"College Overtones In Time of War" Is Subject of Convocation Remarks to Student Body and Faculty

The complete text follows of President Hopkins' address in WebsterHall, crowded to capacity, on September 14.

MEN OF THE COLLEGE: Today once more we meet in assembly as the Dartmouth family. In olden days presidents of other colleges situated in more populous centers used to liken Dartmouth to Durham of old: "Half house of God, half castle 'gainst the Scot." It is in consideration of the College in both capacities that I wish to speak to you for a few moments today.

In an eloquent passage, descriptive of Oxford after seven centuries of periodic storm and crisis, the historian Mallet characterizes her present condition as "young in heart and ineffaceable in beauty, sharing her treasures ungrudgingly with those who seek them, her spirit with those that understand." In like condition today this college proffers to you share in her treasures and participation in her spirit, to the extent that you seek the one or develop sensitiveness of understanding to appreciate the other.

To you all, from those soon to leave these halls whom we have come to hold in respect and affection to those who are just entering them for whom we have high hopes, I extend Dartmouth's welcome.

I welcome you into the ranks of that procession of life that forming a century and three quarters ago, before even the national government was established, has marched steadily, without interruption, up to the present day, through calm and storm, through peace and war.

I welcome you into a distinguished society, associations with which may justly give you pride, and with the name of that society I greet you

MEN OF DARTMOUTH!

History repeats itself. Twenty-five years ago in this place on a like occasion, I spoke upon "The Need for Unusualness in the Work of the College." Then, as now, the undergraduate was torn between conflicting impulses as to what he should do; confusion of counsel emanated from high officials of government; and query was existent on all sides as to the ability of democracy later to recover the liberties which it was being called upon to give up. Then widespread doubt was expressed likewise that the attributes of a liberal education, as of fered in the historic colleges, would ever be restored again once the war emergency was past.

On that occasion a quarter of a century ago, I argued that it was a violation of the very principles for which the College stood that we should try to keep it usual. I allowed myself the assumption, which later proved to have been justified, that the students then entering or returning to college came with a seriousness of desire and with a determination to improve opportunities such as had been too little utilized in peaceful days before the crisis arose. I urged upon the student body acceptance of a cooperative responsibility among all units of the Dartmouth constituency to make the College unusual.

The responsibility was accepted, the cooperation was given, and eventually Dartmouth emerged from the chaos of that period stronger than ever before. The very magnitude of the difficulties to be overcome and the effort required to overcome them bred strength and imparted vigor to the whole College purpose.

Now again an almost exactly analogous situation exists. There is no reason to suppose that students will be less serious or less cooperative than then, as there is likewise no reason to suppose that officials of the College—trustees, faculty, or administration—will be less intelligent or less perspicacious.

If the philosophy of the liberal college were so lacking in flexibility and elasticity as to be endangered each time that it had to meet the hazards and difficulties of changed conditions, the liberal college would have become extinct long ago. Always, however, when necessity or want has required that for a time the usual functions of institutions of this type be foregone, men in grateful memory have treasured associations which have kept alive those ideals for which these institutions stood and in the course of time have made possible the restoration of these.

With these facts in mind let us together examine the Dartmouth of today, and particularly its personal relationships with you of the undergraduate body the youngest of many thousands of her sons in full understanding that these relationships are and must be unusual, as compared with either what has been or what will be.

Under any conditions, either of peace or war, those to whom enrollment in a college is available are beneficiaries of special privilege. Particularly is this so at the present moment. Barring unforeseen blessings of good fortune, these days of your college course immediately before you will be the last time for the duration when men will be free to seek that form of higher education which has been offered by the historic college of liberal arts. Already in the accelerated program leisurely reflection upon the circumstances of life and unhurried contemplation of the laws governing its vicissitudes, which are conventional attributes of the liberal college, are no longer possible under necessities of the present. No longer can we avail ourselves of Bagehot's prescription for the acquisition of wisdom, that it requires "much lying in the sun." The days before us must inevitably be days of compulsion and of hurried training.

