Early Snow Brings College Nearer to Popular Conception; Editor Doubts General Delight Over Wintry Days

THE SNOW IS FALLING, and it is true that there are about as many people grousing as there are rejoicing. Good alumni probably remember their college as the great center of winter sports, the home of the ski. This process of memory is a softening one, and every year the memory may grow softer, more idyllic, closer to the stylized or popular conception. Dartmouth to Joe Doakes means "snow": consequently as Joe Dartmouth becomes more and more Joe Doakes he thinks more and more of "snow" when he thinks of Dartmouth.

But how many of the snow-recalling Joe Dartmouths spent the winter afternoons in rummy? How many shuddered with the snow, turned up their coat-collars, and said, "I bet Dartmouth would be twice as popular if it was only in Florida"?

There are 1700 pairs of skis in Hanover. The statistic on how many pairs of skis get used only three times a year would doubtless be impressive.

In fact there is quite a little scowling and loose talk about the winter going on these days. Some seem to feel about snow the way Jurgen felt about the ocean waves: when you've seen one, you've seen them all. Winter's icy hand closes down on Hanover with a vengeance that reminds the undergraduates of how far they are mythically supposed to be from civilization. The reaction is either to jump into the ski-room and wax up the boards for the winter's sport, or to curse and head for the Nugget, the gym (a city-within-a-city these days), the bridge-table, or the day-bed.

When there comes a relaxing of the cold that bites the throat, and the crust corns and the streets run brown and muddy, then coats flap open and snowballs fly. After the opening basketball game they flew back and forth across Wheelock Street, at passing cars, at open and shut dormitory windows. It was one of those strange and sudden bursts of mob fever. Any man who broke and ran was a fair target for all hands. So $65 worth of windows were smashed, the Interdormitory Council decided to fine offenders $5, the Dean sent an angry letter, and The Dartmouth wrote an editorial pointing out the dangers of snowballing and the difficulty of not-snowballing:

"It is a small matter. But perhaps it is a nutshell example of what happens to great ideals, world-beatifying collective movements, self-conscious morality, even personal dreams. We can say, 'This is what we want'; and then we can wing another snowball and think, 'This is what we give ourselves.' "

A WAH-HOO-WAH: for Hugh Elsree's "American Student Morale" in the last issue of this MAGAZINE. Professor Elsbree has the answer to what's been bothering everyone about the degenerate younger generation. He says, with great candidness and not at all with the air of a man laying his head on the choppingblock, that it is largely the parents who are to blame for their sons' refusal to lend their seriousness to the world community. He says:

"For seven years, during which their sons have been at a far more impressionable age than when they come to college, the parents of most college students have been telling them that the United States is governed by a man who is or wants to be a dictator, that the Constitution has been destroyed, that the government has become totalitarian, and that our most sacred ideals have been trampled in the dust. And yet they cannot understand why some of their sons are slow to see in the present conflict a struggle between two sharply contrasting types of governmental institutions and ideals.

"They tell their sons that the less government there is the better, and then invite them to die for their government. They tell them people should not be allowed to have the kind of government they vote for, and then ask them to go and fight for democracy. They preach a brand of individualism that denies the claims of the mass of individuals, and then expect their sons to be willing to surrender their lives for American individualism. They condemn in the most vigorous language every novel governmental restraint imposed upon them, and then urge their sons to accept cheerfully and even enthusiastically the rigorous discipline of the training camp. They denounce as unjust taxes and borrowing for the benefit of the millions, and then expound to their sons the doct rine of sacrifice."

I remind you of all this in case you have forgotten it from last month. It is the kind of savagely unpleasant truth that is more comfortable to forget. Mr. Elsbree's paraphrase sounds like quotation from an average businessman-parent, translated into impolitely bald English. I've only heard of one father honest enough to say what he thought in such plain language: "I have to worry about these four walls. I'll leave the worrying about the world to you."

