WHAT DO WE MEAN by the American Dream? Is it Henry Thoreau "signing oil" from institutions that limited his independence? Is it Alexander Hamilton turning to and working for the adoption of a Constitution that he did not wholly agree with but which the majority had decided upon? Is it Thomas Jefferson saying to a foreign visitor who had found on the table in Jefferson's study a Federalist newspaper containing a bitter and scurrilous attack on Jefferson and who had asked Jefferson why the paper was not suppressed and the editor punished, "Put that paper in your pocket, Baron, and should you hear the reality of our liberty, the freedom of the press questioned, show them this paper and tell them where you found it?" Is it the great infaring of the people at Jackson's Inauguration? Is it the men of Western America building their American mythology out of David Crockett and Mike Fink, a mythology whose place in the history of the American imagination people are just beginning to realize? Is it Rugged Individualists busily at work being themselves and helping themselves, while presently from Concord, Massachusetts, issued the notes of a philosophy that paradoxically part way justified them, and at the same time warned Americans of the danger of the thing they might be setting up? Is it the Utopian dreamers, those hopeful men and women of the 1840's and the 1850's, who discovered dozens of different recipes for the speedy attainment of Eden on earth: Inspirationists, Harmonists, Perfectionists, Rappites, Zoarites, Icarians, Owenites, United Societies of Believers, Social Reform Unitites, Alphadelphian Phalanxes, men and women so much at home among terms like Integrity, Harmonic Being, Progressive Being, Annihilation of Self, men and women who went and lived, some of them, in brief and hopeful communities, in bleak buildings of white clapboard or in brick Hives, Eyries, Caravanserais, while in the background talk of miraculous healing, vegetarianism, freelove, Shakerism, phrenology swirled round and round, all making for the emancipation of the human spirit?

Two OF KENNETH ROBINSON'S lec-tures in the course: "Demo-cratic Thought" are known as "TheAmerican Dream." We are greatlyindebted to him for preparing a man-uscript of the material for publica-tion, carried in these pages thismonth. Mr. Robinson says: "This ar-ticle is a condensation of a muchlonger piece of writing. Obviouslythe longer piece of work permits afuller discussion of some of thepoints made."—"Ed.

Is it William Lloyd Garrison declaring "I will be as harsh as truth and uncompromising as justice?" Is it Walt Whitman's mechanic, his red-shirted fireman, his canal boy, his Yankee peddler, his bookkeeper at his desk in the counting house, his fisherman fishing for pickerel through the ice, his trapper dressed in skins, his runaway slave who comes to his house and stops outside:

Through the swung half-door of thekitchen I saw him limpsy and weak,And went where he sat on a log and led

him in and assured him? Is it the long weaving of Western humor, that so-American thing, with its expansiveness, its irreverence for the stately, the authoritative, the official, and its drawling understatement?

Is it torchlight processions or day-long political rallies in the Illinois country, with the speaker's stand wrapped in bunting, with flags flying everywhere and bands playing, and signs that read WESTWARD THE STAR OF EMPIRE TAKES ITS WAY; THE GIRLS LINK ON TO LINCOLN, THEIR MOTHERS WERE FOR CLAY? Is it ink-smeared newspapers screaming with opinion, with one editor calling another a Pusilanimous Blathers kite? Is it looms and spindles in Lowell and Lawrence and Fall River, with the millgirls of Lowell putting out a magazine called The Lowell Offering? Is it the slow displacement of the Yankee girls who worked in those mills and the slow displacement of the Yankee men by people of other nationalities and is it those nationalities becoming something called American?

Is it the Land-Grant colleges? Is it Col. Robert Ingersoll echoing Thomas Paine? Is it Grangers and Populists? Is it William Jennings Bryan standing up in a convention at Chicago? Is it Theodore Roosevelt calling his Bull Moose convention in 1912? Is it men and women of the Dust Bowl? Is it a girl in a movie theater, sitting, tranced, dreaming of Hollywood? Is it an American boy launching a paper glider? Is it an old man, dying, looking back on the American past?

