The Treasury Helps the Colleges through Some Federal and State Tax Deduction Policies

DARTMOUTH ALUMNI AND OTHERS seriously concerned about the future of higher education in the United States have been disturbed, at least since 1933, by the thought that increasing subsidies to state educational institutions and diminishing gifts to and income of privately endowed colleges, may result in the decline and ultimately the fall of the latter.

This movement, as it is thought, proceeds on two fronts. If the state institution needs a new library or athletic field, the W.P.A. builds it, or the legislature appropriates for it. In either event, we the people, whether State College alumni or not, pay for it. For these and many other reasons, taxes are high.

The corollary is that the wealthy prospective donor to Dartmouth reflects that, through taxes, he is' already subsidizing charity and education pretty heavily; that his remaining income and estate is much less than it used to be; and hence that he had better forego the pleasure of contributing a million to meet a pressing need at Dartmouth. He may also reflect, as Treasurer Halsey Edgerton does, that interest rates are low, and hence that his income available for benefactions has diminished. Certainly Dartmouth's rate of interest on endowments has declined; but the State College is not much affected by this factor for it does not depend on endowment. Taxes have not declined, and on that steady flow of income the State institution depends.

The picture is not very encouraging to a Dartmouth or a Harvard or a Stanford alumnus. We should like to feel that the position of the College in the next quarter century will improve as much as it did in the past 25 years. Those of us who came from Illinois look forward with no special satisfaction to sending our sons either to the University of Illinois or the University of New Hampshire, excellent as those flourishing universities are. We feel, and not wholly sentimentally, that Dartmouth gave us and would give our sons a series of values not so readily acquired elsewhere. We will do what we can, through the Alumni Fund and through patient solicitation of others, to provide the College with the funds it needs, not only to go on, but to build itself into a stronger institution, better able to meet the very complex demands of the times. We would be encouraged to know that our contributions and our quest are not in a hopeless cause.

Are we really bucking the government in this case? Has the federal government pretty successfully dammed the flow of bequests to privately endowed colleges and universities? What is there to be said on the purely fiscal side?

The fact is that the federal government not only encourages gifts to privately endowed colleges and charities. It actually pays a good part of them, and a particularly large share of the larger gifts.

The federal Treasury, as is generally known, has become the partner of every individual earning a little above the subsistence level, as well as of every business. The Treasury's share varies, of course, with the amount of income received, starting at a minimum of 4.4 per cent and finally reaching about 79 per cent. For present purposes, however, another consideration is much more vital. Of all net income over and above $20,000, approximately, the Treasury's share is over 25 per cent; and of all net income over $52,000, approximately, the Treasury's share is over 50 per cent.

INCOME TAX DEDUCTION

The Treasury has a standing arrangement with its individual partners, however, that it will contribute its share of gifts to educational institutions, religious or charitable organizations, chosen by theindividual partner alone, up to a maximum of 15 per cent of the net income. The effect of this arrangement is, of course, that if the individual's income is over $20,000 (before paying the Treasury its share), the Treasury will in fact contribute 25 per cent of any gift made to Dartmouth, or Harvard, or the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, or to Christ Church. If the indidividual's income is over $52,000, the Treasury will pay half of the gift; if it is over $lOO,OOO, the Treasury will pay more than half, about 68 per cent of the gift.

In other words, while the federal government does not directly subsidize the privately endowed colleges, it does markedly encourage citizens to give to them, by actually paying a good-sized share of the gift. In the case of the individual with the smallest taxable income, the federal Treasury is paying, in effect, 4.4 per cent of any educational or charitable gift he makes. The Treasury pays about one-eighth of any such gift made by a man with a net income of $lO,OOO. The technically minded can easily compute the amount in any other case by finding the top combined rate, normal tax and surtax, applicable to the particular individual's income. For contributions are deducted in effect from the uppermost bracket of the individual's net income, and the per cent the Treasury loses in tax (or the part it pays of the gift) is the highest per cent applicable to the individual's income.

