IN THE MIDDLE of last October, when Hanover was getting excited about the Cornell game, four Dartmouth boys, Don Boyle '38, Robert Kelley '38, Lee Brekke '4O, and Everett Wood '38 (the writer of this article) were reporting to the Floyd Bennett Airport in Brooklyn. They were a little excited too. This was their first day of elimination flight training in the United States Naval Aviation Program, and they wanted to get a right start. If they completed this preliminary month's course they would be appointed as Flying Cadets and sent to Pensacola, Florida, the "Annapolis of the air." And it's at Pensacola that things happen fast.

We wouldn't look very good on Tuckerm an's Ravine if we were out-of-control all over Balch Hill. And, similarly, we won't get to look at Pensacola at all if we don't get a grip on some of the fundamentals up here. That was exactly why we were reporting to Floyd Bennett Field.... to learn such fundamentals as how to take a plane off the ground straight without ground-looping and dusting off a wing or two, how to land a plane gently without crumpling the landing gear, how to exec ute a few spins and spirals with a maximum of mental calm and composure, and how to avoid draw-bridges, apartment houses, high-tension wires, and other such inconveniences when shooting emergency landings. All very elementary, Watson, compared to Pensacola. But it is important.

Believing that these initial struggles of a student pilot might have an interesting and amusing side to Dartmouth readers, we decided one of us should scratch down a few impressions while on the Brooklyn base, and I was elected.

OCTOBER 15-22

This is our first week, and my impressions center chiefly around getting used to the planes, getting used to the incessant noise of engines roaring around an airport, and finding out just who we are supposed to salute, why, when, and how.

For the latter consideration all classes at Floyd Bennett come under the tutelage of Marine Sargeant Sanborn who has a reputation for being tough, but who really isn't. When his voice gets slightly above normal volume, it's merely to acquaint us with certain facts of military courtesy, customs etc., and he does. By the end of the week everyone is for our "Sarge."

The big thing, of course, is becoming accustomed to our planes and all those num erous little instruments which keep staring us in the face from the control board. All these instruments, plus the "sticks" and pedals, are reins to keep the 235 horses of our Wright Cyclone engine pulling in our behalf instead of someone else's. And they will—if you do all the right things. It takes us a little while, however, before we are convinced. The naval trainer ships are twoseater, open-cockpit by-planes with dual controls for the instructor and students. Plenty of fresh air in our faces with these jobs, which is the best way to get the "feel" of flying. At our base, at least, the trainer planes are painted bright yellow—probably to caution other pilots to prepare for eventualities when they see us coming!

This week everyone gets his first trip up, called the "indoctrination" flight and traditionally preceded by a brief but memorable lecture on the purpose and use of the parachute—"lt don't mean a thing—if you don't pull that string." During indoctrination flight the instructor in the front cockpit does all the flying and usually throws in a couple of wing-overs and loops for the sheer joy of it. A couple of us didn't find this particularly joyful at first. But we get over that.

OCTOBER 23-30

This is when the instructors begin to say—"O.K., it's all yours," and the student pilot, for better or worse, suddenly finds himself with the controls in his hands. Usually of course, it's for the worse .... but there must always be a beginning. And here the beginning consists of making takeoffs and landings, mixed in with banking, gliding, and spirals down from varying altitudes over any handy reference point that happens along. This is fun. We are getting that first slight touch of control over the plane which is fascinating but deceiving. Then after six or seven hours some of us begin to think we know a little bit about it—and something like this generally happens: I am flying along with my instructor who has told me to fly a 6g degree course at 800 feet of altitude. And when an instructor tells you to fly at 800 feet.... he means 800 feet. 825 feet will not do. Anyway .... I am flying along taking an occasional squint at the scenery when I hear my instructor speaking through the tubes, "Say, Wood, you went to Dartmouth didn't you?" (Yes) "Pretty fine school up there, isn't it?" (Yes, Sir) "By the way, Wood, do they teach you to read up there?" (Yes) "Then FOR * * * * SAKE-WHY DON'T YOU LOOK AT YOUR ALTIMETER?" But this is all part of the game. In flying the reactions have to be quick and the nerves in control. A student who falls apart under a slight burst of verbal criticism—will hardly be the picture of composure with a couple of Messerschmitts on his tail.

And so it goes. And the students (there are 24 of us) are beginning to talk about those "check" flights and "solo hops" which come at the end of our course—and which spell success or failure for our efforts.