Are any of these the American Dream? Each is a figment of it, a part of it. The American Dream is a poetic phrase for an idea that the founders of this republic had and that has been put to the test ever since by successive generations of Americans, an idea that we have allowed ourselves to lose sight of from time to time, that we have allowed to lapse into the commonplace, the familiar, and that from time to time we have seen shining forth again with redoubled luster. A romantic, a poetic name to give to an experiment in government and an experiment in living? But has any experiment been more romantic or more poetic?

The phrase The American Dream has been given its greatest currency in recent years by James Truslow Adams, the historian. Writing in 1931, in the concluding chapter of his book The Epic of America he sums up certain traits of the American character and its contribution to civilization. In the realm of thought, he points out, we have been practical and adaptive rather than original and theoretical. He mentions our contributions to science, the lead we have taken in many humanitarian movements, the excellence of our recent work in literature and the drama. But, he goes on to say, "Many of these things are not new, and if they were all the contributions which America had had to make, she would have meant only a place for more people, a spawning ground for more millions of the human species." And later, "If, as I have said, the things already listed were all we had to contribute, America would have made no distinctive and unique gift to mankind. But there has also been the American dream, that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement."

Elsewhere in the same book Mr. Adams has defined the same thing in different words, and extended his definition somewhat: "The American dream—the belief in the value of the common man, and the hope of opening every avenue of opportunity to him—was not a logical concept of thought. Like every great thought that has stirred and advanced humanity, it was a religious emotion, a great act of faith, a courageous leap into the dark unknown."

Certain American writers of the Nineteenth Century may be regarded as particular prophets, seers, and interpreters of the American dream. Indeed one of them, Emerson, used almost the identical phrase in a conversation with some English friends.* "My friends asked," he writes in EnglishTraits, "whether there were any American? —any with an American idea—any theory of the right future of that country? Thus challenged I bethought myself neither of Caucuses nor Congress, neither of presidents nor of cabinet ministers, nor of such as would make of America another Europe— I said, 'Certainly, yes—but those who hold it are fanatics of a dream which I should hardly care to relate to your English ears, to which it might be only ridiculous,—and yet it is the only true.' "

What Emerson then goes on to expound to his English friends is his familiar principle (which he shared, of course, with Thoreau) of as little government as possible.

Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman lived in a sense at the center of the dream, at a time when optimism concerning it was at its peak. They had the strongest faith in the individual man's capacity to rise to the experiment, and at the same time they saw clearly enough the dangers that beset the enterprise. From their writings, making allowances for some individual differences of opinion, it is possible to get a kind of composite view of its special features.

To begin with they saw a supernatural, divine, or transcendental sanction for the idea of the democratic individual on which the dream was so largely founded. Belief in the potential integrity and worth of the individual, in his inborn right to be free, is basic to all their thinking, and that integrity and worth rests on mystery. When Emerson wrote in his Boston Hymn "God said, I am tired of kings, I suffer them no more," he was using no mere poetic convention. He came to dislike the poem but not the sentiment.

There is evident too in their idea of the American dream a mystical relationship to the Land. The part played by Nature in the philosophical systems of both Emerson and Thoreau—if the term "system" can properly be applied to what was really a considerable lack of system—is too familiar to need restatement. From the Land men drew spiritual sustenance, and at the same time the frontier, the Western land, was the proving ground, the practical laboratory for the Emersonian gospel of individualism. The land was a fact of gigantic import to the America of the time. The reality of frontier life was harsh and ugly enough but despite that fact the promise of the frontier, and the frontier settlements, was a perpetually alluring one. Emerson provided the philosophical background for the free individual of the West.

"The land," he writes "is the appointed remedy for whatever is false and fantastic in our culture. The continent we inhabit is to be physic and food for our mind as well as our body. The land with its tranquilizing, sanative influences, is to repair the errors of a scholastic and traditional education, and bring us into just relations with men and things." And again: "Luckily for us, now that steam has narrowed the Atlantic to a strait, the nervous, rocky West is intruding a new and continental element into the national mind, and we shall yet have an American genius. How much bet- ter when the whole land is a garden, and the people have grown up in the bowers of a paradise—l think we must regard the land as a commanding and increasing power on the citizen, the sanative and Americanizing influence, which promises to discover new virtues for ages to come."

Whitman, conspicuously an apostle of health al fresco, used the Open Road and the Pioneer as symbols of freedom, and saw the very core of America moving Westward. "In a few years," he proclaimed, "the dominion-heart of America will be far inland toward the West."

