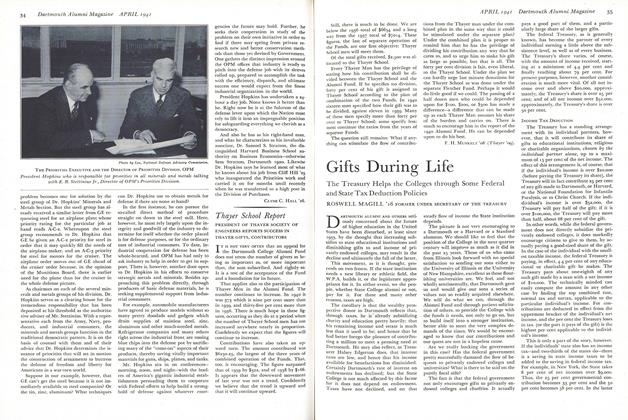

For a Quarter-Century Dartmouth College Has Grown Immeasurably in Stature, Spirit, and Prestige Under the Wise and Far-Sighted Guidance of a Great College President

WITH THE PRESENT YEAR Ernest Martin Hopkins concludes his twenty-fifth year as President of Dartmouth College. But two of his ten predecessors have served the institution so long —John Wheelock, whose administration ended in the great dispute of the Dartmouth College Case, and Nathan Lord, whose activities terminated in the contentions arising from the Civil War. A quartercentury of devoted, single-minded and, above all, effective service; a quarter-century during which he has so woven himself into the very warp and woof of the institution that it seems impossible to imagine the College without him. Truly the ALUMNI MAGAZINE cannot let the occasion pass without recapitulation of the fruitful years embraced by his presidency.

Nevertheless, in the hands of the present writer the problem offers certain difficulties. It is not easy to keep from the article the spirit of jocularity and persiflage which has marked the contact of the President with his old friends, on the faculty and elsewhere, during all these years. When he was informed that this article was to be written, his only request was that he should not be made to appear as a "solemn ass." The obvious retort was that every attempt would be made to keep the idea of solemnity out of the characterization, but, beyond that point, it was unreasonable to expect that further concessions could be made. That type of retort is hardly imaginable as being made by a member of the faculty to the dignified Presidents of the College who were President Hopkins' predecessors; or, if it were, the intent would have been serious and the words would have been regarded as "fighting words."

The writer well remembers the dignified and formidable Samuel Colcord Bartlett, then in retirement in the last two years of his life, his immaculate topper and frock coat imparting dignity to his erect form even when that form impelled itself through the community on a vehicle so incongruous as a bicycle. Persiflage was not thought of in contacts with so austere a personality, although, if tradition is to be trusted, biting and effective sarcasm was not absent from the daily conversation of that dignitary, without it being a matter of record that he was complaisant to retort in kind. Such is not the picture of President Hopkins. It is doubtful if he owns a "tall hat"; if he does, he certainly never has had the courage to exhibit it in Hanover. Nor does he possess a particle of the spirit either of the "tall hat" or the "stuffed shirt"—with him give and take are limited only by the fact that his capacity of giving is generally so superior to the similar capacity of those with whom he is in contact that the victory in such contests is likely to rest with him. But in a dignified article of this character it is to be remembered that he is President of the College and that a degree of decorum not required in ordinary conversation certainly is called for. So the reader may consider the "wisecrack" given above to be withdrawn as never said and that in the remainder of this production a proper air of dignity will prevail—broken as little as may be by inappropriate ribaldry resulting from the natural impudence of the writer.

EARLY SETTLERS IN NEW ENGLAND

Ernest Martin Hopkins is descended from Solomon Hopkins, of Scottish origin, who came from the north of Ireland to Newcastle, Maine, about 1735. Solomon and the generations of Hopkins who followed were plain people, farmers for the most part, men of substance and influence in their communities, but without special distinction outside. The family habitat continued to be Maine, first in Newcastle, afterwards in Jefferson. The grandfather of Ernest M., however, showed a greater spirit of restlessness, running away to sea as a lad of twelve and serving for many years as master of a coasting vessel. On the maternal side the line goes back to George Martin, who came to America about 1639 and settled in Salisbury, Mass., afterwards moving to Amesbury. With Susanna North, wife of George, a more stirring note (although Susanna probably would not have applied that term (o the incident) enters the story. She was executed as a witch on July 19, i6gs, one of the charges against her being that she proceeded from Amesbury to Newbury on foot in a "dirty season" without getting her clothes wet. Years later Whittier referred to the tragedy in the poem, The Witch's Daughter. Another maternal ancestor, Thomas Emerson, was also the ancestor of Ralph Waldo Emerson. At the end of the eighteenth century the Martin family removed to Baltimore, Vermont, and from that time resided in that state. Like the Hopkins, the Martins were ordinary people, for the most part well-to-do farmers, esteemed and useful in the communities in which they lived. In both lines a number of representatives of the families were soldiers in the Revolutionary War.

Adoniram Judson Hopkins (the name recalls the Baptist affiliations of the family), born in 1847, spent his earlier years as a worker in the Boston markets. His father was not sympathetic with his ambitions and would have nothing to do with the idea of higher education. Becoming his own master at the age of 21, the young man (as so often happened in those times) determining to advance by his own efforts, prepared himself for college and was graduated from Harvard in 1874, at the age of 27. He then attended the Newton Theological Seminary. During this latter course he preached for a time at Perkinsville, Vermont, and there met Mary Martin. The two were married in 1877.

The young minister took up his life work in a small parish and so continued, in communities of moderate size, during the whole of his preaching career. His family affiliations were with the Baptist Church and he found in that organization, with its freedom from authority, external or internal, welcome opportunity for development along lines of his own tastes and preferences. Never solicitous for the attractions offered by large fields of endeavor, in the country town, with its close feeling of intimacy, he found the opportunity which most appealed to him for the work which he most wished to do. High financial rewards were not a consideration, never did his salary exceed f 1200, but, so long as the simple needs of his family were met, he was content. His interest was in Christianity in the elemental form in which it was set forth by its Founder; he had no taste for the theological obscurities and subtleties which, in the minds of the majority of his brother clergymen of that time, had replaced the more genuine basis of religion. As a result, he did not escape the criticisms and protests of his doctrinally minded colleagues, nor, in all cases, of parishioners who posed as amateur theologians. Nor did his independence in matters political and social always appeal to the more extreme partisans among the members of his congregations. But, a man who coupled high intelligence with a gentle and winning personality, his influence upon all around him was profound.

In one of these small parishes, at Dunbarton, N. H., Ernest Martin Hopkins was born, the eldest of three sons, on November 6, 1877. Successively the family resided in Hopkinton and Franklin, N. H., then ensued a hiatus of three years when the Reverend Adoniram felt compelled to give up his ministerial work to care for his father in his last years in Boston, and then a parish at North Uxbridge, Mass., where the formative years of the boy were spent. Family fortunes were never highly prosperous, at times even the meager salary was far in arrears, so that it was necessary for each of the boys, as soon as he was able to do so, to contribute to his own support. For twelve years, during the vacation periods, Ernest was employed in the heavy work of the granite quarries at Uxbridge, beginning with the stipend of seventy cents a day, but rising eventually to the position of derrickman when those devices had as their motive power human muscle rather than the energy of steam or gasoline.

Years later, when acting as arbitrator in the labor difficulties of the granite industry of Barre, he was taunted by the granite workers that he had no real acquaintance with the troubles and hardships of those workers themselves. This contention he silenced by producing the union card which he carried as a worker, years before, at Uxbridge as convincing evidence to the contrary, although it is to be admitted that he refrained from calling attention to the scar still visible on his scalp, coining from contact with a stone hurled at him by a union workman in those early days as an effective method of fostering the desire for union membership. But all was not work the companionship of the kindly and sympathetic father, who made the boy a confidant in his intellectual speculations, was of the highest value in the development of the growing lad.