This is only a part of the story, however. If the individuals' state also has an income tax—and two-thirds of the states do—there is a saving in state income taxes to be added to the saving in federal income tax. For example, in New York, the State takes 8 per cent of net incomes over $9,000. Thus, the 35 per cent governmental contribution becomes 33 per cent and the 50 per cent becomes 58 per cent. In the latter case, then, of every $ 1 which the individual gives Dartmouth, he is actually out of pocket 42 cents. The state and federal governments are giving the College more than he is. To a considerable degree, he has a free choice of deciding whether he prefers the Government or the College to use the money.

How many of us would sign up to give the College $lOO, to meet the condition imposed by some philanthropist that he would double whatever we gave? We would at least regard the philanthropist as having made a generous proposition. That proposition is the one made here, to men with incomes of $52,000 or over.

LAWS ENCOURAGE GIFTS DURING LIFE

The tax laws are framed to encourage gifts during life, rather than bequests at death. To be sure, a bequest to Dartmouth College is free from estate tax, and thus, as in the case of the income tax, the Government contributes a good share of it. However, the bequest has no effect in reducing the income tax of the decedent or of his estate. On the other hand, the gift during life is not only free from the federal gift tax, but is deductible in computing the income tax (up to the 15 per cent limit). The donor thereby reaps in effect a double advantage. Again, some states limit the deduction of bequests to those made to local institutions; and for this reason also, a gift during life is preferable. The Dartmouth alumnus residing in Illinois who plans to add to the College endowment should exercise his bounty during his life, thereby reducing his federal income taxes, and ultimately his state inheritance taxes. The latter may otherwise be a sizable sum, since a bequest outside the family suffers the highest rate.

The estate tax and gift tax combined, however, do offer a very real incentive to educational and charitable gifts during life. As matters stand now, a citizen cannot transfer to another person capital funds or income in substantial amounts (above the respective exemptions) without the payment of a tax. If he has a considerable estate, therefore, he cannot hope to transfer it intact to his wife or his children. If his net estate will be f x,000,000, he cannot hope to transmit at death to his beneficiaries more than about $BOO,OOO. Gifts and bequests to Dartmouth are wholly exempt from tax, and serve to reduce the taxable estate. If the man who is worth net $1,000,000, and who has an income of $lOO,OOO, contributes $15,000 during his life to the College, he is actually parting personally with about $5,000 income which he could otherwise keep; the Treasury is contributing about $lO,OOO. Moreover, if he retained the $5,000 until he died, the Treasury would then take 29 per cent more of it through the estate tax. Hence the $15,000 gift to Dartmouth out of income costs this man and his heirs net about $3,550; and less still if the state of his residence has ail income tax and inheritance tax. He is giving the College about $3,550; the United States Treasury more than trebles his gift.

To summarize, the tax laws are so drawn as to encourage regular, annual gifts of amounts not exceeding 15 per cent of the individual's net income. The present laws operate to discourage gifts to educational institutions or charities, subject to an annuity paid on the gift. It appears that the present value of such a gift will be free from the gift tax, but the full value of the property might be included in the estate as a form of transfer intended to take effect in possession or enjoyment at or after death. If the donor wishes to preserve his income, he would be wiser to make an outright gift to the charity of his choice, reserving sufficient funds to purchase a life annuity from an insurance company for himself.

We may end, as we started, with reflections upon the likelihood of further great benefactions to the College. Probably they are not very likely. Congress has strongly encouraged inter vivos gifts and gifts in trust by much lighter effective rates of taxation than those applicable to large estates. The division of great fortunes during life among members of the family and others is a daily occurrence. Income taxes are already high, and bound to go higher. The possibility of the accumulation of large capital funds, to be contributed at death to educational and charitable institutions or to be passed on to children, is much less than it used to be. The College's reliance, therefore, must be upon a steady flow of smaller gifts from many donors. Fortunately the policy of the Alumni Fund in this respect is exactly the policy fostered by the federal and the state governments in the income, gift, and estate tax laws. It remains for Dartmouth alumni and friends to understand and then to act upon the policy of directing gifts during life to the College to an even greater extent than has been true in the past.