One of the things that occupied these writers most as they contemplated democracy was the necessity of keeping a balance between the Individual and Democratic Society, the necessity of reconciling the One and the Many, the Personal Stake and the Common Stake. Whitman chanted:

One's self I sing, a simple separate person,Yet utter the word Democratic, the word

En Masse.

Thoreau interrupted his tart strictures on society: "I have a great deal of company in my house; especially in the morning when nobody calls—Society is commonly too cheap. We meet at very short intervals, not having had time to acquire any new value for each other. We meet at meals three times a day, and give each other a new taste of that old musty cheese that we are—The value of a man is not in his skin that we should touch him—" Thoreau interrupts such meditations to announce—as Professor Matthiessen points outf—"To act collectively is according to the spirit of our institutions." And Whitman again: "For to democracy, the leveller, the unyielding principle of the average, surely joined another principle, equally unyielding, closely tracking the first, indispensable to it, opposite (as the sexes are opposite)— This second principle is individuality, the pride and centripetal isolation of a human being in himself—identity—personalism—It forms, in a sort, or is to form, the compensating balance-wheel of the successful working machinery of aggregate America."

All these men distrusted formalists and verbalists and mere man-made systems, and looked beyond them for a deeper sanction for their belief in common man, in common things.

"I ask not for the great, the remote, the romantic," says Emerson in a famous passage, "What is doing in Italy and ArabiaI embrace the common, I explore and sit at the feet of the familiar, the low—What would we really know the meaning of? The meal in the firkin; the milk in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and the gait of the body."

WHITMAN AND THE COMMON MAN

Whitman's catalogues of innumerable variations of common man, common Amer- ican humanity, in which he saw highest truths, from which some electric essence flowed out upon himself which he gave back again in turn, are too familiar to need attention here. "I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as myself."

Both Emerson and Thoreau hoped for a golden age when man could be freed from the necessity of much government. "Hence the less government we have the betterthe fewer laws and the less confided power,' says Emerson in his essay on Politics. Whitman in Democratic Vistas advises young men to interest themselves in politics, but announces that the "mission of government, henceforth, in civilized lands, is not repression alone, and not authority alonebut higher than the highest arbitrary rule, to their communities through all their grades, beginning with individuals, and ending there again, to rule themselves."

The most famous statement of the individual's relation to his government to come out of this group of writers is, of course, Thoreau's essay on Civil Disobedience. Yet no one can read that essay carefully and come away believing that when Thoreau extends the familiar Jeffersonian principle of "that government is best which governs least," to "that government is best which governs not at all," he is advocating the immediate abolition of government or even of the greater part of government. For Thoreau's statement runs: "That government is best which governs not at all; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government they will have."

And Emerson, as Frederic I. Carpenter has pointed out,J far from being an undeviating advocate of no-government, advanced in his essay The Young American the surprisingly Twentieth Century opinion that the proper function of government is "mediation between want and supply."

These men believed that government derived its powers from the individual and the aggregate of individuals and that its sole aim was to operate in the interests of those who gave it its power. And they looked forward to a day when, as men grew more and more, government could grow less and less.

The sentence "they looked forward" expresses yet another attribute of the American dream—looking toward the future. Never in American writing lias the word "future" been used with such rapturous frequency.

"We cannot look on the freedom of this country in connection with its youth," declared Emerson, "without a presentiment that here shall laws and institutions exist on some scale of proportion to the majesty of nature— It seems so easy for America to inspire and express the most expansive and humane spirit; new-born, free, healthful, strong, the land of the la- borer, of the democrat, of the philanthropist, of the believer, of the saint, she should speak for all the human race. It is the country of the Future."

And Whitman: "I submit therefore that the fruition of democracy, on aught like a grand scale, resides altogether in the future—The throes of birth are upon us." Yet the writing of these men sounds an ominous and explicit warning against threatening evils. The confidence and serenity of Emerson's presentation of the ideal often causes us to overlook his innumerable criticisms of his society and his time. Materialism, conformity, timidity are the diseases, and the cure is not easy.

'T is the day of the chattel,Web to weave and corn to grind;Things are in the saddle,And ride mankind.

