The Full Story of William E. Chandler, First ProgressiveRepublican, is Now Told by Professor Richardson

By Leon Burr Richardson 'oo. Dodd, Mead& Company, New York, 1940. p. 758. $5.00.

THIS BOOK, the latest volume in the series of American Political Leaders edited by Allan Nevins, is the work of the eminent Professor of History at Dartmouth College, a man steeped in the traditions of New Hampshire. As the author takes pains to indicate, it is "a story of politics,"—not always too savory,—in one of the most politically minded of the New England states between the Civil War and the World War, when power in the republic rested for the most part in the hands of the Republicans; and William E. Chandler was one of the most typical of the machine politicans and wavers of the "bloody shirt" in that by no means unblemished period. The Legislature of New Hampshire, with its unwieldy lower branch of more than four hundred members, is the largest in the Union; and the proportion of citizens actively engaged in political manipulation in small towns and larger cities was unusually large during the second half of the nineteenth century. Chandler was born within sight of the State House at Concord,-actually in a residence which once stood wherthe New Hampshire Historical Society is now located,—and his legal home was always near the center of state government. As a child, he attended meetings of the Legislature and characteristically criticised the debates for "irrelevancy relevancy and lack of sense." In later years he was to make similar comments on the floor of the Senate Chamber in Washington.

After brief intervals in country academies, Chandler studied in a Concord law office, went to Harvard Law School, and was admitted to the bar in 1855, before he was twenty years old. Indeed he assisted at the birth of the new Republican Party before he was himself old enough to vote for Fremont, and he was a sound, though not always orthodox, partisan throughout his career.

At twenty-seven, Chandler was Speaker of the New Hampshire House,—the youngest man ever to hold that position; and by 1864 he had risen to the Chairman of the Republican State Committee and was known as an ambitious lawyer with a fondness for extraprofessional political adventure. Then, to enlarge his private income, he moved to Washington, where he quickly became a powerful, even a notorious, lobbyist and eventually rather better than well-to-do. Professor Richardson defends Chandler against the imputation of corruption. What he did was to employ his wide acquaintance and experience for the benefit of his clients, who paid him well. Early in 1865, President Lincoln, aware of Chandler's services to the Republican Party, named him as Naval Solicitor and Judge Advocate General, and later, after the President's assassination, he became Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, in which post he remained for more than two years. By this date, Chandler's reputation as a sagacious, practical, and useful party manager had spread, and in 1868 he was the logical choice as Secretary of the National Republican Committee. In an era when money was expended freely in political campaigns, Chandler was certainly not unacquainted with the various picturesque forms of election chicanery then practised. He had a conspicuous, perhaps a decisive, share in settling the disputed presidential contest of 1876, and always regarded the defeat of Tilden as his greatest service to the nation. The story of his activities is too long to be even summarized here, but Professor Richardson, in his impartial story of that controversy, has made a noteworthy contribution to the material of history. From that moment Chandler was regarded by the Democrats as the man who "stole the election for Hayes," and the brand will never be entirely eradicated.

When Chandler's loyalty was rewarded by an appointment from President Arthur in 1882 as Secretary of the Navy, the hostile Nation described him as "a shrewd and not over-nice political manager;" but Mrs. Henry Adams called him later "the ablest man in the cabinet." Many of his acts in the Navy Department were scathingly denounced by his opponents, and there is little doubt that, in most of his appointments, he promoted the supremacy of the Republican Party. But he did accomplish some good and tried zealously to build a better fleet. Professor Richardson, who, to his credit, is no indiscriminate eulogist, merely states the facts and adds, "The reader may form his own judgment upon them."

In June, 1887, Chandler was chosen by the Legislature for the senatorial vacancy left by the death of Austin F. Pike. In Washington he was uncongenial to many of his colleagues because of his unswerving partisanship, his persistent aggressiveness in disputes, and his temperamental fondness for ridicule and sarcasm as oratorical weapons. In debate he was no gentle soul, and his rugged independence impaired several of his cherished friendships. In his prime he was a familiar Washington personage, short and slender, with a full beard like so many of the post Civil War statesmen, rather delicate in health and even slightly hypochondriacal, but full of nervous energy, a vigorous bicycle rider even after automobiles had for most persons become indispensable. The great achievement of Chandler's later life was his battle against the domination of the railroad interests in New Hampshire,—a battle which has earned for him the title of "the first Progressive." Winston Churchill's Coniston, with its delineation of the notorious Jethro Bass,—the "boss" of the state, modeled on an actua' person,—had grimly satirized the situation as seen by a reformer; and Chandler himself, once a railroad lobbyist, now fought the dictatorship with a dispassionate fury. Indeed it was the opposition of the railroads which, in January, 1901, blocked his hopes of re-election to the United States Senate; but although he suffered personally, his program met ultimately with victory. Even when Churchill failed of the gubernatorial nomination in 1908, the movement was not abandoned; and in 1910, after thirty years of protest, Chandler had the satisfaction of seeing Robert P. Bass elected Governor, with the consequent passage of numerous measures curtailing the sinister influence of outside corporations. Following his retirement from the Senate, Chandler was still the valiant warrior and expressed his views on every important public question. He died on November 30, 1917, a little short of eighty-two years of age.

