IRWIN EDMAN, brilliant philosopher, author, and Columbia teacher, is a welcomed summer resident ofHanover whose lively thinking, writing and conversation merit a large audience. At our request Mr. Edmancontributes the following statement of his conception ofthe direction in which sweeping changes may take theliberal arts colleges such as Dartmouth, both duringand after the war. His is no casual or uninformed opinion. The editors respect his point of view and sought hiscontribution on the subject because of their belief thatthese are days in which discussion about the future ofthe College is in order. Opinions of alumni readers,agreeing or differing with our distinguished friend, willbe welcomed for publication in succeeding issues of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

Mr. Edman is a Columbia graduate., class of '77. Hisbooks on philosophy are widely known and his published works also range from poems and novels to contributions to Harpers and The New Yorker. He hastaught philosophy at Columbia since 1918.—Ed

THE EDITOR OF THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE has honored me by making me feel part of the Dartmouth family, and by asking me in that capacity to write these lines for this journal. I have no claim to being a Dartmouth alumnus except that I have spent two summers in Hanover, one of them while the College was in war session. It is true I did lecture to several Dartmouth classes, that I did spend an afternoon in the palatial quarters of the Senior Fellows with the current highly intelligent inhabitants of that citadel of learning. It is likewise true that I have made many friends among the Faculty and that I feel like a fixture of the admirable and hospitable Baker Library.

It is also true that I have at various times expressed and exchanged opinions about the liberal arts college with my Dartmouth friends. Like everyone else in American higher education the war has given me pause and cause for reflection. Like most people teaching at a city university, I have long had certain convictions about the liberal college and its future in this country. Like most city slickers I have been a little envious of the idyllic-seeming country college, an envy which has sometimes taken the form of suspicion and criticism of it.

SIDESHOW REPLACED MAIN TENT

The provocation of these remarks in these pages comes as a matter of fact from an address I gave at another college, Hamilton, this past summer. In the course of it I happened to say that colleges might, as a consequence of the war, even become educational institutions. That exaggerated crack was picked up by the New York and other papers and I have had inquiries about what I meant by it ever since. This little piece is designed to say a word of explanation.

I meant about what I seemed to mean. For various reasons, largely social and economic in character, I think American colleges, especially those not connected with universities, have not kept their eye on the ball, or, to change the metaphor, have let the sideshow take the place of the main tent. That latter metaphor incidentally comes, in this connection, from a Phi Beta Kappa address delivered many years ago by Woodrow Wilson. (It made a great impression on me when I was a freshman; it still does.) The main tent is ideas; the sideshows are the extracurricular activities, the social fol de rol, the carnivals, the special weeks, the house-parties, the social snobberies, the fraternity mumbo jumbo. With priorities now on everything it is clear that during the war these things, most of them, will go. It is my conviction that after the war many of them will remain gone.

I do not mean that I think education at college should be classes only, or that there is no point in social groups or athletics, even intercollegiate athletics, or there is no room for gaiety or fellowship. Quite the contrary. But I do feel strongly that the accent in college should be predominantly on ideas, that a college is first and foremost a center of intellectual training, a discipline of the mind. New England colleges in mid-nineteenth century were extremely serious places. Nearly everyone studying at them was preparing to be a teacher or preacher. People did not go to college because it was the thing to do, because the best families sent their sons there, because there was nothing better to do between prep school and a banking career.

WAR IS MAKING CHANGES There are serious students at New England colleges today, and some of the most interesting young minds I have encountered in a long time are students at Dartmouth now, or were last summer. There are virtues in the country college that the city college or university cannot duplicate. But there is also a residue of the "Joe College" tradition. There is a suspicion of ideas as highbrow, there is a feeling that books ought not to be taken too seriously. These things, for better or worse (I think for better), are going to be changed by the war. They are changed already. After the war I think brute economic facts are going radically to reduce the number of families who will be able to afford or will care to afford to send their sons to college as a four year diversion. Colleges will be held more responsible by the general public. Tax free institutions will have to show cause. Showing cause will have to be in the form of minds trained and responsible. More and more young men will look forward to government service. The colleges will possibly come more and more to depend, even the privately endowed ones, on government support. Alumni will, I believe, see colleges rather different in emphasis than they have been in the past.

Some of the trivia, hallowed with sentiment, will go. I do not think the loss will be severe. I think what is worth preserving about the liberal arts college will remain. But the colleges will begin to have some of the responsible seriousness of professional schools, and ideas, books, discussion of the central issues, of society, of life and of eternity will, who knows, become really fashionable among students. And I see no better place for a young man to be disciplined in these things than in the beautiful setting of the traditional New England campus, especially one blessed with a library like Baker. Those who find the prospect of a really intellectual college grim do not, I think, belong in college at all.

I rather think Committees on Admissions will increasingly believe this and act upon it. This war, it was said recently, is being played for keeps. Education is for keeps, too. Some of the frills will go, but the texture will be all the better. I see a fine future for the American college, but it is a future for minds. Heaven knows we are going to need trained ones for the future problems of democracy. Winning the war is going to be only the beginning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe American Dream: Growth of a Nation

November 1942 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Article

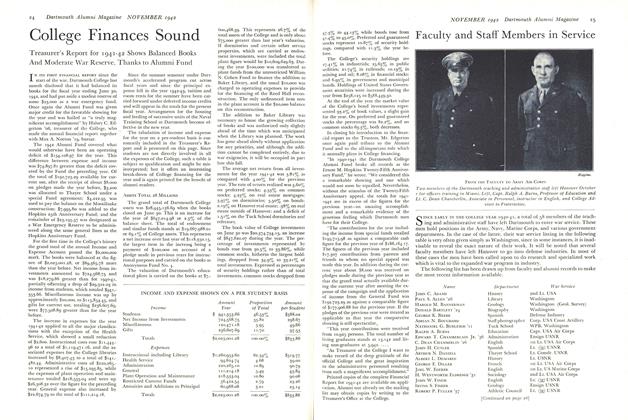

ArticleCollege Finances Sound

November 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

November 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

November 1942 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR. -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1942 By ELMER STEVENS JR. '43. -

Sports

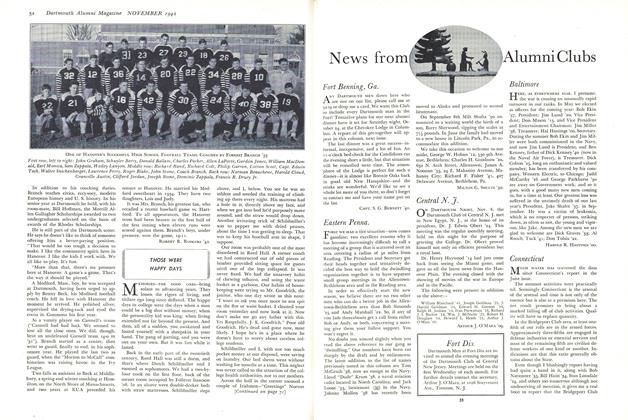

SportsTHOSE WERE HAPPY DAYS

November 1942 By Jack Childs '09

Article

-

Article

ArticleREGISTRATION FIGURES

November 1917 -

Article

ArticleNew Alumni Council Members

November 1957 -

Article

ArticleIvy Director

January 1974 -

Article

ArticleWhat Makes an Alumnus?

April 1938 By JOHN D. HESS '39 -

Article

ArticleSITUATION IS PRECARIOUS

November 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

May 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36