Whitman states that he is not alarmed by the "intense practical energy—even the business materialism of the current age," but that he is alarmed by the lack of ideas in America, and alarmed because America has produced no Art, no Culture, worthy of her promise. In a note to DemocraticVistas he states that the two most serious flaws in American society are the lack of "moral conscientious fibre," and the barrenness of the women. But in that same piece of writing he makes a sudden and sweeping indictment of nearly every aspect of America. "The Union just issued, vie torious, from the struggle with the only foes it ever need fear (namely those within itself, the interior ones) and with unprec- edented materialistic advancement—soci- ety in these States is cankered, crude, superstitious, and rotten—Genuine belief seems to have left us. The underlying principles of the States are not honestly be- lieved in (for all this hectic glow, and these melodramatic screamings) nor is humanity itself believed in—We live in an atmosphere of hypocrisy throughout—A scornful superciliousness rules in literature —The official services of America, national, state, and municipal, in all their branches, except the judiciary, are saturated in corruption, bribery, falsehood, mal-administration, and the judiciary is tainted—ln business (this all-devouring modern word, business) the one sole object is, by any means, pecuniary gain." And he adds "I say that our New World democracy, how- ever great a success in uplifting the masses out of their sloughs, in materialistic development, products, and in a certain highly deceptive superficial popular intellectuality, is, so far, an almost complete failure in its social aspects, and in really grand religious, moral, literary, and aesthetic results."

Here the note of optimism is faint indeed. Things are in the saddle and may ride the American dream to its destruction.

These prophets, seers, and interpreters of the American dream, sympathetic to it, watching it being put to the test some half a century after its theory had been formulated, make certain assumptions, hold certain convictions, concerning it which may be summarized as follows:

1. That for the underlying idea of the democratic individual there is transcendental or supernatural sanction.

2. That there is a mystical relationship between American democracy and the American Land.

g. That the working out of the experiment requires the most delicate and constant balance and adjustment between the in-

dividual and society.

4. That the government appropriate to such a society must be a non-oppressive one and with the passage of time may grow steadily less oppressive. 5. That the fulfillment of the American

dream lies far in the future. 6. That this fulfillment is threatened, even as the optimistic prophesyings are uttered, by the forces of materialism, selfishness, greed, and unchecked individualism—of the wrong kind.

Now the word "dream," of course is capable of two interpretations. Awake, we dream of what we are going to do. Asleep, we experience certain visions from which we wake to discover that they were only visions after all and now are over. To what degree has the American dream veered from the one meaning to the other? To what extent should we talk of the American dream in the past tense?

PROGRESS INCOMPLETE

That is an easier question to answer at the present moment than it has seemed at various times in the last twelve or fifteen years, because very suddenly we are forced to realize that we do not want to talk about it in the past tense and do not propose to talk about it in the past tense. Somehow in recent years the conviction has been fastened upon us that as a nation we did pretty well up to the time of the Civil War but that since then we have been going very wrong. The picture is a familiar one and the list of causes usually assigned includes the rise of industrialism, the exhaustion of free land, the organization of big business, lapses in political morality, the influence of science—these and other well known items. Some persons hold that someone of these is responsible for all our failings, and some hold that two or three in combination are responsible, and some hold that all taken together are to blame. Most of the items are an authentic part of our history and have had consequences detrimental enough to our progress. The trouble with the picture, however, is not so much a lack of particular truth as a lack of general balance. It is easy to mistake the incompleteness of ideal progress for an absence of any progress at all. And we are too prone to pass over the quiet and less picturesque good in any period of history in our eagerness to get at the conspicuous and more picturesque evil. There are intangibles making for human betterment and human contentment, long periods of quiet living and modest aspiration and moderate achievement in the experience of most human beings that cannot be measured or arranged as statistics but that need to be thrown into the balance against the demonstrable evils when the final reckoning is made. American life has provided plenty of these secure and quiet periods—probably a greater amount than the people of any other country on earth have enjoyed during the same time.

