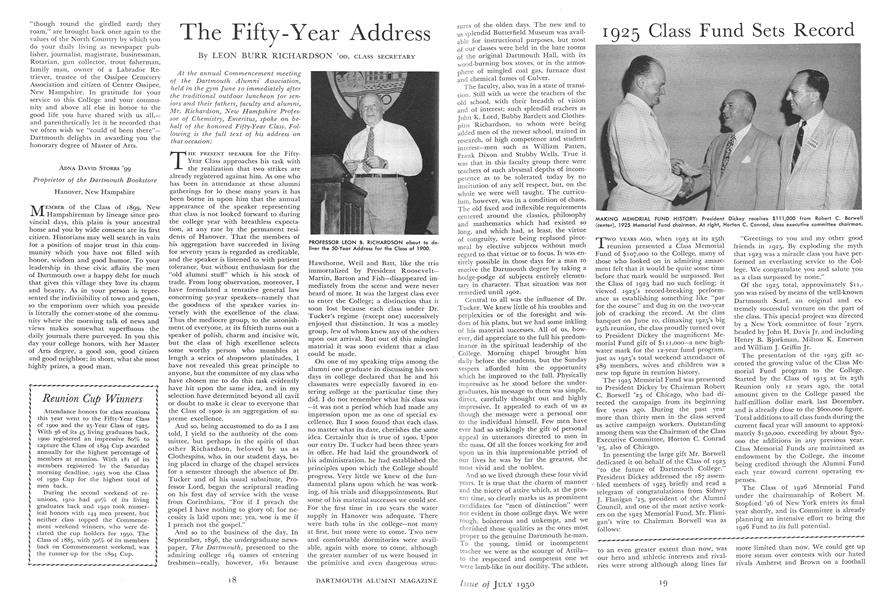

At the annual Commencement meetingof the Dartmouth Alumni Association,held in the gym June 10 immediately afterthe traditional outdoor luncheon for seniors and their fathers, faculty and alumni,Mr. Richardson, New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry, Emeritus, spoke on behalf of the honored Fifty-Year Class. Following is the full text of his address onthat occasion:

THE PRESENT SPEAKER for the FiftyYear Class approaches his task with the realization that two strikes are already registered against him. As one who has been in attendance at these alumni gatherings for lo these many years it has been borne in upon him that the annual appearance of the speaker representing that class is not looked forward to during the college year with breathless expectation, at any rate by the permanent residents of Hanover. That the members of his aggregation have succeeded in living for seventy years is regarded as creditable, and the speaker is listened to with patient tolerance, but without enthusiasm for the "old alumni stuff" which is his stock of trade. From long observation, moreover, I have formulated a tentative general law concerning 50-year speakers—namely that the goodness of the speaker varies inversely with the excellence of the class. Thus the mediocre group, to the astonishment of everyone, at its fiftieth turns out a speaker of polish, charm and incisive wit, but the class of high excellence selects some worthy person who mumbles at length a series of shopworn platitudes. I have not revealed this great principle to anyone, but the committee of my class who have chosen me to do this task evidently have hit upon the same idea, and in my selection have determined beyond all cavil or doubt to make it clear to everyone that the Class of 1900 is an aggregation of supreme excellence.

And so, being accustomed to do as I am told, I yield to the authority of the committee, but perhaps in the spirit of that other Richardson, beloved by us as Clothespins, who, in our student days, being placed in charge of the chapel services for a semester through the absence of Dr. Tucker and of his usual substitute, Professor Lord, began the scriptural reading on his first day of service with the verse from Corinthians, "For if I preach the gospel I have nothing to glory of; for necessity is laid upon me; yea, woe is me if I preach not the' gospel."

And so to the business of the day. In September, 1896, the undergraduate newspaper, The Dartmouth, presented to the admiring college 164 names of entering freshmen—really, however, 161 because

Hawthorne, Weil and Batt, like the trio immortalized by President Roosevelt-Martin, Barton and Fish—disappeared immediately from the scene and were never heard of more. It was the largest class ever to enter the College; a distinction that it soon lost because each class under Dr. Tucker's regime (except one) successively enjoyed that distinction. It was a motley group, few of whom knew any of the others upon our arrival. But out of this mingled material it was soon evident that a class could be made.