One thing is sure: so long as parents teach their children "to identify Americanism and democracy with the preservation of the economic status quo," those children aren't going to be anxious to do anything much except enjoy the incidental gravy that comes their way as beneficiaries of that status quo. I mean to say they won't be» crazy to make any gallant gestures (or even any life-saving exertions) that will postpone the transformation of Joe Dartmouth into Joe Doakes.

The discussion is a little tenuous right now, when we are in one of the regular troughs of the excitement-about-the-war cycle. There are cheers for the Greeks, very little shouting about "keep us out of war," not much activity on any front. One of the students back from his month's Naval Reserve cruise says that he thinks the V-7's really had a bad time of it with the deadly standing-in-line military life, but that when they got back they decided they had done something great for their country and therefore reported the cruise was splendid. So you see how it is: very few are anxious to fight; most are willing to do it because it seems necessary; already the dishonest Pollyanna-propaganda is having its way with men, to make them kid themselves into thinking war and war-games are not just essential for preservation but are also fun.

With a decided change in the course of the war the student temper will change too. Meanwhile it's a good idea to remember that vague references to "the youth" refer to nobody, because different youths are different people. Meanwhile also it goes on being true that many a Dartmouth student "wants to find justification for the ideas he has embraced. He wants conviction, not knowledge." Undoubtedly Professor Elsbree deserves lynching for being a damned Communist and pointing out all these un-American truths. All I ask is that I be swung from the gibbet nearest his.

The Campus Cafe is closed for good and "the unsophisticate bad-food restaurant" days of Hanover are gone. We are all efficiency and a nickel extra for jam these days. George Gitsis has nothing to do and the most ghoulish scene in this Suburbiadecorated pre-Christmas Hanover is the row of falsely cheerful colored lights strung up the dark Allen Street side of the Sunny Corner. Eating is no longer an adventure but is reduced to a business. Where are they now, the happy ones who were always in the Campus for late coffee and a tilt at the slots? They are spread thinly in the raucous eateries of a sadly commercial Main Street, and no longer does George tell them of the Greeks meeting Musso with the cold steel at Koritza. All those in favor of the rise of civilization signify by saying aye.

The Christmas spirit is not yet dead in the world. The merchants of the town, full of winter, set up Christmas trees on the sidewalks and hung them with lights (see above). A waitress in the College Inn got the idea quickly. She wrapped her Christmas presents, marked them "Do Not Open Until Dec. 25," and hung them on the tree outside the restaurant. All the passersby inspected them, and went on their way a little bit cheered.

Another nice story from the College Inn reveals that the roots of Culture go deep. Seems The Dartmouth ran a "Disc-riminating" column one day, reviewing among other things Beethoven's violin concerto in D major. A lad on the junior directorate of the paper walked into the Inn whist ling a refrain from the concerto, and the cook whirled around from his stove and said, "Geez that was a good column you ran this morning!"

Crown Prince Otto of Austria came to Hanover for a couple of days, and everyone was disappointed when he didn't arrive on a white horse. He did arrive with an aide de camp, however, so the cheering citizenry contented themselves with conjectures about the activities of Henry, Count Degenfeld, aide de camp in the aoth century to the heir of a vanished throne. "Does he set up Otto's tent?" they asked. "Does he carry a dispatch-case and sprinkle sand on Otto's messages (His Royal Highness sends his compliments to the President, and will the President honor His Royal Highness at tea today) after writing them with a quill pen? What is there left for an aide de camp, these days?"

It turned out that the prince was a charming and informed young man, no stuffed shirt at all, and there is talk of inv iting him back for a visiting lectureship. The uses of royalty-out-of-a-job are many, to be sure.

One of the sad and perverse items in a senior's life is that only in his senior year does he know how to study, and by then he finds he has less than a year of college so he wants to busy himself with enjoying the best of the gay life. He has, then if ever, a background of knowledge to build upon; he has perhaps for the first time a unified course of study that enables him to concentrate on a particular field of interest. For the first time in his college career the conditions are fine for education.