Meanwhile we have attempted to strip man of his relationship to the supernatural or to mystery, and thereby have cut away his most important ground for belief in himself. We have been preoccupied with man the victim, victim of loveless abstractions called Forces, Laws, Trends, victim of his animal instincts and therefore the legitimate prey of the stronger and more ruthless among his fellow animals, victim of his own delusions. Perhaps the greatest delusion of modern man, however, is the delusion of thinking too meanly of himself. We have encouraged him in that. We have been specialists in his "situation," in his "plight,"—which has often been bad enough in all truth—but we have not been specialists in man himself, a necessary preliminary to getting him out of his "plight." We have not helped him to maintain confidence in his own nature. Therein is the greatest departure from the basic assumption made by Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. Emerson may be thinspun and misty in doctrine, Whitman gustily repetitious, Thoreau more than a little grudging in his admissions, but they did have positive convictions regarding man's worth. Who in America has spoken as positively of it since?

As for their other assumptions, they still hold for the American dream today and the dream goes on. The Land, it is true, ceased to be a mystic symbol with the disappearance of the frontier but we still have a consciousness of something vast at our disposal. "Resources" we are likely to call it, without specifying any particular kind of resource. Pressed, we answer "vast natural resources." The question of the balance, the adjustment between the in- dividual and society is eternal to de- mocracy; our national life moves to the rhythm of that adjustment. Government has advanced greatly upon us but Emer- son declared that the function of govern- ment might be mediation between want and supply. And except in times of crisis each advance has been met by resistance stubborn enough to prove that the old ideal persists. The threatening evils have hardly changed their essential nature. "Today amid these whirls, incredible flippancy, and blind fury of parties, infidelity, entire lack of first-class captains and leaders, added to the plentiful meanness and vulgarity of the ostensible masses—that problem, the labor question—rapidly widening every year—what prospect have we?" But wait, that is no Twentieth Century man speaking but Walt Whitman, seventy years ago. As for the future, now more than ever we look toward it for fulfillment.

There are many evidences of the persistence and vitality of the American dream through the complexities of modern times but none is so striking as the steadily increasing homage that has been paid to the figure of Abraham Lincoln. He has become the arch symbol of our democracy and of its aspiration. He touches the American dream at all points, he speaks its language, he laughs its laughter, he broods over it, he towers above it, pointing the way. To begin with he was a part of the average man's experience and comprehension. He was places like Salt Creek, Clary's Grove, and the Upper Branch. He was boys in tow linen pantaloons nursing stone bruises, girls in linsey-woolsey gowns singing "There's a Land that is Fairer than Day." He was prairie chickens and wild turkeys in Sangamon bottom land, and baskets of whiteoak splits. He was the Declaration of Independence read aloud on the Fourth of July before the eating begins. He was fishing for catfish and wrestling and getting the other fellow down and rubbing his face with smartweed. He was shirtsleeve courtrooms where everybody, judge and jury and lawyers had their coats off. He was Lyceum debates on Which has done the most for the establishment and maintenance of our republican form of government—the pen or the sword? He was "best rooms" with a what-not in the corner, a marble-topped table in the center, crayon family portraits in oval black walnut frames on the walls, and haircloth chairs that you kept slipping off when you tried to sit on them. He was the winter of the deep snow, the year it snowed steadily from December to the middle of February, and everybody's talking about it yet. He was men at a barbecue, turning the shoats and the two-year heifers in the pits while the women set out the pies and cakes. He was a man standing on the front steps of a house in Springfield while a torchlight procession came roaring down the street.

LINCOLN'S SIMPLE GREATNESS

He was all these things and then suddenly he was so much more than any of them. He was based in every man's experience and suddenly he was all common experience transfigured, given a point and a meaning and a mystery. He has been the great source of reassurance for people who have felt their faith in democracy shaken. He has appealed particularly to two kinds of Americans: poets and common men. Among the poets it was Whitman first, of course, who instinctively knew Lincoln for a great man. And most of our poets since then have paid tribute to him: Lowell and Markham and Robinson and Masters and Lindsay and Carl Sandburg, of course, and Fletcher and Stephen Benet.