On one of my speaking trips among the alumni one graduate in discussing his own days in college declared that he and his classmates were especially favored in entering college at the particular time they did. I do not remember what his class was —it was not a period which had made any impression upon me as one of special excellence. But I soon found that each class, no matter what its date, cherishes the same idea. Certainly that is true of 1900. Upon our entry Dr. Tucker had been three years in office. He had laid the groundwork of his administration, he had established the principles upon which the College should progress. Very little we knew of the fundamental plans upon which he was working, of his trials and disappointments. But some of his material successes we could see. For the first time in 120 years the water supply in Hanover was adequate. There were bath tubs in the college—not many at first, but more were to come. Two new and comfortable dormitories were available, again with more to come, although the greater number of us were housed in the primitive and even dangerous structures of the olden days. The new and to us splendid Butterfield Museum was available for instructional purposes, but most of our classes were held in the bare rooms of the original Dartmouth Hall, with its wood-burning box stoves, or in the atmosphere of mingled coal gas, furnace dust and chemical fumes of Culver.

The faculty, also, was in a state of transition. Still with us were the teachers of the old school, with their breadth of vision and of interest; such splendid teachers as John K. Lord, Bubby Bartlett and Clothespins Richardson, to whom were being added men of the newer school, trained in research, of high competence and student interest—men such as William Patten, Frank Dixon and Stubby Wells. True it was that in this faculty group there were teachers of such abysmal depths of incompetence as to be tolerated today by no institution of any self respect, but, on the whole we were well taught. The curriculum, however, was in a condition of chaos. The old fixed and inflexible requirements centered around the classics, philosophy and mathematics which had existed so long, and which had, at least, the virtue of congruity, were being replaced piecemeal by elective subjects without much regard to that virtue or to focus. It was entirely possible in those days for a man to receive the Dartmouth degree by taking a hodge-podge of subjects entirely elementary in character. That situation was not remedied until 1902.

Central to all was the influence of Dr. Tucker. We knew little of his troubles and perplexities or of the foresight and wisdom of his plans, but we had some inkling of his material successes. All of us, however, did appreciate to the full his predominance in the spiritual leadership of the College. Morning chapel brought him daily before the students, but the Sunday vespers afforded him the opportunity which he improved to the full. Physically impressive as he stood before the undergraduates, his message to them was simple, direct, carefully thought out and highly impressive. It appealed to each of us as though the'message were a personal one to the individual himself. Few men have ever had so strikingly the gift of personal appeal in utterances directed to men in the mass. Of all the forces working for and upon us in this impressionable period of our lives he was by far the greatest, the most vivid and the noblest.

And so we lived through these four vivid years. It is true that the charm of manner and the nicety of attire which, at the present time, so clearly marks us as prominent candidates for "men of distinction" were not evident in those college days. We were rough, boisterous and unkempt, and we cherished those qualities as the ones most proper to the genuine Dartmouth he-man. To the young, timid or incompetent teacher we were as the scourge of Attila to the respected and competent one we were lamb-like in our docility. The athlete, to an even greater extent than now, was our hero and athletic interests and rivalries were strong although along lines far more limited than now. We could get up more steam over contests with our hated rivals Amherst and Brown on a football budget of S3000 a season than can be done today when such expenditures amount to $30,000 or $300,000 or $3,000,000 or whatever the sum really is. We had no automobiles and so had perforce to remain in Hanover; we had no movies and so had the time free which is now, apparently, required daily by prescription of all undergraduates for attendance on this form of alleged entertainment; we had no girls, a situation which we attempted to remedy in a measure by the institution in our junior year for the first time in the College of a week-end of social festivities in May—a custom which has continued ever since. Loyal as the secretary has tried to be to his class, in his long years of faculty service observation of this festivity has raised some doubt in his mind as to its being entirely beneficent in its influence or a credit to the class as its originator. Palaeopitus also dates from our class, in its senior year. Some of us studied hard and learned a great deal; some of us, mentally gifted, learned a great deal without studying hard; some learned as much as they thought they needed and devoted much time to other than scholastic activities, often of distinct value; some sat and talked; some sat and meditated and some just sat. We had our political contests and personal quarrels, we formed lifelong friendships, and in general we had fun. Even as all classes in the history of the College. And finally in 1900, 122 of us received our degrees from the hands of Dr. Tucker. In addition 43 non-graduates have always been reckoned as integral members of the group, making our total 165.