And then the wide wide world looms, and he knows the irony of the phrase in the drinking-song about "safe at last," and he suddenly wants to get everything he can from his friends, from football rallies, from basketball games, from skiing, from walking in the snow or out in the hills, from doing a good job in some extra-curricular activity or his fraternity or something else that absorbs him, from the lazy spring days ahead when the sun will ride high. It's a real conflict, and formal education usually passes him by. But who says he's not learning?

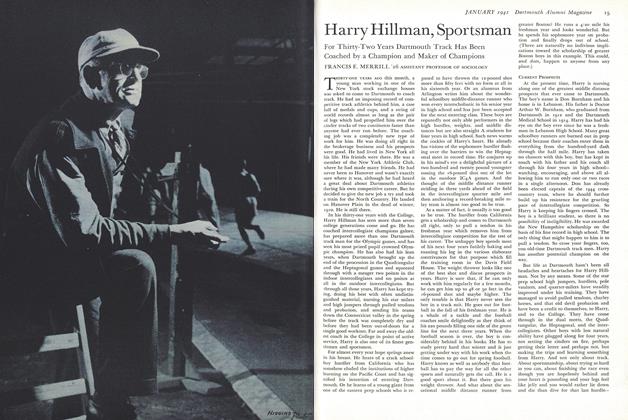

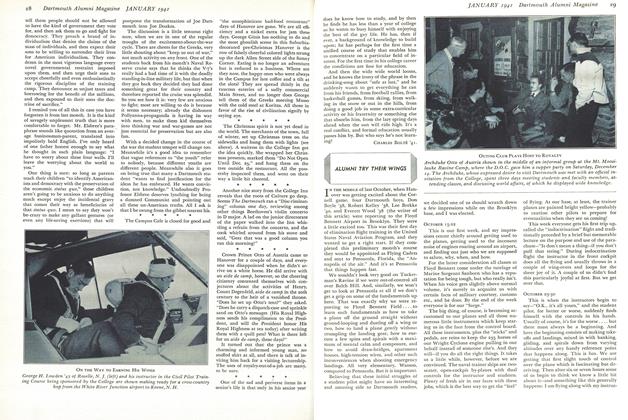

ON THE WAY TO EARNING HIS WINGS George H. Lowden '43 of Roselle, N. J. (left) and his instructor in the Civil Pilot Training Course being sponsored by the College are shown making ready for a cross-countryhop from the White River Junction airport to Keene, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHarry Hillman, Sportsman

January 1941 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Article

ArticleThat Men May Understand

January 1941 By HAROLD ORDWAY RUGG '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleALUMNI TRY THEIR WINGS

January 1941 By Everett Wood '38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

January 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR, ROGER C. WILDE -

Article

ArticlePreservation of Democracy

January 1941 By CLYDE C. HALL '26

Article

-

Article

ArticleGEORGE WILLARD NEWMAN '02

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleComparative Studies

MARCH 1963 -

Article

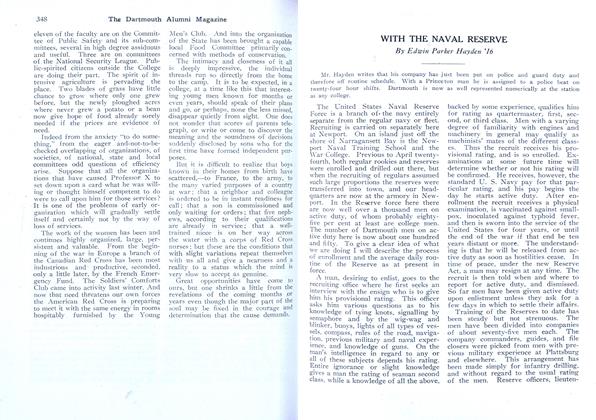

ArticleClassnotes

MARCH | APRIL 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Article

ArticleWITH THE NAVAL RESERVE

June 1917 By Edwin Parker Hayden '16 -

Article

ArticleNow Comes the Tug

June 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleMedical School

June 1940 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22.