But Lincoln has touched the imaginations of all classes of men; his influence has entered every walk of life. Professor Gabriel in his book The Course of American Democratic Thought has pointed out that in recent politics the name of Lincoln has been called on "to support causes as widely different as those of Calvin Coolidge and of Earl Browder." In motion pictures the mere silhouette of Lincoln's tall figure thrown on a wall is sufficient to lift that moment of the film to dignity. Barely had the last world war ended when a play about Lincoln (John Drinkwater's) filled American theatres to overflowing, and the eve of the present war found another play about Lincoln (Robert Sherwood's) doing the same thing. Dorothy Thompson wrote of seeing men weep in a New York theatre listening to Lincoln's words in that play. "I observed," she said, "that they had been hungering and thirsting for just that pathos which makes democracy and liberty vivid and dramatic." And in the most recent presidential campaign one of the contestants attempted to revive the pattern of the debates with Douglas that were held on those famous days'of 1858 in Freeport, in Galesburg, and in the other towns of Illinois.

"What is is that Americans worship," asks Professor Gabriel, "when they stand un- covered before that great silent figure? For worship they do, more sincerely many of them, than when they occupy their pews in church. They do reverence, if one may hazard an analysis of those inarticulate emotions which put an end to loud talk and to boisterous conduct, to a personification of the American faith."§ And thatmeans to a personification of the Americandream.

"IT IS A PART OF ME"

The common man has never really lost his fundamental faith in it to the extent that he has seriously contemplated exchanging the framework of American government for that of some other government in the belief that it would profit him more. Patient under adversity and largely inarticulate, he has awaited a leader and now and again pressed forward in a kind of mass assertion of his rights but always within the framework of the government, within the framework of the dream.

And now suddenly we see the American dream in a new light, the light of fierce and terrible contrast, its values heightened, its features magnified, the hope that it implies become our brightest possession. One thing about its future course is certain. The attempt to balance between the one and the many will go on as long as the dream shall last. Individualism must be preserved because it is the very groundwork of democratic belief, because it implies that a man is himself, free to think, to speak, to believe. But it must be a tempered individualism, a Responsible Individualism. That term implies a heightened awareness and consciousness of each man's part in the American whole, the sense of being a Free soul in a joint enterprise. It is that sense that must actuate our thought and our deeds for the rest of our lives. I am a part of it, is the heartbeat and rhythm of the Responsible Individual; itis a part of me.

And we are back at the future again; the American dream has always extended into the future. Is it too much to ask that the dream that we saw defined as a vision of "a land in which life shall be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement" be extended to a vision of a world "in which life shall be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement"?

KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON Has kindly put into article form, publishedin these pages this month, his lectures on"The American Dream." His courses, English 36, "American Fiction and DramaSince 1900," and English 4J, "AmericanProse," have earned wide popularityamong students over a period of years.