Upon graduation we set about the task of making a homogeneous class. Such an attempt depends for its success upon good leadership and that leadership we have had in full measure. During our whole alumni existence of fifty years we have had but one president, Walter Rankin, tirelessly devoted, industrious, attentive to detail, indispensable to our class life. Since 1902 Clarence McDavitt has been trustee of the class fund, treasurer, class agent and what have you in the financial way; highly efficient in that capacity, but, more than that, the active and helpful friend of us all. From 1913 to his death in 1935 Natt Emerson was our secretary; wise, sympathetic, kindly, understanding, the prince of secretaries. These men, an effective team, have welded the class into the unified, homogeneous group that now exists.

That unity is real. Of the 64 men who still survive all are in frequent communication with us save four, three of whom were with us only for short periods. With the families of 85 of the 101 who have gone from us we are in touch, and of them 74 have an interest in the class sufficient to bring from them memorial subscriptions to the class fund. Since 1914 (save in the war years 1942 and 1943 (when transportation difficulties intervened) we have had annually what amounts to a reunion, although called by the name of round-up, in those years when no official reunion is recognized by the College. At first these June weekends were held in various places in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, but the last thirteen o£ them (to which, incidentally, our wives, much as we love them, are never invited) have had a settled abode at Kezar Lake, North Sutton, N. H. The attendance in recent years has approached and sometimes passed 50% of the living membership of the class.

Despite the fact that we have among us no men of really large wealth, we have a modest pride in our financial contributions to the College. In 1903, through the suggestion of Clarence McDavitt, we established the 1900 Class Fund, the goal of which was, through annual gifts carefully planned, to have available for the purposes of the College the sum of $10,000 on the twenty-fifth anniversary of our graduation. Some ten or more years later, when the general Alumni Fund on the Tucker Foundation was instituted, our plan was working so well that it was considered unfortunate to disturb it, so that to this day our individual gifts are made technically to the Class Fund, and the yield to the Alumni Fund comes from an appropriation derived from it. All class expenses are also paid from the Class Fund. At the expiration of the prescribed period the amount available was more than six times the sum which had been planned, so that it was possible to devote $63,000 to the construction of the 1900 Outing Club House. To this in later years $85OO was added for enlargement of the house. The total contributions to the College from the fund, up to and including 1950, have been $133,781, with a list of contributors which this year includes all but one of the living graduates, all but three of the living nongraduates and 74 representatives of the families of our 101 deceased members. All this has been done under the leadership of Clarence McDavitt. Beyond this fund the College has received for other purposes, either in individual gifts or those of groups for special purposes, amounts which raise our total contributions to over $197,000. And the end, we trust, is not yet.

1900 is not distinguished for the resounding fame of its members. We have in our ranks no eminent statesman or even politician, no world-shaking prophet, no tuneful poet, no profound philosopher. The words of the song of our youth "Some day you may be pres-i-dent or gineral in the army" have not justified themselves with us. But the secretary, who should be in the best position to know the careers of his classmates and to estimate their usefulness, when he does so has no occasion for repining or regret. With hardly an exception they have done well the work of the day, with devotion and fidelity they have served the circle, large or small, of those with whom they have been in contact. Only a few are named here, all selected from the ranks of those who have gone before us, chosen more or less at random but representative of the group as a whole. We think of the physicians, early victims of fate such as Bill Clark and Eddie Dearborn, ever faithful to the exhausting duties and killing pace of a rural New Hampshire practice, and of those other physicians, John Long, Bill Stickney, Henry Weston, whose lives were brought to premature ends by the physical exertion and mental strain coming from army service as surgeons in the first World War. We think of the teacher, Frank Howe, spending a long life in the actual process of instruction, disdaining the factitious attractions of- greater financial profit of the educational administrator, but remaining a continuing influence upon generations of adolescents: of that other teacher, Franklin Lewis, the thoughtful and productive head of a great educational institution. We think of the clergyman, Francis Bradley, brilliant as an undergraduate but sadly neurotic in temperament, returning from the training of the Catholic Church in Rome, calm, poised, self possessed, plunging into the work of that church among the immigrants of a great mill city with an energy and self-sacrificing devotion which carried him off in a brief twenty years. We think of the successful business man, Natt Emerson, impressing all about him with his gentleness, sympathy and breadth of view; of Chelsea Atwood, equally successful, raucous and humorously contentious, the best of good fellows and the most generous to those in distress. We think of the lawyer, Minot Fowler, who united deep learning in jurisprudence with an intense love for classical scholarship; of the other lawyer, Deac Merrill, . the most loved of and by us all, always a joy to a great circle of friends and one to whom all acquaintances were friends, the final victim of a needless tragedy. These and many others we remember with respect and above all warm affection. And we have a right to conclude that the educational institution which, in the nineties, did its share in the development of men like these has an assured place among the beneficent institutions of the land.