Eventually it was found possible for him to attend Worcester Academy; under the leadership of Dr. Abercrombie, one of the better of New England's preparatory schools. Financially he was largely on his own, but he was assisted in paying his way by the income from the post of mail carrier, which involved each day two trips of four miles each, upon foot, to bring the mail of the school from the Worcester post office. His intellectual tastes were stimulated by the effective teaching of Dr. Abercrombie, while he made friendships of influence upon him throughout life with such men as Charles Proctor (for whom he secured work during the summer as fellow derrickman at Uxbridge), Lemuel Hodgkins and many others.

His selection of a college seemed foreordained. Worcester was inspired with the Harvard atmosphere, the principal making no secrecy of his belief that, while those of inferior mental equipment might secure advantages commensurate with their limited intellects at other colleges, for the boy who really had any brains the only institution which was worthy of the slightest consideration was Harvard. Moreover the father was a Harvard man and regarded it as a matter of course that his son should attend the institution which was his own alma mater. Then, too, so far as Dartmouth was concerned, there was a special objection which, at the present time, strikes us with amazement. By the more straightlaced of the clerical element it was considered to be a most dangerous experiment to expose ingenuous and easily influenced youth to the subversive influence of so heretical a person as Dr. Tucker, who, it was well known, had wandered from the orthodox path to such an extent that he even doubted the eternal damnation of those heathen who had never been exposed to Christian teachings, nor was he confident that such a fate would be encountered by children who had died at a period too early to understand such doctrines.

In the case of the North Uxbridge boy his selection of a college was even made the subject of a special conference by some of his father's clerical associates, in which prayer was offered that, by divine interposition, the son should be turned away from so dangerous a course as entrance to Dartmouth would be. But the boy had a mind of his own. He was determined to enter the college of his choice and even the prayers of the godly could not prevail against that obsession. The father, although moved by no such illiberalmotives, naturally was disappointed, but gave waywith, however, one stipulation: that his son should not take advantage of the certificate system, evidently regarded by the Reverend Adoniram with suspicion as a sort of tricky entrance by the back door, but, in open, straightforward fashion, should pass the Harvard examinations themselves, the only valid test of scholastic competence. Such a process required time, moreover the financial problem would be made easier by a period of teaching. So for a year the young man carried on the task of instruction in the grammar school at North Uxbridge, developing thereby his sense of tact in the handling of youth, and also the technique best adapted to throwing obstreperous lads out of the door when tact proved of no avail. But in September, 1897, he presented himself at Hanover with a full record of examinations passed entitling him to admission to Harvard, only to be told by Dr. Tucker that he had already been accepted the previous April on papers from Worcester.

So the class of 1901 received an upstanding recruit, perhaps somewhat awkward and ungainly in person, possibly a bit rustic in manner, but who quickly demonstrated the worth that was in him. His most intimate friends were in the class above his own, but he soon won a place among his immediate classmates. He had his own way to make and, at times, that way seemed entirely closed. Thus in the latter part of his freshman year he was actually obliged to leave college for the want of so small a sum as $25 and, in his own mind, the prospects of the continuance of educational opportunity seemed entirely dark. It was at this time that he was encouraged to further efforts by a special visit to his Uxbridge home by his friend, Charles Proctor, and by the helpful assistance of Charles' mother at whose house he roomed in his sophomore and junior years.

As time went on, the way became clearer. Still, at no time either in his school or college course was he free from the requirement of making his own way. On that account he never had time for participation in athletics, despite his intense interest in sports, so to this day he has no idea whether he would have attained proficiency in any branch of athletic endeavor. For the same reason he made no outstanding scholastic record, although always maintaining a creditable rank and at one time winning the Lockwood prize in English composition. He remembers with special favor the qualities of certain of his teachers—the accurate, exacting scholarship of Charles D. Adams, the equally exacting but a bit more human traits of John K. Lord, the inspiring qualities of Charles F. Richardson, the broad scientific vision of William Patten, the clear, concise and logical exposition of Frank H. Dixon. In his junior year he was editor-in-chief of the Aegis and he was also on the editorial board of The DartmouthLiterary Monthly. His active part in athletic management began with his membership for two years as undergraduate member-at-large of the Athletic Council. In his senior year he attained the distinction of becoming editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth. In this position his productions were, perhaps, not outstanding, nor without traces of immaturity, but his expressions were marked both by a sense of balance and by interest in educational progress not always characteristic of undergraduate editors. He was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon, of Casque and Gauntlet, and of Palaeopitus.

Upon graduation he became secretary to President Tucker. With the growth of the College the duties of the presidency had become too exacting to be carried without assistance and for the first time aid of this kind became essential to the head of the institution. Dr. Tucker had been attracted by the tone of the editorials in TheDartmouth in the preceding year and, largely on this basis, selected their writer for the position. Then, perhaps for the first time, the education of Ernest Hopkins in the broader sense began. Years later, at the time of President Tucker's death, his former assistant pronounced him to be the greatest man he had ever known, and this at a time when he had come into more or less intimate contact with most of the leaders of American life. The impact of this vivid personality upon one who was still at a somewhat immature stage of development at times had its amusing aspects. Thus, on one occasion, when they were taking a long train journey together, the President moved into an adjoining compartment with the observation that he wanted quiet in order to think. The idea that anyone consciously and with malice aforethought could set himself to the deliberate process of thinking was a new one to the young man and, upon further consideration, he arrived at the conclusion that, for his own part, not only had he never set himself deliberately to think, but probably he had never done any real thinking in any circumstances. It was by unconscious methods like these that Dr. Tucker contributed so much to his secretary's education.

While the then head of the College was always considerate and patient, he defi- nitely expected efficiency and energy on the part of those subordinate to him, together with the development of independent decision and judgment, and, most of all, the willingness to assume responsibility when occasion should arise. He soon found that his new subordinate either possessed or was capable of developing these qualities to a most satisfactory degree. At the very beginning, the complicated arrangements necessary for the celebration of the Webster Centennial were largely in Hopkins' hands and the smoothness with which the festivities were carried out was the occasion of general comment. The ceremonies of Commencement Day, practically in the form in which they now exist—a model to other institutions—were also planned by the new secretary. When Dartmouth Hall burned, while the first incentive to measures of reconstruction was supplied by the enthusiasm of the members of the Boston alumni, that enthusiasm waned sadly in the detailed and laborious work of the actual campaign. That task had to be assumed by the President's office, with the Secretary in charge, and the succ'ess of the enterprise was largely due to his energy. For two years he was also graduate manager of athletics, the second person to hold that post. Even today the recollection of members of the Athletic Council of those times is keen concerning the breath-taking series of expenditures proposed by the manager, and the astonished perturbation with which the conservative members of the group looked upon these seeming extravagances. But these conservatives eventually were compelled to admit that, although he spent money, in their words, like a drunken sailor, he always got the money to spend. It was, in fact, during this period that a beginning was made of arrangements with other colleges involving a financial return for Dartmouth which was commensurate with the importance of the College, and, as a result, athletic finances were placed on a much broader basis.

In 1905 he was advanced to the newly created position of Secretary of the College. The work connected with this office required all his time, so that no longer could he continue as graduate manager. Upon his departure from that position his effectiveness was recognized by the award to him of the athletic D. He was now known to be, not only an efficient executive in the management of detail, but one whose vision and foresight were to be of the highest advantage in forming the larger policies of the College. One of the great accomplishments of Dr. Tucker was to make the alumni body an active and fruitful part of the College organization. Nevertheless, at this time alumni participation in college affairs to a large extent was handicapped by an organization which lacked flexibility when necessity arose for quick response. It was through the Secretary's initiative that in 1905 the Association of Class Secretaries was formed, which soon proved itself a most helpful part of the College organization and which paved the way to even more serviceable development of alumni machinery in later years. The first fruit of this organization was the foundation of the DARTMOUTH BIMONTHLY, now the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, which ever since has been under the jurisdiction of the Association of Secretaries. Hopkins was the first editor of the publication, serving from 1905 to 1910.