MUST WAGE TOTAL WAR

As Mr. Churchill has said, "Our first duty is to survive." Increasingly it becomes clear that no survival of civilization as we have known it and no development of civilization such as has been craved by our aspirations can be conceived on any basis except that of first achieving military victory. Military victory against a foe waging total war cannot be won except'by waging total war in return. For the immediate future, increasingly cultivation of the liberal arts must make way for development of capacity in the applied arts. Perhaps another phrasing of the fact would be that amateur scholarship must temporarily give place to professional scholarship. Both from the point of view of your own personal interest and of society's future need, there rests upon you undergraduates of Dartmouth College the obligation not only to extract the last possible modicum of all educational advantage from your term in college but as well to cultivate appreciation of the needful values to a free people of liberal education, that though the light from this torch be reduced to a spark, it may speedily be blown again to brilliant flame when first military victory is won and peace is brought back to the earth.

Meanwhile, in war as in peace, the combined purpose of the College and of its students should be the enlargement of the minds and hearts and souls of men. No man who is not seeking such enlargement has any right to be in college at this time. Conversely, no man who is genuinely seeking such enlargement need feel doubt as to his right to free conscience in delaying his entrance into the armed services until specific call is made for these. Henry J. Taylor, drawing on his rich and varied experience among different peoples and in contact with different governments, has in "Time Runs Out" commented on the misfortune to which the world had fallen subject, in the critical days before the war, in the domination of what he calls "low altitude men." The philosophy of these, he said, dwarfed the minds of men and diluted all conceptions of integrity, knowledge, social organization, and God. Certainly in any circumstances high altitude men are going to be indispensable and unless the colleges can show capability in developing such men, they will be little entitled to the preferred position among the institutions of mankind they now hold.

Amongst most of us our instincts lead us towards the petty gratifications of self-in dulgence far more frequently than towards the struggle for increased stature in mind and spirit which cannot be found except in self-sacrifice and in self-forgetfulness. The Baruch committee's slogan, "Discomfort or Defeat," bears upon this matter and defines a problem of man's instinctive behavior, the significance of which would seem to be too absurd to accept if it were not everywhere so evident; namely, the extent to which man's resistance to change of habit may endanger great causes. General Currie, the distinguished Commander of the Canadian Corps in the World War and later the Principal of McGill, once said that it was his experience that the AngloSaxon would accept the hazards of death in battle far more readily and with far less complaint than he would accept monotony in rationing or confusion in billeting. We in this country, with three-fourths of all the luxuries available to the peoples of the earth, had come to value our privileges of self-indulgence as of inordinate importance. Some of us had appraised them as so consequential that rather than sacrifice them for a time, we had even been willing to risk their loss for all time. From such spring the appeasers and the defeatists when life begins to demand self-sacrifice.

MAY SAVE CIVILIZATION

In our deep concern then about the effects of the war, let us not forget how great need of concern there was, if only we had been conscious of it, in the aspects of modern society and in the tendencies of modern life. When history establishes its perspective upon our time, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that this great war with all of its varied costs will prove to have saved civilization in our time from attrition and slow extinction induced by our absorption in its purely material welfare. In many cases if those considered leaders of our intellectual and civilized life of the last few decades had been interrogated according to the old hymn query, "Must I be carried to the skies on flowery beds of ease?", the answer would have been almost inevitably "yes." Under the leadership of our politicians, our educators, and our theologians, the idea of hell has been deleted from men's minds, unpleasant conceptions like retribution for sin have been abolished, from our thinking, and difficulties of any sort in the path of mankind have been held to be dire misfortune. Meanwhile, since strength in any field is impossible of cultivation except against resistance and too often we have been unwilling to undergo the hardship or to make the effort to develop resistance it was bound to be that successively year by year we should have become softer and more flabby in our thinking, as in all else, and until recently we did.

At the same time, within our colleges and outside, bitter complaint has been made that no knowledge was being given of reality. However, the minute that one tempered by the fire of experience has attempted to give knowledge in regard to realities which involved difficulties, youth has argued for disregard of them on the ground that they weren't idealistic. One of the greatest problems which higher education has faced in the recent past has been how to transmit ability to youthful minds to differentiate between the idealism of its aspirations and the realism of facts under which alone real. progress seemed possible.

In this connection, realistically, there is one point upon which the leaders o£ the United Nations are in complete agreement with the overlords of the Axis; namely, upon the importance of mental attitude towards winning victory. Hitler says, "The question of how to win back German power is not: How can we manufacture arms? Rather it is: How can we create the spirit which renders a people capable of bearing arms? When this spirit dominates a people, will-power finds a thousand ways, each of which leads to a weapon."