NOVEMBER 1-7

My impressions of the third week could be summed up in the phrase—one long "cut-gun." "Cutting-the-gun" is simply your instructor turning the throttle off at the damndest places—the student's cue to push the stick forward (to maintain that all important air speed) and start shooting for an emergency landing.... not always so simple. My emergency landings had, if nothing else, always the virtue of surprise. Surprise to the instructor that anyone could be so bad. Surprise to numerous Brooklyn backlot land-owners when they saw a plane heading for their vegetable garden. Surprise to everyone when I finally began to do the right thing occasionally. These emergency landings do not, of course, always result in actually landing the plane. Sometimes they do. Usually, as we're about to settle down in a nice swamp or on a startled construction crew—we give her the gun and away. "Cut-guns" are designed to keep students thinking. Practically anyone can fly a plane under perfect conditions. But what the Navy wants are fliers who can do the right thing in an emergency—and do it fast. Engine trouble over a muskrat swamp (which is what cutguns simulate) gives the student practice in handling a few of the thousand possible emergencies.

Another memory of this week, a singularly vivid, was watching a test pilot put a new Brewster experimental fighter plane through its paces .... loops, dives, Immelmanns, split B's, snap-rolls, slow-rolls—with a cruising speed of 360 and a 40-degree climb. For all of us who were still struggling with our 3 point landings this was a humbling experience, a brief vision into things to come. But it was a challenge if I ever saw one.

NOVEMBER 8-15

Before taking our "check" flights we all go up for a brief trial at spins from 7 or 8 thousand. So here we go. When the instructor hits the right altitude he brings the stick back (nose-up) until the controls get heavy and the plane is ready to stall. Then, quick as a flash, stick forward, kick one rudder-pedal—and "ski-heil." The plane points down, the wings spin around and around and around, and, frankly, until we've done this a couple of times, we haven't the least idea whether we're coming Or going. Then the instructor kicks the opposite rudder, stick forward, the plane stops spinning and we are nosing a straight dive. Stick back now, the plane levels off and once more "God's in His Heaven." My first spin reminded me of my first trip over the Headwall—only this time the bottom of the Ravine wouldn't stay put. The next time is a lot easier. We have learned how to relax now. Ease forward, no tightened muscles—that's the key to the thing.

Now we're ready for our "check" flights —but instead it rains and blows. For four days it rains and blows. No planes up. This waiting is tough on the nerves—but good training. Also, it gives us a chance to practice up on receiving the International Radio Code. Before we leave most of the lads are taking 10 words a minute—which will do for a start.

At last good weather and my first "check" flight. On my second landing I miss a 10 degree wind-shift. That won't look at all well on the books. However, I pass. My second check is a bit tougher; a couple of cutguns, a little air work, a spiral down over the field from 1500 and we land. Then my instructor getting out of the plane. This time when he says "O.K. it's all yours"he really means it. So I get ready for my first solo. A very meek little hop, mind you, but all my own. Fortunately, those wonderful deities that watch over downhill racers and neophyte pilots (most of the time) are with me, and I take off, gain alti- tude, take a little ride and land. All with a minimum of confusion so I feel pretty pleased. There is a saying around Floyd Bennett to the effect that a successful solo flight is one when the student takes the plane up and down—and is able to walk away from the plane under his own power. So it appears that I pass. Just as I'm walk- ing into the gear room—splash! I get a pail of water down my neck. This is the tradi- tional manner of congratulating student pilots after their first 5010.... so I don't mind. In fact, that particular pail of water felt very, very good indeed.

The rest of the lads are "checking" now. So out comes a lot more water. Unfortunately, three boys have tough luck and don't get to solo. Everyone wishes the pails could have gone all around.

That night a big party is in order. Everybody sings, everybody wishes everybody else good luck. Everybody sees that the Sargeant gets all the rum he can handle. Next stop—Pensacola, Florida—where things happen fast. Maybe they'll happen too fast for us down there. Maybe they won't. In any case, we're sure of one thing. We're sold on the United States Navy as the finest military organization in this country. We hope we can sell ourselves to them. In the meanwhile—Pensacola, here's looking at you!

OUTING CLUB PLAYS HOST TO ROYALTY Archduke Otto of Austria shown in the middle of an informal group at the Mt. Moosilauke Ravine Camp, where the D.O.C. gave him a supper party on Saturday, December14. The Archduke, whose expressed desire to visit Dartmouth was met with an official invitation from the College, spent three days meeting students and faculty members, attending classes, and discussing world affairs, of which he displayed wide knowledge.