In connection with this editorship he made his first venture into the region of educational controversy, with a questioning of the entire efficiency of the training for the Ph.D. degree as a preparation for teaching in the liberal college. This critical attitude in relation to one of the most venerated of the "sacred cows" of the academic world called forth, as might have been expected, heated rejoinders from the defenders of the system, in which the strictly objective attitude, which the training for the degree is supposed to inculcate, was not always clearly in evidence. In such disputes two methods are commonly adopted by defenders of the system: first, that no one who has not himself attained the degree has any right to express or even to hold an opinion concerning its validity; and, second, that an attack on the requirements for the degree as a method for training teachers is an attack on the whole principle of scholarship and an appeal for superficiality and lack of genuine learning. The controversy had no more definite educational outcome than the relief of the minds of those engaged in it, but it did bring upon the Secretary the disesteem of those faculty members most extreme in their devotion to technical scholarship and the maintenance of the status quo. The problem, however, remains an unsettled one to this day.

The administrative conditions in the College during the last two years of Dr. Tucker's service were such as to make the position of the Secretary one of much difficulty. While the Trustees were fumbling with the apparently hopeless problem of selecting a worthy successor, the President, his health badly impaired, could undertake to perform only a strictly limited amount of work. Decisions in many cases thus devolved upon the Secretary and his personal devotion to the President (as well as the confidential instructions of the Trustees) led him, with the object of sparing his chief as much as he could, to assume a large measure of responsibility in the management of College affairs. So at this time the greater number of matters of minor import and some of those of larger significance were decided by him. It was not a responsibility which he would voluntarily have assumed, nor is there any record that the oonclusions which he reached were not those which Dr. Tucker himself would have arrived at. Those closest to the President recognized the necessities of the occasion and approved the course of action taken. But there were others in the College organization, perhaps not entirely cognizant of the exigencies that existed, who resented the fact that so young a man, and one who had no official authority in such matters, loomed so large in the management of the institution. That difficulty, of course, was removed by the advent of Dr. Nichols in 1909. Secretary Hopkins was largely responsible for the management of the elaborate ceremonies of the inauguration and continued in office during the year. At the end of it he submitted his resignation. Highly cherished by him is the gold watch presented to him by the undergraduates upon his departure. His association with the student body had been constant in many ways, among others in the responsibility which was assigned to him of selecting speakers of distinction for the then popular series of lectures known as smoke talks.

The work in the industrial field which was to engage his attention for the next seven years was the problem of personnel. It had dawned upon the more far-sighted of business executives that, while careful attention had been paid to power, plant and machines, enormous wastes were being incurred by the crude methods with which the men and women who were to utilize these appliances were being treated. At this time the field of employee relations, as a problem of business, was untouched in any scientific way. Obviously it bristled with difficult, varied, and complex problems, requiring extensive and well-planned research and demanding also hard sense in the application of the results of that research to the practical workings of the industry as a whole. It was to the solution of such problems that Hopkins was henceforth to apply his activities, first with the Western Electric Company at Chicago, then, in succession, with organizing or developing the employment systems of the great Filene department store in Boston, of the Curtis Publishing Company, with its wide range of activities, and finally of the New England Telephone Company, with the assured prospect of soon being called to do more extensive work for the parent Bell Company as a whole.

He rapidly assumed a position of authority and leadership in this new but rapidly growing field, as instanced by numerous papers in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science and elsewhere. His productions were characterized by broad grasp of the problems involved, by appreciation of the necessity of continuous research and, most of all, by recognition of the fact that the solution of the problem, if it is to be of any value, must permeate all branches of the industry concerned, and avoidance of the error, still far too common in this type of organization, by which high principles and well-formulated policies concerning personnel evolved by authority from above, become so diluted and denatured, as they trickle down to the lower ranks, that they are regarded with derision by the minor bosses who have immediate relations with the workers, and with contempt by the workers themselves as arrant hypocrisy.

On February 2, 1911, Hopkins was married to Miss Celia Stone, who for eight years had served as private secretary to President Tucker. A daughter, Ann, now Mrs. John Rust Potter, resulted from this union, and, by the birth of John Rust Potter Jr., in December, 1940, the President and Mrs. Hopkins have recently been advanced to the distinction of grandparents.

Activity in the business world by no means lessened Hopkins' interest in the College. He was primarily responsible for the institution of the Dartmouth Alumni Council, first suggested by him to the meeting of the Secretaries in 1910, endorsed by that Association in the following year, its constitution drawn up in 1912, and soon after approved by mail ballot by the alumni as a whole. This organization has since proved itself to be indispensable in providing an alumni group, large enough to be representative but sufficiently small so that its deliberations can be effective. Serving as a medium of communication in either direction between the alumni and the active College, intrusted with definite and important responsibilities along varied lines, more than any other organization it has had to do with making the alumni an actively serviceable part of the College. Its originator was elected its first President.

In November, 1915, this group propounded to the Trustees three questions for discussion, two of them relating to finances and scholarships, but the third and important one asking for the establishment by the College administration of a definite educational intention for the institution, with the emphasis most decidedly on the word definite. This appeal apparently took the administration by surprise and at first its reply was somewhat vague, but at a joint meeting of a committee of the Council and one appointed by the Trustees, held later in the year, a frank discussion of the fundamentals of College purpose was carried on, and while no conclusive result at the time ensued, the attention of the Board was fixed very directly on Hopkins, chairman of its consulting committee (who was, in truth, the originator of the issue), as one inspired by constructive ideas on the general subject of education in the liberal college, with particular application to the future of Dartmouth.

On an especially dirty and sloppy Sunday morning early in the winter of 1915-1916 Hopkins was awakened by the telephone. General Streeter, a leading trustee, was on the line summoning him to a conference at a hospital in Boston, where the General was immured as a result of a slight operation. The recipient of the message, in private, uttered feeling objurgations at the dominating trustee who should thus summon him from leisurely and comfortable consideration of the sporting page and Little Orphan Annie* in such summary fashion, but, none the less, grudgingly complied. On reaching the hospital he was received with the abrupt statement, "President N ichols has resigned and you are to be the next President of Dartmouth College." In reply to the sputtered expostulations and objections of the victim, the General grimly said, in effect, "That is all right; you are supposed to make such statements, you are supposed to expostulate, you are supposed to raise objections, you can keep on doing it for any period in reason so long as you like, but, at the end, you are to be thenext President of Dartmouth College."

In truth at this time Ernest Hopkins had no desire whatever to be President. He was happily located, he was doing work which offered high opportunities for effective service, work which he liked and in which he was highly successful, with the most flattering prospects for the future. No one better than he knew the difficulties and exasperations of college administration. As a life calling, the position offered few attractions to him. Often has he expressed his astonishment that any person should consider the acceptance of such an office unless a strong emotional tie bound him to the institution involved. The existence of that tie between him and Dartmouth was entirely real and was the only consideration which led him not summarily to reject the proposal. And soon his resolution was shaken by a great variety of appeals from those whose advice he most cherished. In particular, Dr. Tucker made the strongest of pleas that, at whatever expense to his own comfort, he should embrace the opportunity to be of service to the institution. In response to his protest that he was too young for the office the former President dryly observed that that objection, at least, was sure to be removed in the lapse of time.* So, perforce, he was compelled seriously to consider the position.

