By Harold L. Wilensky andCharles N. Lebeaux '35. New York: RussellSage Foundation, 1958. 401 pp. $5.00.

This book is a happy marriage of the "theoretical" and the "practical" in social science research. The theoretical problem is to study social change in the light of industrialization. The practical problem is to relate these changes to the institutions dealing with social welfare. Technology is seen as the prime mover of social change in an industrial society; changes in industry and business follow those in technology; social institutions and class relationships follow in turn; social problems arise from these dislocations in the structure of society; and new facilities of social welfare are needed to deal with the resultant maladjustments. In this sense, the book presents a classic problem in social change, with technology at one end of the scale and social welfare at the other.

The present volume grew out of a request by the United States Committee of the International Conference of Social Work to the Russell Sage Foundation to prepare a statement on the relationships between industrialization and social work. The Foundation, in turn, called upon the two authors who are, respectively, an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Michigan and an Associate Professor of Social Work at Wayne State University. Their combined skills have produced a report that merges the theoretical interest of the sociologist in the process of social change with the practical interest of the social worker in the problems arising therefrom.

In the body of the book, the authors devote themselves to such questions as the following: (1) Why do the problems of old-age insecurity, unemployment, and poverty become more rather than less pressing in an age of "plenty?" (2) Why do private agencies of social welfare continue to play a basic role in the face of the continued expansion of the welfare state? (3) Why does juvenile delinquency remain a pressing problem in view of full employment, extensive welfare service, and large-scale public housing? (4) Why does family disorganization in the form of desertion and divorce persist despite increasing family income, leisure-time, and "togetherness"? (5) What is the role of the social worker in mitigating or eliminating these and other problems of an industrial society? These are problems that concern the average citizen as well as the professional worker. In a dynamic society, such problems can never be fully "solved." This book focuses the ordered knowledge of the social scientist and the practical experience of the welfare administrator upon the perennial problems of an industrial society.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Examined Life