ADMIRAL BROWN QUOTED

On the other hand, Admiral Brown, one time Superintendent at Annapolis, speaking last week at the graduation exercises of the thousand men going out from the Naval Training School at Dartmouth, talked in the same vein, as have many of our political and military leaders. He said:

"When we attempt to evaluate the variious factors that will lead us to eventual victory, we are apt to overrate material resources, war production capacity and total population, and to lose sight of the even greater importance of the fighting qualities of the race. There can be no question that the number of planes, ships, guns, and all of the other instruments of war that we are pouring out in such vast quantities are playing and will continue to play a decisive part; but the conviction has been growing on me that we are head and shoulders above all other nations in the vast number of young people whose basic education enables them to master every technical detail of modern scientific war and who, in addition, have the will to fight and the will to win."

In armed conflict the "will to win" includes very definitely the "time is the essence" dictum as a factor of vital importance. In contrast to this need may I repeat what I have often said before, that the process by which the College has been accustomed to develop manhood has been justified rather by its eventual results, than by any promptness in accomplishing these such as is indispensable in time of crisis. The intelligence which college work should inspire has been too leisurely sought. The habits formed have not infrequently been handicaps to overcome in later days. Vacillating impulses have been tolerated in lieu of well-considered purposes; and the development of character has too often been held a question of remote moral obligation, rather than an intimate essential of any complete manhood. It is in such respects that at a time like the present we little want the College to be usual. It is in such respects that it devolves upon all of us to strain that it shall not be usual.

If the uneasy desire which every man has to do something more than is at hand to do can be brought definitely to bear at this point among us who for the moment at least represent the home guard of Dart mouth men, if our effort and our accomplishment shall be made distinctive in preparation for public service, not only for the present but for the long years of our lives which will follow the war, then indeed the College will have kept faith with those who have gone out from its halls and will have begun to make its needful contribu- tion to the necessities of the post-war world to be.

COMBINE REALISM AND IDEALISM

Today we have the experience of the past to teach us that indispensable to all else as it is that winning the war should be our first concern, even this accomplish- ment will have been in vain if mastery of the problems of the peace to follow cannot likewise be won. Herein will be demanded the backgrounds of combined knowledge and contemplative thought, of realism and idealism, which it is the function of the lib- eral college to give. God grant that from amongst you there may be those who from beginnings here in cultivation of their abil- ities, in the disinterestedness of their pur- poses, and in the humbleness of their spirits may then qualify for giving succour to stricken humanity.

In Scriptural narrative a confused and lonely girl was called upon to save her peo- ple. Of her at a moment of doubt and hesi- tancy the challenging query was made which, Men of Dartmouth, I make to each of you today: "Who knoweth whether thou art come to the kingdom for such a time as this?"

