PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

NOT long ago I was showing an undergraduate a rare playbill that hangs framed in my office, a collector's item among playbills, a playbill of that performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre, Washington, on April 14, 1865, in the course of which John Wilkes Booth made his way down the temporarily unguarded passage leading to the stage boxes and assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

The undergraduate studied the playbill for a moment, then turned to me with a half-formed question on his lips. "Were you - ?" he began.

No, I was not," I replied severely. "Look here, young man, if I had been present at that performance even at the age of one week, an age which my parents, whether rightly or wrongly, considered altogether too young for serious theatre-going, it would still make me at least ninety years old at the present time. Do I look to you at least ninety years old at the present time?"

"Well, no," he said without conviction. "But

"There are no buts about it," I continued. "I did not bring that playbill home with me in my pocket from Ford's Theatre in 1865. I purchased it from a dealer in New York, and not so long ago - just about the time you were emerging from nursery school. Good afternoon, young man."

He left without being shown the playbill of Uncle Tom'sCabin (Boston, 1852), the playbill of Junius Brutus Booth in Richard III (Boston, 1850) or the playbill of Charlotte Cushman in Romeo and Juliet (London, 1846) that I had originally meant to show him. I did not attend those performances in person either.

Nevertheless the young man had a point. My play-going does extend over a considerable span of years - from the 1890's to the present, to be exact. And in that time I have witnessed the growing-up of the American theatre - at least as far as the creation and presentation of a distinguished native drama is concerned. I have seen it pass from a theatre of imitation and entertainment, with here and there a sporadic attempt at something deeper or more imaginative, into an adult theatre that people can really take their minds to, although sometimes their minds get pretty well battered by the experience.

Our theatre has improved in all respects but two. And those respects are big and important ones - the almost complete disappearance of the professional stage except in two or three of our largest cities - only one city really - and the price of theatre tickets. But I am content to let worthier hands than mine pen tribute to the individuals - playwrights, actors, scene designers, and directors who have been responsible for the general improvement in quality and tone. Permit me instead to be frankly nostalgic - perhaps I was present at that performance at Ford's Theatre after all - and brood for a little, not too seriously, over the passing of certain features that once seemed the very mainstays and props of drama and now virtually are no more. I do not mean "props" here in the usual theatrical sense.

Where, for instance, are Suzette, the parlor maid, and Albert, the man servant, who, as the first act curtain rose, were discovered putting the room to rights and telling the audience all about the family they were working for? Suzette with her frilly white apron and her pert black-silk-stockinged legs, and the flirtatious Albert ogling Suzette as she wielded her feather duster.

"Young Mr. Bob is drinking again. Only last night he tried to kiss me as I was helping him out of his coat in the hall."

"Nothing venture, nothing have, I always say. I shouldn't mind stealing a kiss from you myself, Suzette."

"Just you try, Mr. Fresh. You'll get a different kind of a smack than the one you expected."

Ah well, Suzettes and Alberts have pretty much disappeared from real life too - even those Suzettes that nobody ever wanted to steal a kiss from - and it may be that the reason is not entirely economic. Generations of stage domestics revealing their employers' deepest secrets to anyone who had the price of a theatre ticket perhaps created a general distrust of domestics even among those who can still afford them.

And the hoof beats off-stage! Are we never to hear them again - the cloppety-cloppety-clop of the coconut shells manipulated by the assistant property man, rising to a crescendo and then suddenly ceasing, as the messenger (who has presumably dismounted in the wings) staggers on stage, powdered with alkali dust, a bloody bandage round his head. "The Sioux are out along the Little Big Horn, and Custer is surrounded!"

Or will the coconut shells never again bring on the leading lady in riding habit? She too has left her horse in the wings but she enters flourishing her riding crop. "What a glorious gallop! Black Storm ran like a very demon this morning. Next week he'll win the Goodwood for the old Duke and Habersham Hall!" "Only if you ride him, Lady Di. No one else Can manage him like you do." And the odds are heavy that Lady Di will be climbing into a jockey's suit by the end of Act Three.

"Here she comes. Look at her. Is it any wonder the whole village loves her?" The orchestra breaks into bright rippling melody and on comes Dora Templeton, all pink and white, carrying a spray of apple blossoms and a basket covered with a snowy cloth. "Here is some good nourishing soup for you, Auntie Robb, and a loaf of home-baked bread. And I brought you these apple blossoms to remind you of the time when you, too, were young and in love."

This was not a musical show. It was straight drama. In a musical show the heroine might reasonably be expected to enter to accompanying music. But there was a time when heroines in straight drama entered to accompanying music too. And so did some of the other characters. The villain had his own creepy leit-motif that followed him about on his sinister errands. Love scenes, death scenes, were played to accompanying music, tender, lachrymose, heart-warming, heart-breaking. The atmosphere was filled with Hearts and Flowers. But accompanying music went out as Boucicault gave way to Ibsen. What tune could bring on Mrs. Alving to greet Pastor Manders come through the rain for the opening of the orphanage at Rosenvold?

"Act Four: The snow storm on the steppes. Only twentyversts to Nizhni Novgorod. Almost safe. What are thoseshapes moving through the snow? Oh God, the wolves!"

