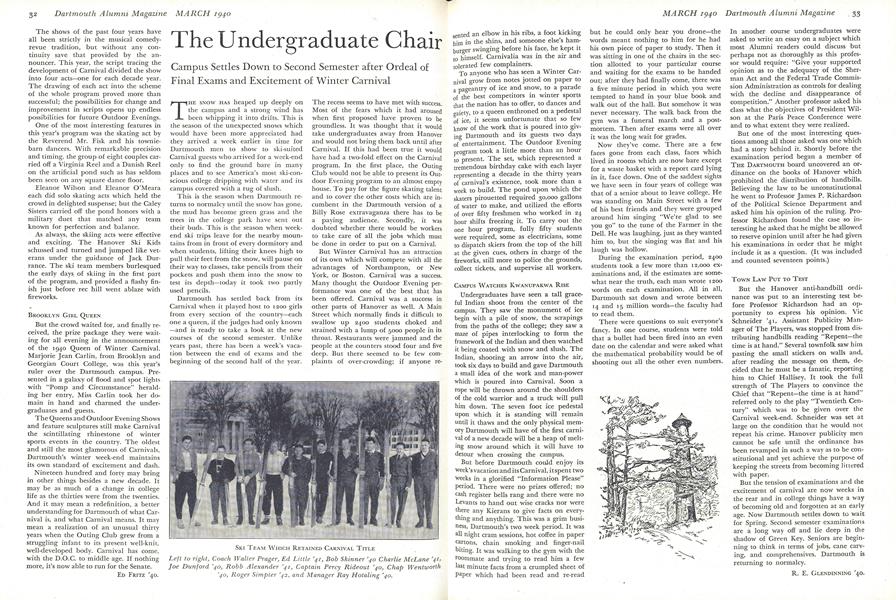

R. E. Glendinning '40

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

October 1939 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleCRUSADING SPIRIT WANES

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleABOUT THE CAMPUS

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleTOWN LAW PUT TO TEST

March 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW DORMITORIES

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleDEPARTMENT CHAIRMEN APPOINTED FOR TERM 1921-1923

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleA. T. O. CHARTER WITHDRAWN

October 1936 -

Article

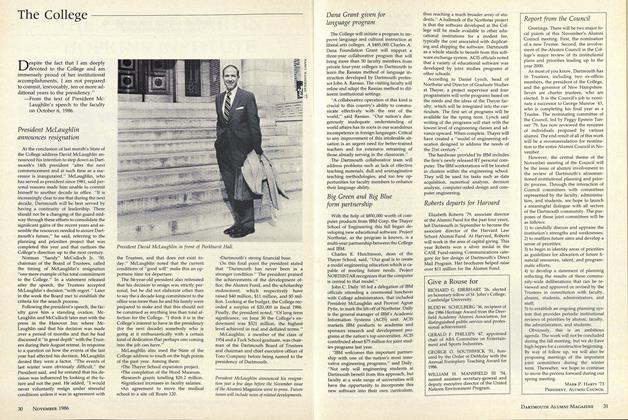

ArticlePresident McLaughlin announces resignation

NOVEMBER 1986 -

Article

ArticleFrom the Man Who Ought to Know

December 1992 -

Article

ArticleTesreau Memorial

July 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26