FORMER UNDER SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

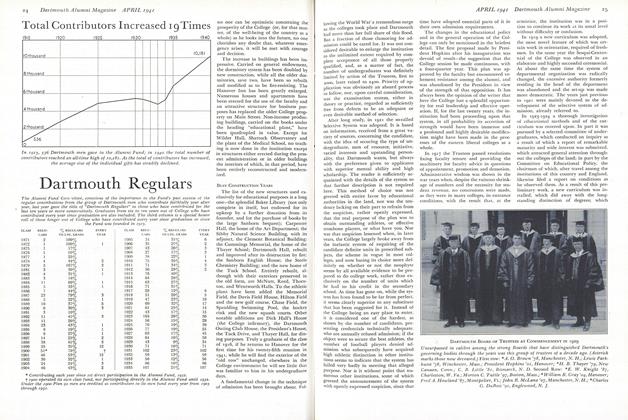

FeatureReport of Twenty-Sixth Alumni Fund

April 1941 By SUMNER B. EMERSON '17 -

Feature

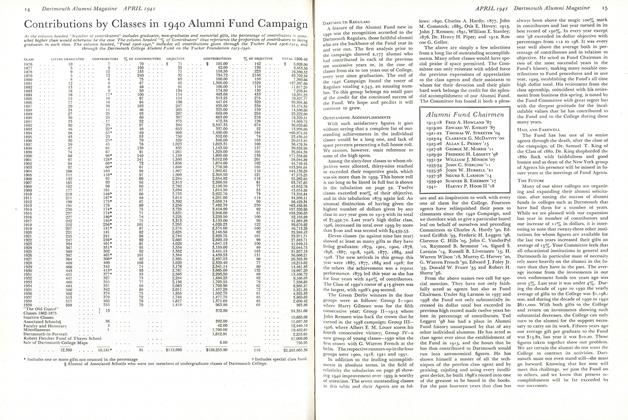

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1940 Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1941 By F. H. Munkelt '08 (Thayer '09) -

Feature

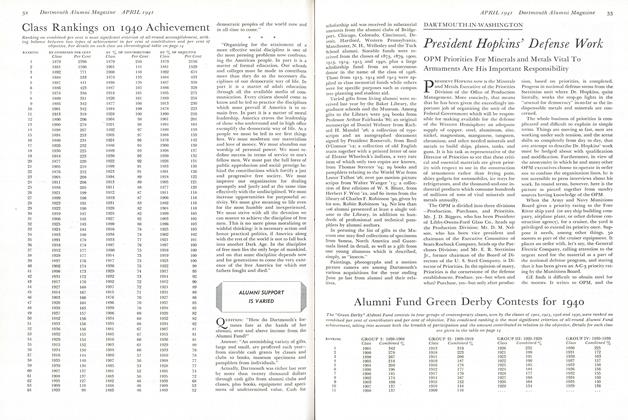

FeatureClass Rankings on 1940 Achievement

April 1941 -

Feature

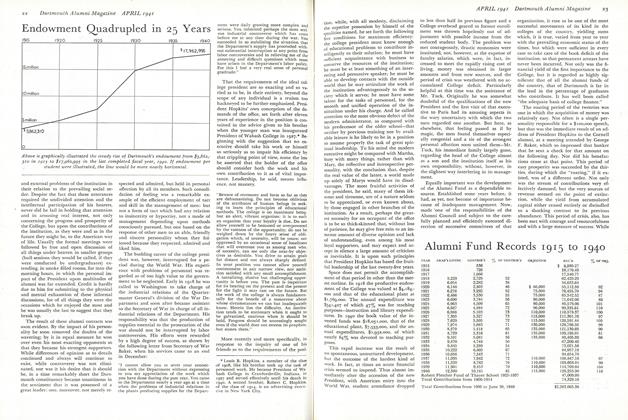

FeatureDartmouth Regulars

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Records 1915 to 1940

April 1941