AMONG SELECTED AMERICAN RECRUITS for. the King's Royal Rifles, British Infantry Regiment, are Tom Braden '40,former editor of The Dartmouth, and TedEllsworth '40, former sports editor of thestudent paper. They are well into theirtraining for commissions. Through thekindness of Tom Braden's father, and ofMr. Ralph C. Allen, president of AllenBusiness Machines Inc., abstracts fromsome of Tom's letters follow:

There is some news: One night Ted Ellsworth and I were walking in from (censored) in a soft rain and we met Captain Ritchie, our commanding officer, who told us, more or less by way of conversation, that Bolt£ and Brister and Durkee and Cox and Cutting were soon off for "overseas." He told us where they were going, and you would be right on your first guess, and he said he expected that we would be following them soon. Afterwards Bolte wrote from the battalion and said, "All is terror and delight here," and one by one that week they drifted into Bushfield to be saluted and welcomed by their old sergeants and corporals and to talk to us in our corporals' room (pretty revolutionary thing) and to go out to Newmans to tea, and down to Besnons to wander around the huge old estate I told you about which gets lovelier and lovelier each time I see it, and to review our cadre class on the square.

They laughed, of course, when Ted and I marched by and we were embarrassed and I got to thinking about how strange it was that Brister should be standing in an officer's uniform and trench coat, looking like a painting of a great general surveying the field of combat, the wind blowing back his military coat, and that I should be saluting to him, and looking upon him, in spite of myself, and because of my rigid army training, with a kind of awe and knowing that it was only Brister and that he and I knew this was baloney. And yet I mustn't let on that this was baloney, and neither must he, and pretty soon if you don't let on when a thing is baloney, it soon becomes very real and important and you don't see that it is silly any more. Well, anyhow, I got to thinking about this as we were marching past, and then the Sergeant gave "saluting to a Junior Officer, to a Junior Officer, Squad salute (Mental reaction—Halt, turn, salute for five, turn, march on) and I looked at Brister just then and he laughed and I nearly dropped my rifle, and had to reach for it, and got out of step and spoiled the whole thing. And Sergeant Crouch wanted it to be good too. So the company commander told him it was "a poor show" and I felt sorry for Sergeant Crouch, though to look at him and hear him speak to you, you would not think he was the kind of man you could ever feel very sorry for.

THREE IN ACTION

So the first five of us are off. They made a good record and they are good guys. They kept their heads for the most part and England and the army didn't spoil them. They let all the baloney of the English army slip off their shoulders for the most part and concentrated on the job they set out to do which was to learn to fight the Germans, and they did learn, better than all the English guys they were in with, and that they finished at the top of their class though they still couldn't march correctly and now without a doubt they'll get their chance to fight, and kill. I hope they all come back. I shall never forget Brister's parting remark to the Lieutenant at Bushfield who is so concerned with drill and smartness. He and Brister stood on the cement path leading to the square and a squad went by and he said, "Well, what do you think of the men?" and Brister looked at the sweating bunch of rookies marching past, toiling with the ridiculously short and fast "rifleman's pace" and in a perfectly English tone and accent, remarked, "It seems to me they might swing their arms just a bit higher."

Dear R. C.: It was no picnic we were going on. We found that out right away. Our regiment has been in Crete, in Calais, in Greece, and in Libya, one of the very few regiments which has been in all the fighting to date and which will very likely be in on all that is to come. Ted and I have talked to one of the seven men from the Kings Royal Rifles who got back alive from Calais and his description of the young Germans with the itching trigger fingers who longed for a shot and took many a shot at half trained English prisoners who lagged behind was only one of the things which brought us down to earth and gave us a realistic idea of what we were in for.

In other words, we expect, before many months, to leave England for a good many miles from here.

I can't say truthfully that we're looking forward to it as a lot of fun. I suppose that one of the first things anybody who joins any army gets over in a hurry is the idea that going off to war is a glorious adventure entitling him to the kind of fake martyrdom which you hope for when as a young kid, you picture your hero's grave with some beautiful girl shedding tears over it. If Ted and I had any of that in us, and I think most people do, the dirt and sweat and work and boredom and dullness and staleness of the army took it out right away. But it is true that the Army gets yon. We've drilled in the Bren gun, on the square, with the rifle, with the anti-tank gun, with the ack ack gun, over and over and over again, from 6 in the morning until 4 at night; we've practiced getting men between our sights over and over, and what to do with a bayonet and how to use it and how to pu'l it out and how to use ground and hills, until we take guns apart in our sleep and wake up in the night thinking somebody yelled, "Gun stops, apply immediate action."