REPAIRS ON LEDYARD BRIDGE BY DARTMOUTH DETACHMENT, JULY, 1918

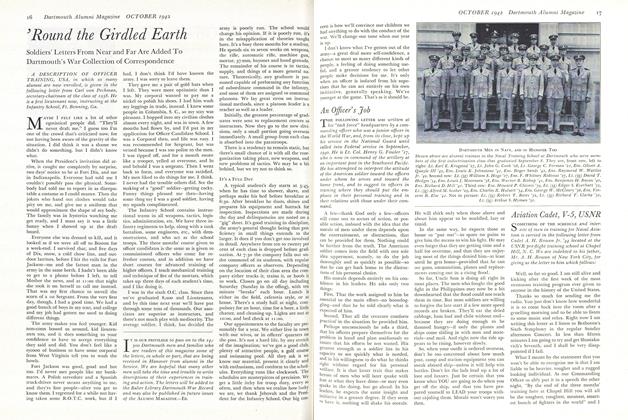

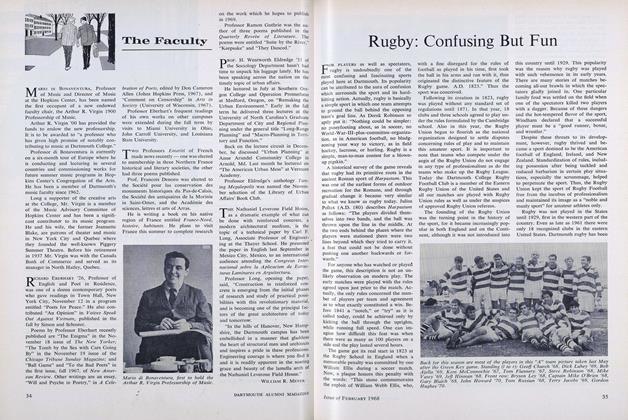

NAVAL CADETS IN TRAINING AT PENSACOLA Listening to Ensign W. E. Callahan's instructions concerning the mechanism of a U. S.Navy Seaplane are eight former students of Dartmouth College, now aviation cadets un-dergoing training to be naval aviators at the "Annapolis of the Air," Pensacola, Florida.From left to right are: Cadet W. H. Sleepeck '4l, Oak Park, III.; Cadet P. C. Thomas '39,Pittsburgh, Pa.; Ensign Callahan; Cadet J. F. Huber '4O, Northampton, Mass.; CadetF. G. Coffman '42, Webster Groves, Mo.; Cadet H. Garlick '43, Sharon, Pa.; Cadet J. W.Morton '4l, Scituate, Mass.; Cadet F. V. Davis '3B, Portland, Maine; and Cadet C. W.Marion '44, Hamilton, Ohio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

October 1942 By John French JR. '30 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Article

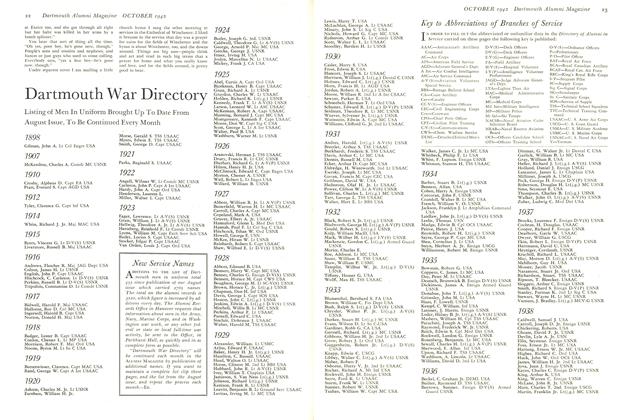

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

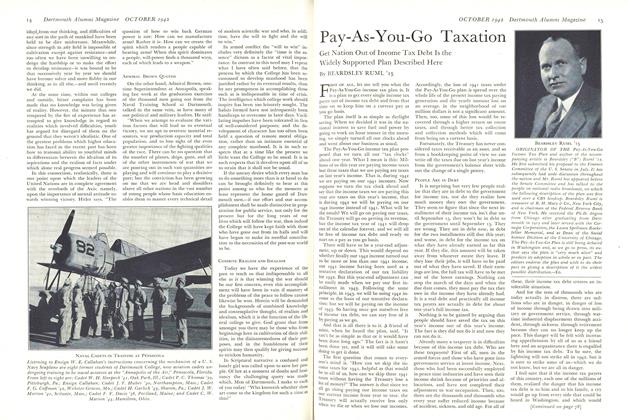

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

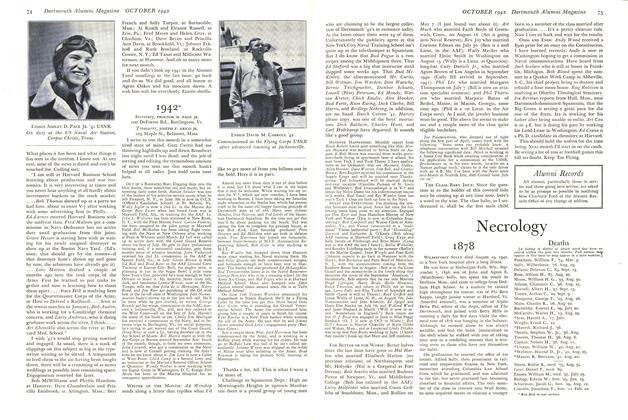

Class Notes

Class Notes1942*

October 1942 By PROCTOR H. PAGE JR., JOSEPH F. ARICO JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS RECEIVES HONORARY DEGREES

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticleFUND CLOSE TO $2 MILLION

JULY 1970 -

Article

ArticlePractice!

OCTOBER 1991 -

Article

ArticlePayback Time

July/August 2012 -

Article

ArticleMy Sister The Star

December 1980 By Frank B. Wilderson III '78 -

Article

ArticleRugby: Confusing But Fun

FEBRUARY 1968 By JOHN P. MORSE '70