But the way was not entirely clear. A board of trustees, if it is wise, will arrange to announce the successor of a president at the same time that his resignation is made public. While that choice will be criticised, the board cannot be subjected to the importunity of the friends of a multitude of other candidates. When it became known that Hopkins was under consideration, violent opposition, limited, it is true, in numbers, but not in severity, broke forth. One member of the faculty proclaimed that such an election was equivalent to the request for his own resignation, which would be promptly submitted (and was not, in. the final event). Others deplored the choice of a man assumedly so lacking in appreciation of real scholarship. Others were doubtful of possible over-emphasis of athletics. Personal animosities, coming from differences in the days of his service as Secretary, were not without their effect. Members of the alumni also had various objections. The departure from the practice of selecting ministers or educators for the position was deplored by the more conservative; in any case, if such a departure was to be made, it should not be in the direction of a youthful man of business. It was vehemently asserted that Hopkins was not "a big enough man" for the position. One minor alumni association committed itself against the choice. Various graduates suggested candidates of their own, some of them worthy of consideration, others ludicrous in their inadequacy. Certain individuals coyly let their friends know that they would accept the position, if the emergency requiring that action should arise.

In general, it may be said that a considerable and most enthusiastic group (including practically all the Trustees) favored the selection of Hopkins, that a smaller but very vociferous body definitely opposed that choice, while the great majority both of the alumni and of the faculty, although they cherished some doubt as to the wisdom of the selection, thought it offered sufficient promise of success to make it worth a trial. At the end, the person most concerned changed his attitude. Perhaps he felt excusable irritation at the character of some of the opposition; certainly he was opposed to the course which he was convinced the Board would take if he was not chosen (although his objection was directed against a principle and not against any individual). At the end he became an entirely receptive candidate. And so, after much discussion and delay, the outcome was that which General Streeter had predicted; after all the expostulations, after all the objections, Ernest Martin Hopkins was elected eleventh President of Dartmouth College on June 13. 1916, and at once accepted the office.

The work of the next two years was a striking example of the highest type of personal leadership. The somewhat divided state of the College organization has been described above. That state of division, ranging from open opposition to dubious uncertainty, was removed as if by magic. Upon close contact with the new executive the faculty found complete agreement with their scholastic aims for the institution, even if that scholarship were of the most technical kind. It became apparent that the sympathy shown by him for their ambition that the institution, from the point of view of scholarship, should be an institution of superior type was no less pronounced than that shown by the clerical gentlemen who had supplied leadership for the College for somany years. And in many cases it had more immediate results. Worth-while suggestionswere received with understanding and, what is more to the point, not with the response, so common with some administrations of the past, "It is an excellent idea; I wish that we had the money to doit," but with the more co-operative reply, "It is an excellent idea; let us see where we can get the money to do it." And often,, very often, the money could be and was. obtained. Relations with the undergraduates were no less satisfactory.

The new President devoted himself sedulously to visits to the alumni. In his formal speeches to them, while the element, of lightness had its proper place, in general he made no concessions to entertainment or amusement, but, in utterances that by some might be regarded as on the heavy side, he set forth in detail the internal! and external problems of the institution in their relation to the prevailing social order. Despite the fact that these utterances required the undivided attention and the intellectual participation of his hearers, never did he fail in holding that attention and in arousing real interest, not only concerning the progress and prosperity of the College, but upon the contributions of the institution, as they were and as in the future they might be, to the American way of life. Usually the formal meetings were followed by free and open discussion of all things under heaven in smaller groups (bull sessions they would be called, if they were conducted by undergraduates) extending, in smoke filled rooms, far into the morning hours, in which the personal impact of the President upon multitudes of alumni was far extended. Credit is hardly due to him for submitting to the physical and mental exhaustion of these informal discussions, for of all things they were the occasions which he enjoyed the most and he was usually the last to suggest that they break up.

The result of these alumni contacts was soon evident. By the impact of his personality he soon removed the doubts of the wavering; by it in equal measure he won over even his most exacting opponents so that they became his. strongest supporters. While differences of opinion as to details continued and always will continue to exist, while controversy was not eliminated, nor was it his desire that it should be, in a time remarkably short the Dartmouth constituency became unanimous in the sentiment that it was possessed of a great leader; one. moreover, not merely re- spected and admired, but held in personal affection by all its members. Such consolidation of feeling was a remarkable example of the efficient employment of tact and skill in the management of men: but not a form of tact which had any relation to insincerity or hypocrisy, not a mode of management depending upon methods consciously pursued, but one based on the response of other men to an able, friendly and sincere personality whom they followed because they respected, admired and liked him.

The budding career of the college president was, however, interrupted for a period during the World War. His experience with problems of personnel was regarded as of too high value to the government to be neglected. Early in 1918 he was called to Washington to take charge of the industrial relations of the Quartermaster General's division of the War Department and soon after became assistant to the Secretary of War in charge of all industrial relations of the Department. His responsibility was that the production of supplies essential to the prosecution of the war should not be interrupted by labor controversies. His efforts were rewarded by a high degree of success, as shown by the following letter from Secretary of War Baker, when his services came to an end in December:

"I cannot allow you to sever your connection with the Department without expressing to you my appreciation of the work which you have done during the past year. You came to the Department nearly a year ago at a time when the problems of industrial relations in the plants producing supplies for the Department were daily growing more complex and serious. You inherited perhaps the most serious industrial controversy which has come before me at any time during the war. You succeeded in so stabilizing the situation that the Department's supply has proceeded without substantial interruption at any point from labor controversies and in relieving me of the annoying and difficult questions which must have arisen in the Department's labor policy. For this I feel a very real sense of personal gratitude."

That the requirements of the ideal college president are so exacting and so varied as to be, in their entirety, beyond the scope of any individual is a truism too hackneyed to be further emphasized. President Hopkins' own conception of the demands of the office, set forth after eleven years of experience in the position is contained in the advice given to his brother when the younger man was inaugurated President of Wabash College in 1927.* Beginning with the suggestion that no executive should take his work or himself so seriously as to impair his efficiency by that crippling point of view, none the less he asserted that the holder of the office should consider both the work and his own contribution to it as of vital importance. Leadership, he said, means influence, not mastery.

"Beware of ceremony and form so far as they are dehumanizing. Do not become oblivious of the attributes of human beings in seeking to learn the principles of educational methods. The college is no inanimate being, but an alert, vibrant organism; it is to such an organism that your loyalty is due. Do not allow yourself to be bemused or overpowered by the vastness of the opportunity; do not be weighed down by the heavy sense of obligation which, of necessity, will be yours; nor oppressed by an occasional sense of loneliness that will overcome you as among men who. of necessity, can see only the near-by objectives as desirable. You drive to attain goals far distant and not always sharply defined. In your position you cannot allow yourself contentment in any narrow view, nor ambition satisfied with any small accomplishment. A tantalizing, elusive but challenging opportunity is before you. The past is importani for its bearing on the present and the present for the light it may cast on the future. But the work of the college is always fundamentally for the benefit of a tomorrow about whose circumstances we can but inadequately know. Herein lies the difficulty. An institution tends to be stationary when it ought to be galvanized, cautious when it should be bold. Progress should be unceasingly sought even if the world does not esteem its prophets, but stones them."