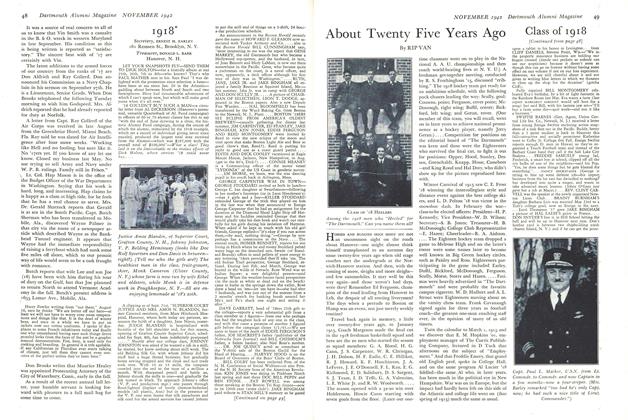

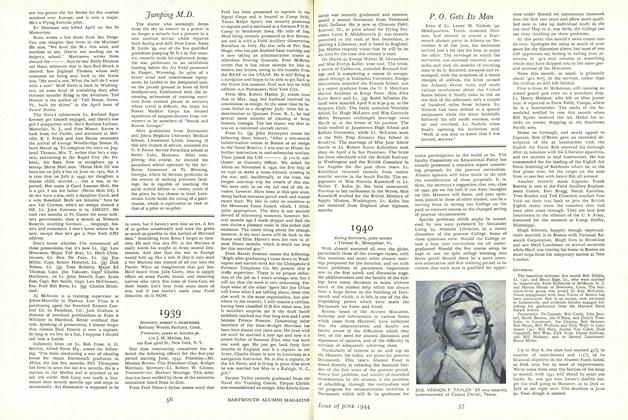

DARTMOUTH MIDSHIPMEN IN USNR TRAINING SCHOOL Alumni "aboard the U.S.S. John Jay" in New York City include, from left to right, firstrow: J. W. Curtis '42, C. L. Hopkins Jr. '42, B. E. Teichgraeber '42, M. R. Feinberg '35,D. L. Berliner '38, J. E. Griffith Jr. '4l, W. B. Provost '42, L. S. Peterson '42, A. Meyer Jr.'39. Second row: H. E. Pogue '42, J. F. Burgess Jr. '42, L. A. Highmark '39, H. A. Kaiser'35, R. L. Clarke '42, A. C. Hooker '42, J. R. Highmark '42, D. E. Provost '4l. Third row:J. Mosser '37, W. Harris '42, R. Ewing '42, G. S. Brown '42, L. H. Van Dike Jr. '38, R. A.Morrison '42, R. A. Godfrey '42, E. S. McKinlay '42, R. Hartranft Jr. '42, D. D. Scheutz'42. Absent when picture was taken: R.Geppert'42, D.D. Johnson' 37, and E.M. Skowrup.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

NOTE: I am indebted for suggestions and some illustrative material to Frederic I. Carpenter, whobriefly discusses Emerson in relation to the American Dream in his introduction to Emerson in theAmerican Writers' Series, and to Ralph H. Gabriel, who discusses Lincoln as the modern democratic symbol in an admirable chapter of his book The Course of American Democratic Thought. K. A. R.

* See F. I. Carpenter, Emerson (American Writers Series) p. xlv of Introduction.

t.F. 0. Matthiessen; American Renaissance, p. 79.

F. I. Carpenter, Emerson (American Writers Series) pp. xlvi-xlvii.

§R. H. Gabriel: The Course of American DemocraticThought, p. 413.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

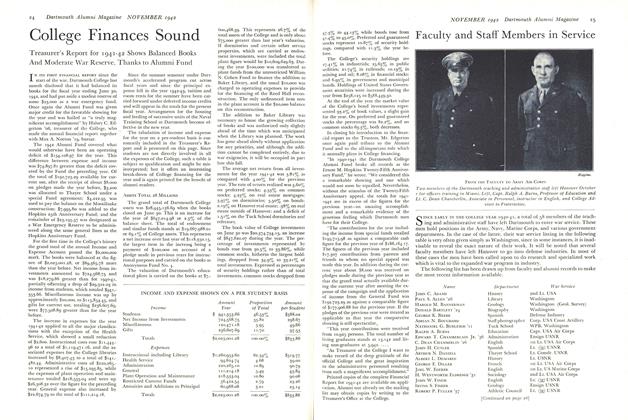

ArticleCollege Finances Sound

November 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

November 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

November 1942 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR. -

Sports

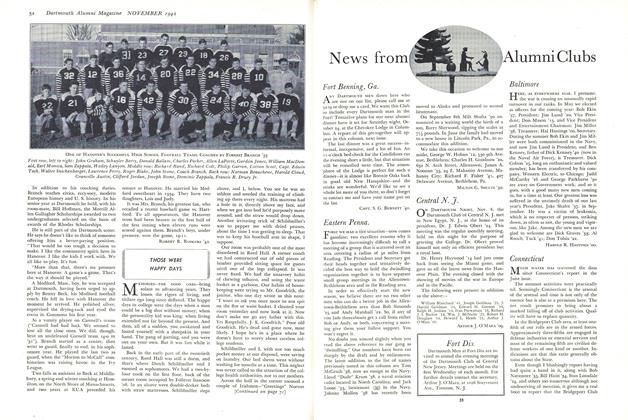

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1942 By ELMER STEVENS JR. '43. -

Sports

SportsTHOSE WERE HAPPY DAYS

November 1942 By Jack Childs '09 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934*

November 1942 By JOHN W. KNIBBS III

KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleP. O. Gets Its Man

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleParty for Bill

April 1952 -

Article

ArticleOn February 16 two representatives of the

APRIL 1963 -

Article

ArticleCan't We Get Along?

Nov/Dec 2007 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH BOOKSTORE

NOVEMBER 1962 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleREPORT FROM THE COUNCIL

FEBRUARY 1989 By Patsy Fisher-Harris '81