Such is the story of 1900. The fifty years which have elapsed since its graduation, except for the period at its beginning which now seems to us by contrast one of heavenly calm, have been years of stress and strain, of crisis and heartbreak. All institutions, Dartmouth among them, have been subjected to new and unheard of problems, to hesitations, doubts, sometimes failures, but largely to great and laudable progress. For that period the College has enjoyed the leadership of another great president in Ernest Martin Hopkins who, but for a curious twist of fate, would be one of our own. Through his exertions the College made progress by leaps and bounds. Now, with world conditions what they are, it is confronted by a crisis more serious than ever before. But the whole history of the College is a repeated story of crises and crises eventually met. We do not ask, President Dickey, that you and your associates should solve all the difficulties of the College, because a college without problems is a moribund institution; we do not demand that in your efficiency all your perplexities should disappear, because a college president without perplexities must be a person of intolerable smugness, but we do expect, nay more we believe with implicit confidence, that under your leadership Dartmouth shall so meet her problems with efficiency and good sense that her honored position among the institutions of the land will remain unscathed.

But in doing this one prime principle must remain intact. Many types of educational enterprises are required in our varied system, but to us the core of them all is the privately endowed, nonsectarian college of liberal arts. Whatever change may be necessary in its methods, its purpose must continue untouched—a purpose which has been defined by President Hopkins in the words of the Biblical proverb of old, "With all thy getting, get understanding." That indeed is the aim of the College, for to men of understanding, by the grace of God wisdom may be added, but to the man of no understanding even the grace of God is powerless to impart wisdom by any miracle whatsoever. And wisdom is a commodity which in these days we cannot well do without.

We of 1900 do not come before you as some of our predecessors have done with the cry of the athlete of old as he faced the emperor in the gladiatorial combats of Rome; a cry repeated by the doleful American poet in his class reunion at Bowdoin many years ago—morituri salutamus. Rather we look to the future with the confidence of youth—our swan song of Dartmouth is that which we have voiced so often in the past and which countless generations of men to come will continue to voice—esto perpetua.

PROFESSOR LEON B. RICHARDSON about to deliver the 50-Year Address for the Class of 1900.

REUNION FIXTURES, demonstrated above by 1940, were informal talkfests and that cooling amber ale

CLASS SECRETARY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleBaccalaureate Address

July 1950 By THE HON. GEORGE F. KENNAN '50h -

Article

ArticleThe 181st Commencement

July 1950 -

Class Notes

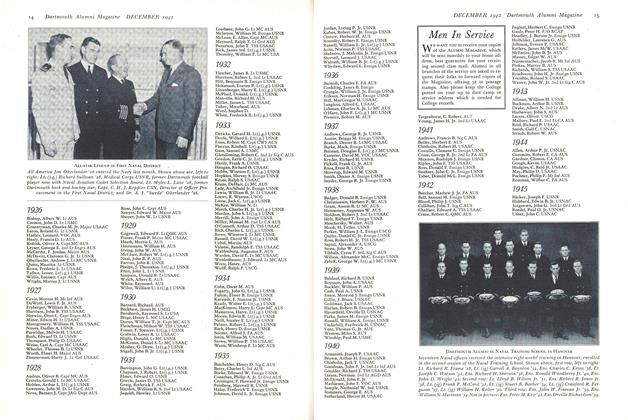

Class Notes1940's Fast and Furious 10th

July 1950 By JUDSON S. LYON '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910 Calls 40th "Best Yet"

July 1950 By HAROLD P. HINMAN '10 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Awards Honorary Degrees to Ten

July 1950 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936 Won't Forget Its 15th

July 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR. '36

LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

-

Article

ArticleUseless Dartmouth Information

February 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

November 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

December 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

April 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

May 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

June 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00