More recently and more specifically, in response to the inquiry of one of his friends as to the requirements of the posi- tion, while, with all modesty, disclaiming the superior possession by himself o£ the qualities named, he set forth the following five conditions for maximum efficiency: the college president must know enough of educational problems to contribute intelligently to their solution; he must have sufficient acquaintance with business to conserve the resources of the institution; he must be at least something of an interesting and persuasive speaker; he must be able to develop contacts with the outside world that he may articulate the work of the institution advantageously to the society which it serves; he must have some talent for the tasks of personnel, for the smooth and unified operation of the institutiton under his charge. And he called attention to the most obvious defect of the modern administrator, as compared with his predecessor of the older school—that neither by previous training nor by available leisure is he likely to be in a position to assume properly the task of great spiritual leadership. To his mind the modern executive might be compared with Martha, busy with many things, rather than with Mary, the reflective and introspective personality, with the conclusion that, despite the real value of the latter, a world made up solely of Marys would have its disadvantages. The most fruitful activities of the president, he said, many of them irksome and tiresome, are of a nature seldom to be appreciated, or even known about, by those engaged in other branches of the institution. As a result, perhaps the greatest necessity for an occupant of the office is to be so thick-skinned that, without loss of patience, he may give free rein to an immense amount of diverse opinion and lack of understanding, even among his most loyal supporters, and may expect and accept in silence a large amount of criticism as inevitable. It is upon such principles that President Hopkins has based the fruitful leadership of the last twenty-five years.

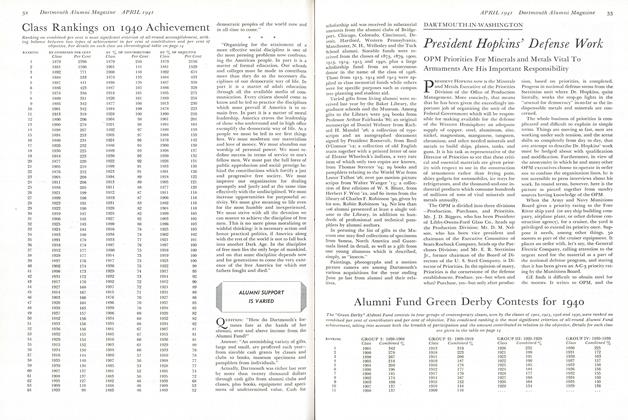

Space does not permit the accomplishment of that period in other than the merest outline. In 1916 the productive endowment of the College was valued at $4,184,000 and that of the educational plant at $1,769,000. The annual expenditure was $541,407 of which 47% was for teaching purposes—instruction and library expenditures. In 1940 the boo"k value of the invested funds was $18,031,000, that of the educational plant, $7,533,000, and the annual expenditures, $1,932,000, of which nearly 64% was devoted to teaching purposes.

This rapid increase was the result of no spontaneous, unnurtured development, but the outcome of the hardest kind of work. In fact, at times an acute financial crisis seemed to impend. Thus almost immediately after the accession of the new President, with American entry into the World War, student attendance dropped to less than half its previous figure and a College overhead geared to former enrollment was thrown hopelessly out of adjustment with possible income from the reduced student body. The problem was met courageously, drastic economies were instituted, not, however, at the expense of faculty salaries, which were, in fact, increased to meet the rapidly rising cost of living, money was obtained in larger amounts and from new sources, and the period of crisis was weathered with no accumulated College deficit. Particularly helpful at this time was the assistance of Mr. Tuck. Originally he was somewhat doubtful of the qualifications of the new President and the first visit of that executive to Paris had its amusing aspects in the wary uncertainty with which the two men regarded one another. But here, as elsewhere, that feeling passed as if by magic, the men found themselves especially congenial and a tie of the strongest personal affection soon united them—Mr. Tuck, his immediate family largely gone, regarding the head of the College almost as a son and the institution itself as his own responsibility, without, however, in the slightest way interfering in its management.

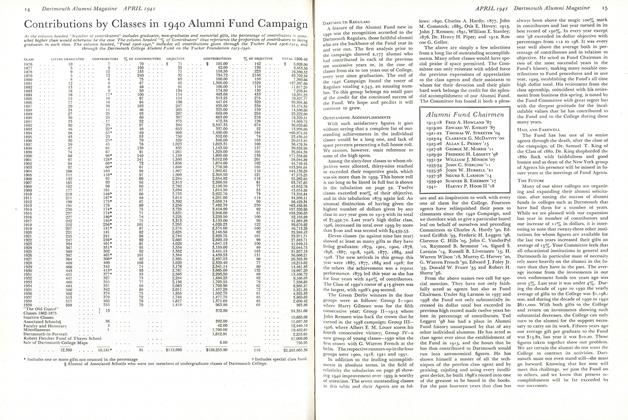

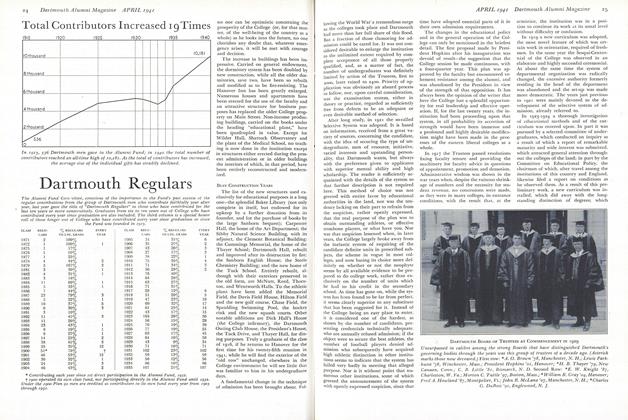

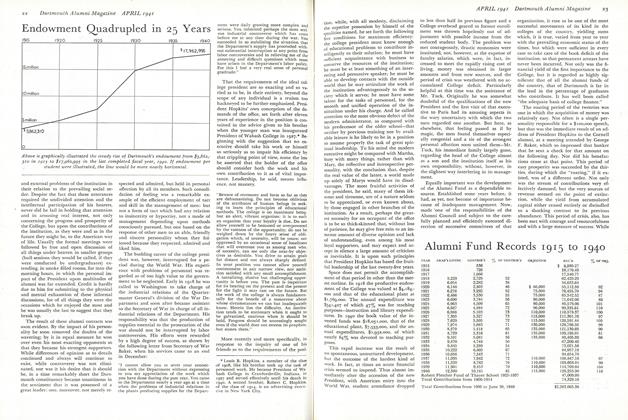

Equally important was the development of the Alumni Fund as a dependable resource. Established some years before, it had, as yet, not become of importance because of inadequate management. Now, made 'one of the responsibilities of the Alumni Council and subject to the carefully planned and efficiently executed direction of successive committees of that organization, it rose to be one of the most successful movements of its kind in the colleges of the country, yielding sums which, it is true, varied from year to year with the prevailing economic status of the times, but which were sufficient in every case to take care of the book deficit of the institution, so that permanent arrears have never been incurred. Not only was the financial yield of the first importance to the College, but it is regarded as highly significant that of all the alumni funds of the country, that of Dartmouth is far in the lead in the percentage of graduates who contribute. It has well been called "the adequate basis of college finance."

The roaring period of the twenties was one in which the acquisition of money was relatively easy. Not often is a single personality responsible for a $ 100,000 speech, but that was the immediate result of an address of President Hopkins to the Cornell alumni, at a meeting attended by George F. Baker, which so impressed that banker that he sent a check for that amount on the following day. Nor did his benefactions cease at that point. This period of easy prosperity was succeeded by the thirties, during which the "roaring," if it existed, was of a different order. Not only was the stream of contributions very effectively dammed, but the very sources of revenue seemed on the point of extinction, while the yield from accumulated capital either ceased entirely or dwindled to a shocking contrast to its previous abundance. This period of crisis, also, has been met with courage and resourcefulness and with a large measure of success. While no one can be optimistic concerning the prosperity of the College (or, for that matter, of the well-being of the country as a whole) as he looks into the future, no one cherishes any doubt that, whatever emergency arises, it will be met with courage and decision.