It is a long and kaleidoscopic story of more than seven hundred pages which Professor Richardson has to tell, but he has related it throughout with meticulous scholarship, careful research, and judicious weighing of the available evidence. Like every first-class biographer, he has started without a thesis and has gradually, with successive strokes of the brush, perfected his portrait. From this book we get a picture of a somewhat inconsistent and unpredictable figure, a conservative gradually moving towards liberalism, a stormy petrel of politics, tolerant of devious methods but himself untainted by corruption, a typical product of an age which will probably never come again. Professor Richardson has covered his subject so comprehensively that the job will never have to be done again. Here, in these pages, is William E. Chandler, for good or for ill. In some respects he seems antediluvian, and in an age when radical changes have become commonplace, his biography raphy may not arouse enthusiasm. Nevertheless I have found this book both interesting and illuminating, and I commend it to all Dartmouth men who are concerned with history and government, or indeed with human nature, of which William E. Chandler certainly possessed his full share.

LEON BURR RICHARDSON

HEADMASTER, PHILLIPS ANDOVER ACADEMY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleClassicist Not Without Honor

February 1941 By Donald Bartlett '24 -

Article

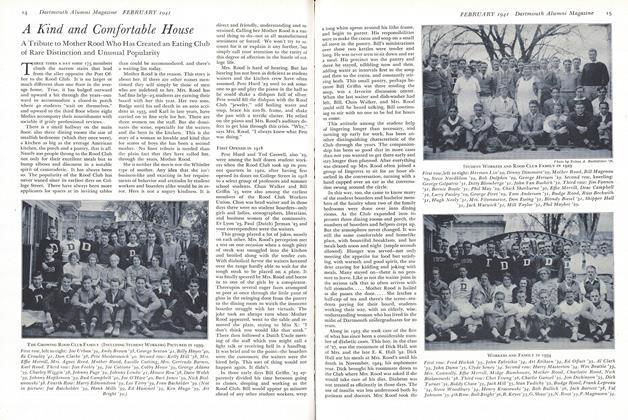

ArticleA Kind and Comfortable House

February 1941 By S. C. H. -

Article

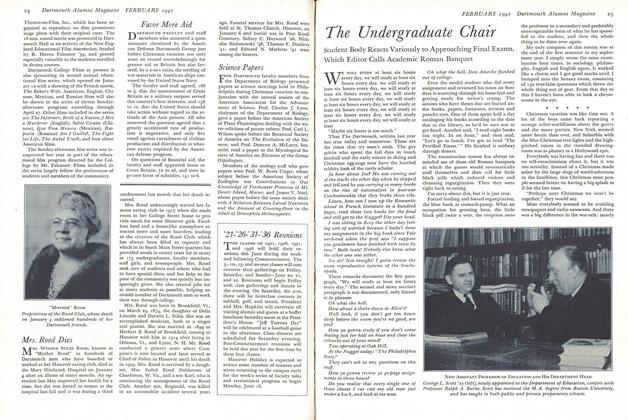

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1941 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924*

February 1941 By ALFRED A. ADAMS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939*

February 1941 By ROBERT W. GIBSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

February 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.

Books

-

Books

BooksPROFESSORS' BOOK SHELF

Mar/Apr 2008 -

Books

BooksPHYSICAL CHEMISTRY FOR PREMEDICAL STUDENTS

October 1946 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10. -

Books

BooksTHE INTERNATIONAL COURT

October 1932 By D. L. S. -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

JUNE 1973 By J.H. -

Books

BooksEDUCATION FOR PLANNERS

January 1943 By Walter Curt Behrendt -

Books

BooksA Barrier of Maple Leaves

February 1976 By WALTER H. MALLORY