The result is that in spite of yourself and all you've been trained for, you have a strong inclination and desire to get a real man between your sights someday and pull the trigger or get real bullets flying over your head and use the ground correctly. You get a strong desire to put what you know to some use and, in the meantime, the constant drill, the vacant conversation, the lack of anything lively and inquiring and alert to the mind and the discipline, dirt and rigid order of the British Army gets you, too, and you long for anything which will be a change and think that if you got into action, you really wouldn't care a great deal whether you got shot or not.

I think it is too bad that an organization can drill the human mind into submission almost as easily and cleanly as it can drill the human body, but it is nevertheless true. I have always wondered how it was that good men went into battle, and now I know.

I think that is the way most people are over here. The war is a pretty real and close thing. Ted and I, when we go to people's houses are very careful though we made slip-ups at firstnot to make mention or ask any questions about the whereabouts of fathers or sons or husbands in the family. Far too often the answer comes in the typically English matterof-fact tone which seems to hide and probably does, a deeper feeling "He's gone now." You get that everywhere and of course there are still air raids, some of which we've seen.

There's a lot we could complain about I suppose, though we'd have no right to since we had some idea of what we were getting into: the food is scarce and starchy and not very good and hard on the stomach, cigarettes are few and we scrape all over town to get them, the pay is about two and a half American dollars a week which keeps the British soldier from carousing (a good thing for this little island when you remember that there are six million soldiers here to carouse) and the discipline and drill of the British army is stiff.

Ted and I are pretty fascinated with the English countryside—the thatched roofs, the grazing cows and the downs, which all looks like a picture on the calendar of some mortuary firm in Dubuque, lowa, and by the age of the place, the tombstones, the initials and some date like 1720 scratched in a wall, by somebody who sat on that wall long before us.

And the people—l'll try to tell you what the boys we're with are like. It's a pretty strange business. We like the cockneys the poorer English boys. They're a great deal like us, natural, doing their best, no affectation. They have been far too much bred to their class. They don't consider it proper for them to go to tea with us or with the public school boys of England. Actually they won't sit down to eat with "blokes above us." And for the blokes above them, Ted and I have no use at all. The youngest, that is the boys who have just come from Eton and Harrow, etc., are in the stage which the maturer English people call skittishness but which Ted and I would term something else. They waltz up to you and say, "Oh my your gaiters are white, how did you do it, tell me, do you use chalk?" and on and on with a feminine and nonsensical chatter.

THE BOYS IMPROVE

And the older ones are bored. Just bored to tears. They've had their commissions (all men in England who are the age of Ted and me have had their commissions long ago) or have completed their training if they couldn't get commissions and "wish that something would happen." It is the sort of pose which people adopt when they are very proud of something (in this case an officer's uniform) and wish to brag about it without seeming to brag. The other day, an English girl talked about this type and said to us, "I do think the boys improve so after they've seen a bit of action."

Yet this same girl's father was killed when the Hermes went down. He was its captain. This morning when Ted woke up, he said, "What do you think is wrong with me, Brady? How can I improve?" I told him to stand in the corner and I would fire .303 ammunition at him. I said, "I think you need a bit of action."

Now it is my opinion and Ted's that people have reached a pretty tough stage of affairs when they regard the act of going into a hail of bullets as a necessary stage in a man's passage to maturity. I suppose it is the natural reaction of a people or rather a class because the so called "common soldiers" are not like that, who must rationalize the fact that in every generation some of their sons have been called upon to go out and die.

They accept it as a part of their existence. I would like to think that this is no skin off ray back but the English and the American people are likely to be pretty closely tied up to America and the American people during the years to come. I'd hate to have them influence us in that regard.

Of course there are a lot of things we admire about them. Their quietness, their acceptance of sacrifice, their hatred for making a show (people we know here were actually sickened by America's demonstration over the R.A.F. and the winners of the V.C. at the New York parade they shut their radios off, not being able to bear to listen to a celebration over men who merely did their duties). We like the fact there's no baloney to the English war effort. Nobody is getting out of it because of necessary occupation. The old men and the women do the necessary occupa- tions and the young men—anybody up to forty, fight. Nobody is profiteering. There is an income tax of over 100% on any profits over the amount of profits made in the year 1937. There are no cars on the roads, none parked in the streets of towns, there is no fake patriotism over the radio, no flag-waving and jangling. The war is too close and real for that. The English are quietly, bravely, determined to win.

They get a tremendous kick out of Ted and me. We found pretty early that we were expected to laugh and not take things very seriously and so we don't. They are disappointed in their idea of Americans it we do and we do get a lot of laughs.

Sometimes when I see "Ted picking up an old newspaper to put aside for future toilet paper, snuffing out a cigarette three quarters gone and putting it in his pocket to use for future smoking, washing with an atom of soap which you would throw away, or standing on the barrack square in his suspenders, bawling at a squad of rookies to move to the right in threes, left turn (an order which is so completely confusing that I doubt if I could explain it myself), I ask him if his name is Ellsworth, if he had a good job and a nice home and he says, "No, Ellsworth died just about four months ago, and I am just carrying on in his place."