The increase in buildings has been impressive. Carried on general endowment, the dormitory system has been doubled by new construction, while all the older dormitories, save two, have been so rebuilt and modified as to be fire-resisting. The Hanover Inn has been greatly enlarged. Numerous houses and apartments have been erected for the use of the faculty and an attractive structure for business purposes has replaced the older College property on Main Street. Non-income producing buildings, carried on the books under the heading "educational plant," have been quadrupled in value. Except for Wilder Hall, Shattuck Observatory and the plant of the Medical School, no teaching is now done in the institution except in structures either erected during the present administration or in older buildings the interiors of which, in that period, have been entirely reconstructed and modernized.

BUSY CONSTRUCTION YEARS

The list of the new structures used exclusively for educational purposes is a long one—the splendid Baker Library (not only complete in itself, but endowed for its upkeep by a further donation from its founder, and for the purchase of books by the large Sanborn bequest); Carpenter Hall, the home of the Art Department; the Silsby Natural Science Building, with its adjunct, the Clement Botanical Building; the Cummings Memorial, the home of the Thayer School; Dartmouth Hall, rebuilt and improved after its destruction by fire; the Sanborn English House; the Steele Chemistry Building; and the new home of the Tuck School. Entirely rebuilt, although with their exteriors preserved in the old form, are McNutt, Reed, Thornton, and Wentworth Halls. To the athletic plant have been added the Memorial Field, the Davis Field House, Hilton Field and the new golf course, Chase Field, the Spaulding Swimming Pool, the hockey rink and the new squash courts. Other notable additions are Dick Hall's House (the College infirmary), the Dartmouth Outing Club House, the President's House, the Tuck Drive, and Thayer Hall, for dining purposes. Truly a graduate of the class of 1916, if he returns to Hanover for the first time for his twenty-fifth reunion in 1941, while he will find the exterior of the "old row" unchanged, elsewhere in the College environment he will see little that was familiar to him in his undergraduate days.

A fundamental change in the technique of admission has been brought about. Following the World War a tremendous surge to the colleges took place and Dartmouth had more than her full share of this flood. But a fraction of those clamoring for admission could be cared for. It was not considered desirable to enlarge the institution to the unlimited extent required by complete acceptance of all those properly qualified, and, as a matter of fact, the number of undergraduates was definitely limited by action of the Trustees, first to 2000, later raised to 2400. Priority of application was obviously an absurd process to follow, nor, upon careful consideration, was the examination system, either in theory or practice, regarded as sufficiently free from defects to be an adequate or even desirable method of selection.

After long study, in 1931 the so-called Selective System was adopted. It is based on information, received from a great variety of sources, concerning the candidate, with the idea of securing the type of undergraduate, men of resource, initiative, varied interests and upstanding personality, that Dartmouth wants, but always with the preference given to applicants with superior mental ability and high scholarship. The reader is sufficiently acquainted with the details of the system so that further description is not required here. This method of choice was not greeted with entire favor by educational authorities in the land, nor was the tendency lacking on their part to refrain from the suspicion, rather openly expressed, that the real purpose of the plan was to obtain outstanding athletes, or effective trombone players, or what have you. Nor was that suspicion lessened when, in later years, the College largely broke away from the inelastic system of requiring of the candidate definite units in prescribed subjects, the scheme in vogue in most col- leges, and now basing its choice more def- initely on whether or not the neophyte seems by all available evidence to be pre- pared to do college work, rather than ex- clusively on the number of units which he had to his credit in the secondary school. As time has gone on, while the sys- tem has been found to be far from perfect, it seems clearly superior to any substitute that has been suggested for it. Instead of the College being an easy place to enter, it is considered one of the hardest, as shown by the number of candidates, pre- senting credentials technically adequate, who are annually refused admission; if the object were to secure the best athletes, the number of football players denied admission who subsequently have acquired high athletic distinction in other institutions seems to indicate that the system has failed very badly in meeting that alleged purpose. Nor is it without point that numerous other institutions, some of which greeted the announcement of the system with openly expressed suspicion, since that time have adopted essential parts of it in their own admission requirements.

The changes in the educational policy and in the general operation of the College can only be mentioned in the briefest detail. The first proposal made by President Hopkins after his inauguration was devoid of result—the suggestion that the College session be made continuous, with a four-quarter year. This plan was approved by the faculty but encountered vehement resistance among the alumni, and was abandoned by the President in view of the strength of that opposition. It has always been the opinion of the writer that here the College lost a splendid opportunity for real leadership and effective operation. If, for the last twenty years, the institution had been proceeding upon that system, in all probability its accretion of strength would have been immense and a profound and highly desirable modification might have been made in the processes of the eastern liberal colleges as a whole.

In 1917 the Trustees passed resolutions fixing faculty tenure and providing the machinery for faculty advice in questions of appointment, promotion and demotion. Administrative wisdom was shown in the war years when, despite the ruinous shrinkage of numbers and the necessity for student revenue, no concessions were made, as they were in many colleges, in entrance conditions, with the result that, at the armistice, the institution was in a position to continue its work at its usual level without difficulty or confusion.

In 1919 a new curriculum was adopted, the most novel feature of which was certain work in orientation, required of freshmen. In the same year the Sesqui-Centennial of the College was observed in an elaborate and highly successful ceremonial. At about the same time the system of departmental organization was radically changed, the excessive authority formerly residing in the head of the department was abandoned and the set-up was made more democratic. The years just previous to 1921 were mainly devoted to the development of the selective system of admission, already referred to.

In 1923-1924 a thorough investigation of educational methods and of the curriculum was entered upon. In part it was pursued by a selected committee of undergraduates, which conducted an inquiry as a result of which a report of remarkable maturity and wide interest was submitted, which attracted general attention throughout the colleges of the land; in part by the Committee on Educational Policy, the chairman of which, after travel among the institutions of this country and England, likewise filed a report on conditions as he observed them. As a result of this preliminary work, a new curriculum was installed, which did away with the longstanding distinction of degrees; which lessened arbitrary requirements and increased the demand for thorough acquaintance with someone major subject, selected by the student; which set up a system of comprehensive examinations as prerequisite for the degree; and which established, in certain departments, honors courses for students of the higher grades. In the same year compulsory chapel was abolished as no longer serving its destined purpose. Likewise at this time fraternity interference with the work of freshmen was eliminated by presidential fiat barring members of that class from such organizations. In 1929 the system of senior fellowships, granting complete freedom in their senior year to certain selected students, was instituted.

In 1935 an elaborate social survey was undertaken by a special committee, with the result, first, of the construction of Thayer Hall to provide effective and comfortable eating facilities, at that time not universal in Hanover, and, second, of directing the attention of local chapters of national fraternities to the question of whether they had any excuse for existence. Improved conditions in these organizations soon tended to prevail, while the national fraternities themselves, after their first roar of indignation, set themselves to a more sober consideration of their effect, whether beneficial, neutral or actually injurious, on the institutions of which they are a part. In the same year a committee investigating health conditions evolved a scheme of health insurance for undergraduates which has worked to their great physical advantage. In 1937 the program of the departments of social science was radically altered and in the same year an investigation of College publications generated for a time considerable heat, but eventually brought forth a settlement which gives some promise of good. The scheme advanced in 1938 for the erection of a great auditorium and theater, with the promise that thereby Hanover would become a dramatic, musical and radio center, has as yet had no fruitful result because of lack of funds.

It is not to be supposed that the President is sojely responsible for the details of all this activity. Like all real executives, he has the art of delegating authority. But the initiative for these movements came from him, he was the center around which they revolved, and to him, more than to anyone else, is due the credit for their accomplishment.