July 1958 By THE REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH -

Feature

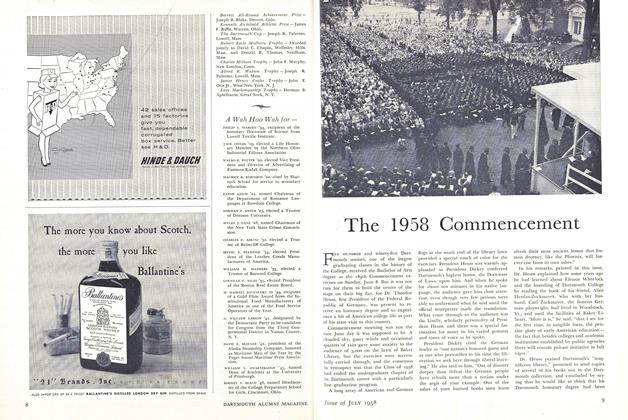

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

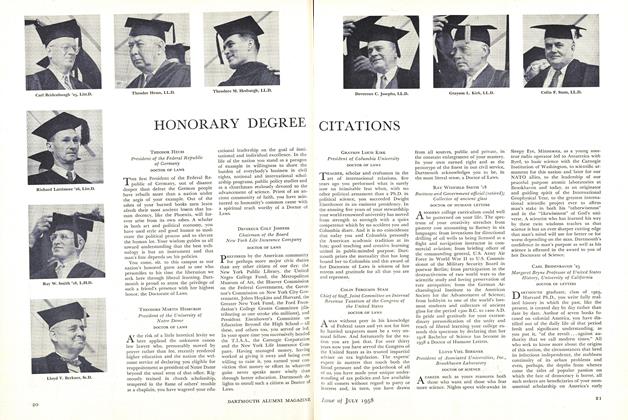

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

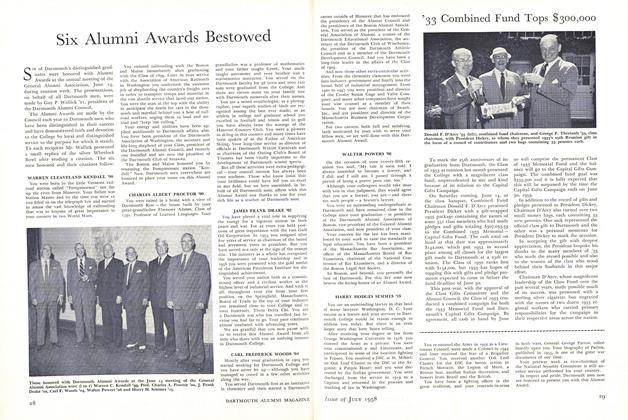

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

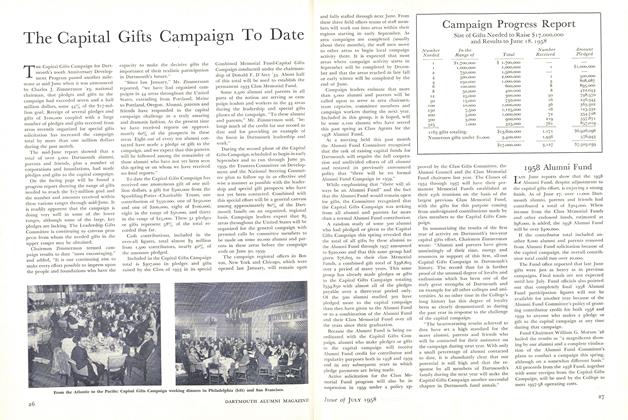

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58

FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26

-

Sports

SportsMISCELLANY

January 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

March 1947 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH 0, HOLY CROSS 0

November 1947 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH 27, HARVARD 7

December 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

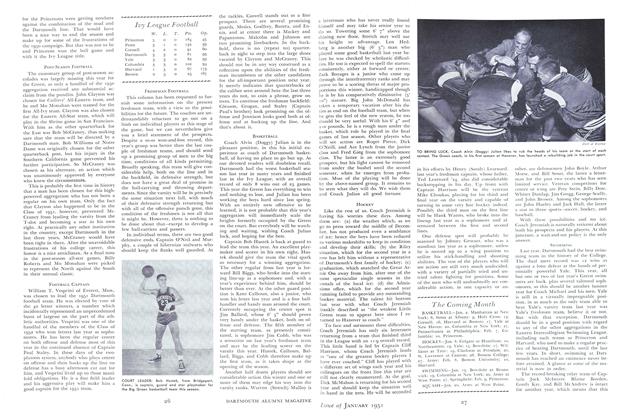

ArticleFOOTBALL CAPTAIN

January 1951 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

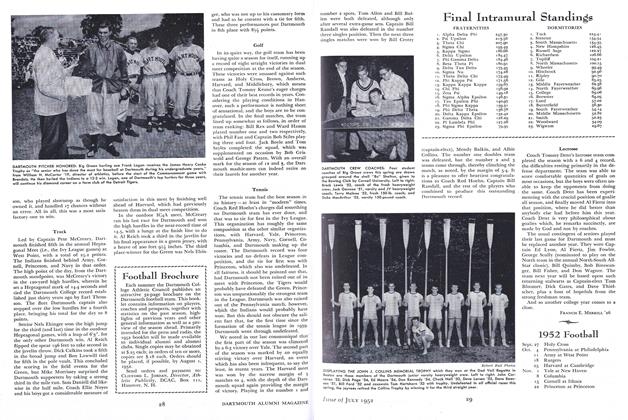

SportsLacrosse

July 1952 By Francis E. Merrill '26

Books

-

Books

BooksLEPROSY in EUROPE

June 1929 -

Books

BooksCanoe Club History

MAY 1967 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN DEMOCRACY IN THEORY AND PRACTICE. THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT

October 1951 By Landon G. Rockwell '35 -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksTHE QUARRY.

JUNE 1964 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksMANAGEMENT POLICIES FOR COMMERCIAL BANKS

November 1973 By STEVEN W. DOBSON