So you can see, we have some laughs, we're going up to London on leave tomorrow, and Ted will buy me that drink at the Savoy. I've paid him my debt at the Mayfair.

Often and in particular when a matchless England comes to Ted and me for cigarette lights—we think of you and of Aunt M. and of all you did for us and of the times we had because of you. And we laugh about them and say we'll come back and have good times again.

I forgot to tell you—we toasted to you at the Mayfair. We'll have a toast again to you tomorrow night at the Savoy.

This morning Ted and I started on what is called a Cadre course. It is a course given to picked riflemen who seem to have the potentialities, as judged by their squad sergeants after the initial training period, of becoming non-commissioned officers. The idea of the course is to take the men through the whole drill, rifle, Bren gun and marches again, this time with an eye as to how to teach the stuff. At the end of one month those who pass the course are made lance corporals and assigned to squads.

Of course we are already lance corporals. None of the other boys in the cadre I say boys, though the average age is about thirty five are. That makes it a bit difficult, since they have to call us corporal, though our classes make it obvious that we know no more than they do. The reason for this state of affairs is that after we finished our first training, we had a wait of several weeks before the cadre course started. Cadre is pronounced as though it was spelled carder. So since there was nothing much for us to do, they put us ahead of time. This happens pretty frequently in the British army, particularly with the public school boys who are earmarked for O.C.T.U. It is not a very good thing. Other men have to work to get their stripes. They have to be good soldiers. We, and others, get them as a matter of course. It is the reason that sergeants in the British army are looked upon with more real admiration than the second lieutenants.

And so today we were back on the drill ground in squad, going through the old stuff all over again, only this time we were pretty rusty, and this time, no excuses are made for us because we are Americans. As a matter of fact, Ted and I are pretty poor at drill, the poorest of the lot. It is much easier to tell a man what to do, as we did under Ellis, than to do it yourself, as we are now doing, and this morning when Captain Bering, the commander of number two Company, stopped on the square to watch the Cadre Class drilling, we could hear him talking to other officers and saying that the squad was terrible, "looks like a bunch of recruits, particularly the two yanks." Later our new sergeant stopped the squad and yelled out in disgust, "All right Corporal Brown, take Corporal Braden out and teach him how to turn about." And so it was done, very embarrassing with a left, right, left, right, A-bout, Turn, "Check," up, Two, Three, Down, until I could do it correctly.

It is a good thing for me and for Ted to begin to get picked up on things. We have been sliding along too easily, and for example, I never did know how to do an about turn. The complicated way the British army has of turning about seemed just too stupid to bother with, and so I have been getting along up to this point by just sort of walking around in a small circle of my own, hoping that I get to the reverse position at the same time the rest of the squad does and that nobody would be watching my feet.

Well you see, shirkers are caught. It's justice.

I'm not really cut up about our drill because the drill caliber of the first five Americans, Bolt£, Brister and the others is notorious at Bushfield. They never did get to do it really smartly and yet they seemed to manage all right when they got to O.C.T.U. I think I told you they graduated at the top of the class. Two of them won first and second prizes and now have all Bushfield talking. It just seems difficult for undrilled Americans to become drilled Englishmen. And all Englishmen, in some way or another, are drilled.

DARTMOUTH WAS DIFFERENT

You can see what sort of thing is on my mind and what my life is like. I never thought before, or at, or after Dartmouth that I would have a bad time someday 'because of the

"About Turn." In the evening I sit in my bunk shooting the bull with a couple of the British boys and Ted, and making toast on a little electric toaster which we have hooked up to the lighting system in a way calculated to fool the sergeant major and which we feed with bread we steal from the cook house, and on which we spread jam that some of the mothers of the English boys managed to save coupons enough to buy and send to their sons.

I do little thinking about other than army things, and little really about that. Well maybe a little. I've noticed lately a peculiar thing that the army has done to me. I think maybe I would like to get into action.

That statement probably doesn't sound very amazing to you because I presume you assumed that I had some such idea in mind when I left. But that was pretty much the eager boy stuff, the kid off to war. There is a little of that in everyone who starts off to war, I think. A sort of starry eyed feeling that being in battle would be glamorous and great to tell the folks back home, and that going off to war is a sort of martyrdom achieved cheaply—like eight-year-old kids dreaming about breaking an arm and being visited in the hospital by the girl in the next seat at school. It is a feeling which vanishes quickly when you first hit the dirt and muck and hardness and thin brutality of the army.

But the army has something to put in its place. It has drill. They drill you at sharp shooting; they drill you at bayonet; they drill you at Bren Gun; rapid fire; aiming; how to take the sword out; how to put it in; tactics, how could you get through that pass with the least loss of life. They make you think about it; they surround you with a life that is thin and narrow and starving mentally so that even the man who has never been interested in that sort of thing—to whom it would never appeal —thinks about it. They fix it so that there is nothing else to think about.