When the question of athletics is raised, the writer is somewhat at a loss. The sight of a college president, braving the force of a stormy New Hampshire November to observe certain selected men do violent things, sometimes'to a football, more often to each other, when a person of his age and dignity might be toasting his toes before a comfortable fire; the view of that same president, in company with some perfervid athletic alumnus, solicitously following the contortions of eleven men in so-called secret practice at a time when he might be holding deep philosophical discourse with the Professor of Sanskrit or even discourse, obviously less profound but still of weight, with a properly selected member of the Department of Chemistry; when such conduct is observed, the approval of the writer is not entirely enthusiastic. The depressing feature of the situation is that the sympathy of 99.44% of the readers of this article is sure to be with the President and not with the writer. However that may be, President Hopkins is as enthusiastic and devoted a follower of sport as is the most volatile freshman.

Varied has been his experience of college football since he first came to Hanover Plain in 1897. In these years at times only the good sense of the College authorities (most of all, his own) has rejected without question pressing invitations to participate in the tawdry tinsel and commercialism of the Rose Bowl; at other times the team would hardly have been welcomed even to a cracked China Bowl picked up in a Harlem dump. But the viewpoint of the head of the institution as to the proper place of athletics in an educational institution is entirely sane—college students playing games and not hired athletes posing as college students. This view he holds despite the fact that in some institutions in all parts of the land and all institutions in some parts of the land the second condition is the one which prevails, apparently with the approval, not only of the general public, but of the authorities of the institutions themselves. Much has he done, often in ways which could achieve no publicity, to bring about more satisfactory conditions in college sport. In 1927, with the professed purpose to save football, which he regarded as eminently worth saving, he proposed a plan by which active varsity competition should be limited to sophomores and juniors; that each contest between rival institutions should consist of two games played by two teams of each college, one to be contested on the home field of each; and that all coaching should be done by undergraduates, presumably seniors.

The plan cut at the heart of the present regime of commercialized sport and was received with loud haw-haws by nearly all the devotees of the existing machine. But, on the basis of the definition above, "college students playing games," it does not seem to be without merit.

The reproach that a few men in college play games while all the rest watch, he has endeavored to remove by the institution of compulsory recreation for freshmen and sophomores, with adequate facilities for all branches of sport. To the writer the coupling of the words "compulsory" and "recreation" has always seemed to be a trifle ironical, but even he must admit that the playing fields of the College in these days show a picture of voluntary athletic activity (in his mind the only type worth while) not presented at Dartmouth since the days so long ago when the whole undergraduate body assembled on the green each afternoon with the purpose of kicking a football, when opportunity presented, but, in any case, of kicking their opponents in the shins when the ball, at any stage of the contest, was not favorably located.*

The fundamental conception of the liberal college held by the President was brought out clearly in his inaugural address and has been the central theme of all his subsequent utterances. To him the institution has its excuse for being only in the satisfactory performance of definite duties to the community and to the social order, in the results which it endeavors to attain in the students under its charge. That its purpose may be attained, it must ever be on the watch to adapt its policies to the changing conditions of the times. Unlike the university, the college is to be regarded as an institution which is the terminus of the formal education of the majority of those entering its doors. Attendance is to be regarded as a privilege and one justified only if full use of its opportunities is made by its undergraduates. Its constant endeavor should be to develop the whole man. Intellectually its students should form useful habits: the habit of thinking for themselves; the habit of proceeding under their own motive power; the habit of alertness and discrimination; the habit of recognizing sophistry and of resistance to the argument of mere self-interest. Its graduates should be capable of intelligent and altruistic leadership, if powers of leadership are within them; but if such gifts are not their possession, they should have the discrimination to select the best leadership and to become useful followers of such a cause. But progress should not be limited to the intellectual side. Physical development should be stressed to match intellectual competence; the overwhelming power of emotional impulses should be recognized and should be so directed and stimulated that it is turned to serviceable ends; ethical standards should be nurtured sympathetically and intelligently; and the place of real religion (as distinguished from mere dogmatism) should be given its due recognition as the central motive in the life of man.

A concise statement of his conception of the purpose of the College is contained in the last paragraph of his opening address for the year 1927-1928.

"In conclusion I wish my final word today to be a plea to the men of the undergraduate body not to fall into easy misconceptions of what the College wishes to accomplish or of the significance of the process by which it works. It seeks to be a stimulus to intellectual awakening and heightened mental power. It aspires to be the agency by which men are induced to think. It cajoles ability, not to flatter it, but to give it self-confidence. It flays ignorance, not in contempt for those subject to it, but in solicitude for those who may avoid it. It questions conventionality, not because convention is predominantly wrong, but because convention is not always right. It challenges belief, not that belief shall be destroyed, but that it shall be made strong."

And so, for twenty-five years, in opening addresses to the undergraduate body, in thoughtful utterances to groups of alumni, in manifold speeches to organizations not connected with the College, he has reiterated the validity of these principles and has made of them the widest variety of applications, fitted to the particular demands of the times. Always he has had an audience, always has he been listened to with interest and respect, always his influence upon those whom he has addressed has been definite and profound. In particular, his opening addresses to the undergraduates have been quoted and commented upon from one end of the land to the other—no previous President of the institution has been so successful in the extent of his appeal. He has been referred to as an eminently "quotable man,"as, indeed, he is. As a result, widespread interest, it may be controversy, oftentimes approval, sometimes disapproval, but always comment has followed his productions for many years. But a few of the debatable questions which he has raised can be mentioned here.

In 1922 a demand was made upon him, either as President of Dartmouth or as Trustee of Worcester (it is not clear which), by a group of extremists of his own Baptist denomination that he should weed out the heretical elements of his teaching force—this at a time when the fundamentalist movement had attained impressive, although temporary, importance. This appeal gave him an opportunity in a public letter sharply to reprove the spirit of bigotry and intolerance thus exhibited, to protest against the movement in a denomination ordinarily free from ecclesiastical dictation, and to defend freedom of teaching and of thought. At the same time he showed his own lack of dogmatism by welcoming to a Dartmouth platform William Jennings Bryan, then the leading champion of fundamentalism.

In the same year in his opening address he made the blunt statement that too many men were going to college.

"There is such a thing as an aristocracy of brains, made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually eager, to whom increasingly the opportunities of higher education ought to be restricted, if democracy is to become a quality product rather than simply a quantity one, and if excellence and effectiveness are to displace the mediocrity toward which democracy has such a tendency to skid."

This utterance seems sensible enough, but the phrase "aristocracy of brains" caught the public eye and became the occasion of nation-wide comment. It was sharply attacked, particularly by the proponents of the state universities and the more extreme of the public school executives, by whom the word "aristocracy" was assumed to have only an evil meaning and who stoutly maintained that any moron who could propel himself to a university should there receive assistance, financial and otherwise, to obtain an "education."

In 1923 he stressed the fundamental difference between education and training and asserted that the liberal college must stand predominantly for the former, rather than specialize on the latter. This topic recurred in 1931 when he declared that the aim of the institution should be the development of the intelligent man (intelligence being the beginning of wisdom) rather than the man who should be merely widely informed. In 1924 the newspapers reported that in a speech in Chicago he said that he would be glad to welcome Lenin and Trotzky as members of the Dartmouth faculty, if he could secure their services. What he actually said was this: "If those responsible for a theory of government which now dominates an eighth of the earth's surface and a great host of her people were available for the explanation of their theories to the undergraduate body, I should be glad to have the students hear them and to have them form their judgment as to the danger or merits of Bolshevism on the basis of direct evidence rather than through the inconsistent and contradictory pronouncements of anti-Bolshevik propaganda."

This also seems a reasonable position if the College is to be regarded as a liberal institution which repudiates the idea of maintaining a "sheltered" undergraduate body, but, of course, it encountered opposition, .expressed in the most violent terms, from the dourly conservative element. Parenthetically it may be said that at this time, when the Russian experiment seems to have degenerated into an ordinary type of dictatorship, run for and by a single person for purposes having no obvious connection with social progress, it may be doubted if the President would think it of educational value for the undergraduates of the College to be privileged to listen to a representative of that dictator, to present his "theories."