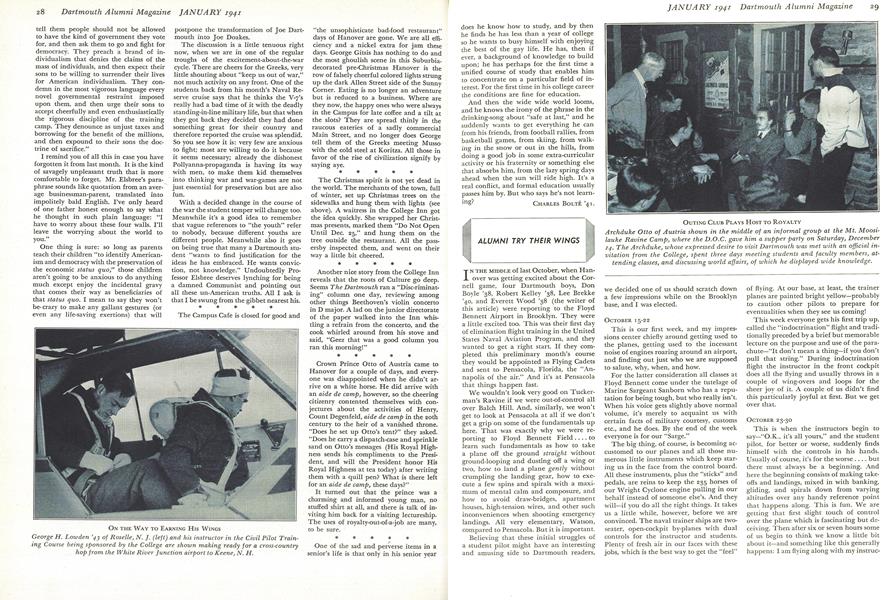

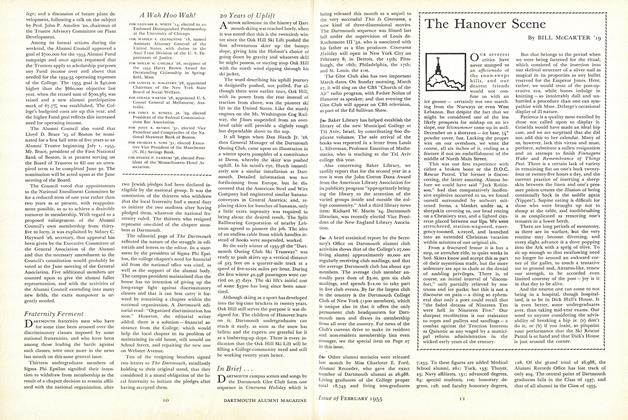

FOUR YOUNG ALUMNI TRAIN AS NAVAL AVIATORS Left to right: Bob Kelly '38, Lee Brekke '40, Don Boyle '38, Everett Wood '38.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

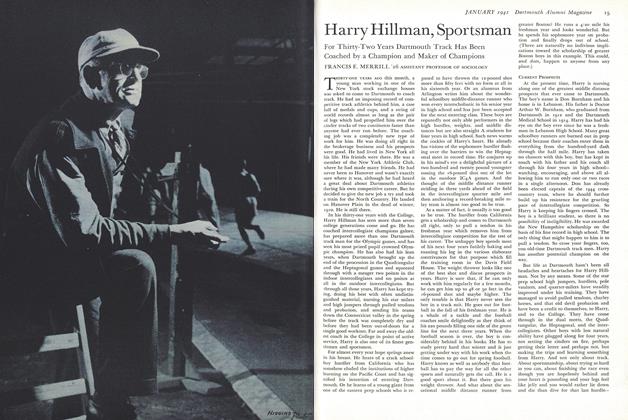

ArticleHarry Hillman, Sportsman

January 1941 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Article

ArticleThat Men May Understand

January 1941 By HAROLD ORDWAY RUGG '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1941 By Charles Bolté '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

January 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR, ROGER C. WILDE -

Article

ArticlePreservation of Democracy

January 1941 By CLYDE C. HALL '26

Everett Wood '38

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Books

BooksDistant Drum

December 1980 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDiseased With Poetry

MARCH 1995 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Everett Wood '38

Article

-

Article

ArticleIn Brief . . .

February 1955 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleTRACK

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Council

OCT. 1977 -

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Article

ArticleA Mac Arthur Award for Gary Tomlinson '73

NOVEMBER 1988 By JENNIFER AVELLINO '89