NEW THOUGHTS OF A NEW LIFE

And soon you find out something has happened to you you discover that you are sick of the whole damned drill and that you'd like to get a real man in front of that sword or that rifle and see if you've learned anything. Partly it's that you've become interested in killing. Partly it is that army life is so thin and drab that you realize that after you have been on a ship for six months and are off in some God-forsaken hole like Libya, you really won't give much of a damn whether you are killed or not.

I'm not sure but I think that's the way armies and consequently wholesale killings are made. At least it is working out that way with me. Maybe that's the reason why men who were in action in the last war never talked about it afterwards. Maybe they couldn't understand afterwards how they got to be the way they got to be.

Last Sunday a woman by the name of Mrs. Arculus and her husband, who are U. S. citizens, took us for a drive to see the New Forest. We saw the place where Rufus the Red King was slain, and we stopped and walked through several old churches with the crumbling gravestones outside and the old gravestones as the floor of the church which is so typical here. It was a pretty fine thing for them to do, and really a pretty beautiful way to spend the afternoon. It seemed rather unreal though. For one thing of course there was nobody else on the road. Petrol (gas to you) is rationed to two and one-half gallons per month for everyone and next month a new order comes through allowing no petrol for civilian use whatsoever. You can imagine how many cars other than army trucks are on the roads.

But another thing that made the afternoon seem unreal was the whole feeling of the war over here. It seems odd and almost not just, to do anything which hasn't got something to do with the war. I am writing this letter in the library of Sir Samuel Gurney Dixon where I keep my typewriter away from the boys at camp. The old books are piled high on all the walls around me. Yet I am in uniform and just now Lady Gurney Dixon showed me her Morrison shelter in the kitchen. It is a steel table, a huge thing which can be used as a kitchen table but which has a spring underneath where a mattress could be put. I felt the thickness of the steel top and exclaimed at it and asked if it had been successful and she replied:

"Oh yes, Ann (her daughter) was buried for eight hours at Exeter and we thought she was surely gone, and yet when they finally got through to her, she was unharmed. The only thing is of course that splinters will get through the sides (like any table it is open on all sides). I know Mrs. Wilson was buried at Exeter too, and she got through all right but her baby was killed in her arms by a bomb splinter."

You hear that sort of thing all the time. "Oh yes, poor boy, he's gone now, though." People's sons and cousins and nephews, and fiances or just guys who used to come calling. Everybody says, "yes a fine boy—he's gone now, though."

Under separate cover I am mailing a little church hymn I sang the other morning at services in the Cathedral of Winchester. I liked it because in the service that day was a prayer for rains for the fields of Winchester and the hymn is about Winchester, too, and the downs around. Things are big now—people think and act and read in such big terms that a prayer for home and what you really know and love, and for the fields around, is pretty good to hear.

SCORES AGAIN Lt. Robert F. MacLeod '3.9, U. S. MarineCorps, led a successful air attack against agroup of enemy bombers attempting toraid Guadalcanal airport in the Solomonson August 24. He brought down 8 planesaccording to a report in Time. The formerDartmouth football captain and All-America halfback has been in the servicea year and a half.

t [Mr. Guy Bolte, Chuck's father, has re-ceived a message from the Royal Riflemenstating safe arrival and carrying an A.P.O.address in Egypt. Nothing had been heardearlier in the summer with the exceptionof a cablegram July 28 from Capetown,South Africa which simply said "O.K."— ED.]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

October 1942 By John French JR. '30 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Address Opens 174th College Year

October 1942 -

Article

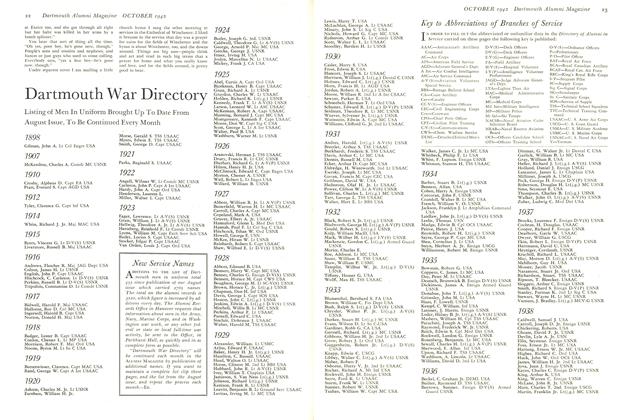

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942*

October 1942 By PROCTOR H. PAGE JR., JOSEPH F. ARICO JR.

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Manuscript Series—The First Volume

MARCH 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor"YOU CAN COUNT ME IN"

June 1933 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLiberian Correspondent

June 1939