In 1925 his opening address, widely and somewhat erroneously commented upon, made reference to certain necessary limitations in the participation of the alumni in College affairs. In 1928, at the University Club in Boston, he responded in an emphatic manner to the widely publicized complaint then recently made by Clarence Barron that the New England college is a "curse" because it does not respond sufficiently to the material needs of the section. He definitely denied that the function of the college should be of this limited order and again stated what he conceived to be its true purpose.

In 1931 he was the second of the easterr college presidents (President Butler had been against the system from the first) to announce his opposition to the continuance of national prohibition. Having been quiescent for a long period with the hope that the policy would really become effective, now, becoming convinced that its defects obviously outweighed its advantages, he asserted that no further hesitation was possible.

This statement of position aroused the most widespread discussion, with praise or blame awarded according to the predilections of the commentator. It was one of the first attacks on the system coming from one sympathetic with the purpose of the movement and about whose good judgment and ethical sense there could be no question, and it led the way for many others. Amusing is the reaction to this declaration of the then Chief Executive of the nation, who, when the President of the College was a guest at the White House, chiding him rather sharply upon his attitude, asserted that his own special facilities of access to public opinion, far greater than those of any other person, revealed overwhelming favor for the system, which, he predicted, never would be repealed. Events in the immediate future indicated that the great engineer might well have devoted some of his professional skill to the pipe line which he evidently relied upon for such information. The leakiness of that mechanism, it is now obvious, must have been deplorable.

In his address in 193 a President Hopkins pointed out the danger to the nation coming from that perverted sense of equality which results in unsatisfactory leadership, prone to yield to the demands of special privilege. He complained of the "tending down" of democracy, resulting in the lack of discipline and the elevation of mediocrity. In 1935 he set forth the view that great erudition may and often is accompanied by a child-like conception of what actuates the mind of man collectively. And at this time he was one of the first to point out the power of movements abroad, coming from the unthinking but highly effective self-discipline of the proletariat of the dictatorships, and the danger to democracy presented by the competition of nations thus organized, unless similar discipline, based not on compulsion but on free thought, can there be established. In recent years, in consonance with his conception of the needs of the times, his stress has been on discipline rather than on freedom—the latter quality, so he fears, as applied by the youth of the day having degenerated into a lack of a sense of responsibility and avoidance of that which is irksome, including the irksomeness of any form of straight thinking which leads to conclusions that are unpleasant. In his opening address of 1940 he even predicted that, in the present crisis, a temporary sacriifice of democracy might have to be endured in order that democracy permanently might survive.

The association of the President with other activities than those of the College have been numerous. Very likely the writer has not been able to detect all of them so that the list given here may be incomplete. His work with the War Department in Washington has already been mentioned. In 1931 he was member of a New Hampshire commission to study the question of employer's liability and workmen's compensation. Many times suggested for public office and pronounced by the poll conducted by the Granite Monthly in 1923 to be the "leading New Hampshire man," he has always declined to enter politics as a candidate, although he served as Republican presidential elector from New Hampshire in 1928. In the business world he is a director of the Boston & Maine Railroad and of the National Life Insurance Company of Montpelier (Vermont). In 1933 he served effectively as arbitrator in the settlement of the bitter and long-continued labor dispute in the granite industry at Barre. In the same year he conducted an investigation of the school system of Puerto Rico, as the representative of the War Department. He is now a Trustee of Phillips-Andover Academy and of the Newton Theological Institution, and has held a similar position at Worcester Academy. He was Trustee and President of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation and Trustee of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, and is now a member of the Rockefeller Foundation and likewise a member (chairman since 1939) of the General Education Board. He has been Trustee of the Industrial Relations Counselors (1927-1935), of the Brookings Institution (1926-1930), a member of the Foreign Bondholders Protective Council (1933-1935), of the New England Council (1929-1933), of the Board of Visitors of the United States Naval Academy (1937-1938), and councillor of the National Industrial Conference Board (1930-1933). He declined the position of President of the University of Chicago in 1922. His lectures on the Jayne Foundation, delivered at Philadelphia in 1925, have been published in book form and a further volume from his pen, a lecture delivered on the War Me'morial Foundation at Milton Academy, entitled Educationand Life, appeared in 1930. He writes an occasional magazine article and is in constant demand as a speaker before educational institutions and a wide variety of other groups. To date he has acquired fourteen honorary doctorates, so that some of his ribald friends suggest that he appear at Commencement attired in the scarlet gown coming from McGill, with all fourteen hoods attached—a proceeding which surely would add color to the occasion. In politics, registered as a Republican, occasionally he jumps the fence, usually meeting the writer on the way over in the opposite direction —from which the conclusion should be derived that he is usually wrong in such matters—or should it?

Since the above was written, new evidence is at hand of the esteem in which President Hopkins' services are regarded in times of national crisis. Early in January he was appointed to the chairmanship of the iron and steel priorities committee, under the Defense Priorities Division, headed by Edward R. Stettinius, with the understanding that he is to serve as executive officer of the new minerals and metals priority section, heading the various groups advisory to the recently organized Office of Production Management. This work involves solution of the most perplexing and complicated problems, and the reconciliation of the most diverse and conflicting interests, in the attempt to do away with bottlenecks which so much impede satisfactory national defense. So his activities now and in the immediate future are to be largely in Washington, where the value of his services surely will equal that of his contributions to the settlement of the crisis of twenty-five years ago.

Discussion of the character of President Hopkins would be incomplete, however, if consideration were not given to his intimate personal qualities. It is, indeed, in no measure through those gifts of personality that his powers of leadership and vision are most directly made effective. Of course he is not without his share of the weaknesses with which man is afflicted, but those defects are counteracted by a sense of balance which prevents them from becoming elements of obstruction. Thus not seldom he is impatient and sometimes becomes irritated at the efforts of others directed against policies which he has carefully formulated. When the member of the Faculty who, perhaps, is the most strident, persistent and obstinate of all the teaching force, has opposed in faculty meeting, pertinaciously and at length, some plan which the President regards as highly promising, the next morning he may be greeted by the head of the College with an ominous reference to a certain heavy glass inkstand on the President's desk in the Faculty Room, its virtues as a missile are set forth together with an explanation of the superb self-control which caused the presiding officer to refrain from using it for that purpose on the preceding evening and the hope, which is not a confident one, that that self-control will continue in the future in the face of similar obstructive tactics. Of course the faculty member in question is the only one who is told of the dangerous position in which he stood and still stands. That is how the writer knows about it. fn truth, impatience is manifested only in jocular ways like this and never becomes evident in such a manner as to give rise to serious differences, or, incidentally, to hamper the success of projects which the President wishes to foster.

Sometimes he is regarded by his friends as a bit exuberant in his enthusiasm for certain men and measures, but seldom, when actual decisions of importance are to be made, is that enthusiasm allowed to stand in the way of the objective consideration of those questions. Sometimes he becomes discouraged, but his sense of balance and perspective is such that these periods of depression are not lasting. Sometimes he makes mistakes in his judgment of men, as, in particularly flagrant cases, he has been the first ruefully to admit, but, in general, that judgment is excellent. In particular, he possesses what might almost be described as a genius for detecting in persons qualities which no one else, least of all those men themselves, imagined that they possessed and in giving opportunity for the utilization of these qualities to the satisfaction and profit of all concerned. Sometimes he is antipathetic to personalities, but he is always the first to recognize merit, if it exists, in those who are uncongenial to him and, with meticulous care, to see that such merit is cherished by the institution, used to its full capacity and granted a generous reward.