There is little doubt that winters on the stage are milder than they used to be. The snow that fell steadily through Scene Two, Act Two, of The Two Orphans, as the Countess de Linieres paused outside the Church of St. Sulpice to give money to the blind beggar girl, Louise, and failed to recognize her as her own long-lost daughter; the snow that swirled through the hallucination scene of The Bells, as Mathias the Inn-keeper re-lived his murder of the Polish-Jew traveler twenty years before; the celebrated blizzard in Way DownEast, into which Squire Bartlett drove Anna, cherished inmate of his household, when he learned about her past from the lips of Lennox Sanderson, and drew from his son, David, the ringing declaration, "Father, if Anna goes, I go with her" these have petered out into the few niggardly flakes that one was allowed to see actually falling on stage in Bus-Stop. In most plays nowadays it does not snow at all. Perhaps it is the influence of Hollywood, to whom snow is hardly a natural commodity although they can manage it if necessary. Most movies use rain to point up scenes of want, desolation, misery. But theatre folks used to be proud of their snow storms. "Prologue: [Uncle Terry] The wreck on White Horse Ledge.Rescue of the waif from the sea, introducing the latest novelty, an electric snowstorm." Yet in that last statement may perhaps be read the doom of snowstorms on stage. When they began to go electric, the zest went out of them. The flakes in the electric snowstorms were, as I remember, impossibly large. Better a few stagehands stationed in the flies with the old baskets of torn-up paper.

And the papers! What has become of the papers? The lost wills, stolen deeds, missing receipts, incriminating letters, and assorted forgeries of all kinds that used to constitute the very backbone of the drama? Where are those documents with the large red seals that someone was always trying to steal? Who dashes in any more, waving the reprieve from the death sentence that the governor has signed just before midnight? Who gathers up the pieces of the torn letter, puts them together, and discovers Lady Audley's Secret? And what about that pale-faced woman who came down the church aisle at the wedding, pointed an accusing finger at the bridegroom just as the clergyman was getting started, and cried "You cannot marry her, You are married to me already, and here is the certificate to prove it!" Apparently they do no real paper work on the modern stage. Wills are filed securely away in lawyers' safes and not hidden under loose boards in the floor where rascally nephews can sneak in and alter them. As for mortgages, does nobody have them any more? Or does everybody have them, thereby removing all qualities of the unique, the dramatic, the spectacular?

And the disguises! "Jared Fuller, disguised as Ben Clark and Tom Eastman," as the programmes used to say. The dark spectacles, the ill-fitting wigs, and the palpably false whiskers that were suddenly swept away at the moment of revealment

- "Do you recognize me now, Gideon Bloodgood?" An acute myopia afflicted nearly everyone in the drama in those days, an inability to penetrate even the most obvious crepe hair. Who, except the audience, recognized Lady Isabel in East Lynne when she came back to her former home disguised as Madame Vine, the nurse-governess, to minister at the death bed of her own child, Little Willie, whom she had deserted years before when she eloped with Sir Francis Levison? Who ever suspected that the tottering old man with white whiskers who hung about the exiles' camp in the last act of Siberia was anything but a tottering old man with white whiskers until he suddenly stood up, erect and royal, hauled off his whiskers and bade the villain "Stop, in the name of the Czar!" while the orchestra broke into the Russian national anthem?

I miss all those things - the servants dusting the furniture, the hoofbeats off-stage, the accompanying music, the snowstorms, the papers, the disguises.

I miss the adventuresses who carried small pearl-handled revolvers in their handbags and smoked depraved cigarettes in the Casino at Monte Carlo. I miss the foreign noblemen who wore broad red ribbons across their shirt-fronts. I miss the little girls who pattered downstairs in their nightgowns on Christmas Eve to interrupt the burglar at his work and reform him on the spot - "Is oo' Santa Claus?"

I miss lines like this one that I stored carefully away in my memory, hoping to get a chance to use it in real life someday - "I will not entertain an ex-convict. Go!" I miss names like the one borne by the hero of Under Two Flags who fought with such reckless bravery for the Foreign Legion in Algeria and was loved by the vivandière Cigarette - The Honourable Bertie Cecil Royalieu. How would Marlon Brando look in a name like that?

I miss scenes played "in one," down close to the footlights, to the accompaniment of thumpings and poundings behind the drop curtain as the stagehands set up for the next scene.

I miss the final curtain speeches that brought in the title of the play - "The storm has cleared, the danger is past, and straight before us, like the bright star of hope, we see the HARBOR LIGHTS."

I miss the dialect comedians. The German or "Dutch" ones (the Doppelbraus, the Buttonweisers, the rich Mr. Hogsheimers of Pittsburgh or Chicago) became unpopular after our entry into World War I; the others disappeared in the 1940's, victims of the acute rise in racial sensitivity.

And where are they gone, the old familiar farces? Farces with titles like What Happened to Jones, Why Smith LeftHome, The Wrong Mr. Wright, Brown's in Town, Mrs.Black Is Back - although the familiar essence of these was on our stage once more a few seasons ago under the title of The Matchmaker.

I miss the thrill that one got by seeing a character go by outside a window before he came on stage, especially if the play were a costume play and the character wore a caped greatcoat and a high crowned beaver hat.

And I miss the old synopses of scenes in the programmes that gave you not only the locale of the action but also the dramatic high spots to look forward to. For example, Act Three of Peck's Bad Boy: "The Picnic at Clearwater Woods, Popping the Question. Laughable Discovery of Schultz's Limburger Cheese in Peck's Pocket." The composer of that synopsis may have been a little over-confident in his choice of an adjective to modify "discovery."

Indeed with such synopses of scenes one hardly needed to see the play at all. He could construct it from the programme. "Act Three: The Football Team's Conspiracy. My God, I'm Poisoned. I Will Be Your Captain."

BUT the foregoing customs, habits, and conventions of a bygone theatre have served their turn and given way to better things. It was time for them to go. What I really miss in the theatre today is something more intangible, harder to define.

Among the travelling Negro-minstrel troupes that passed through the lost theatres of my youth was one that featured as the star number of its olio - the series of variety acts that invariably constituted the second half of the minstrel show - one Professor Homer Esterbrook rendering cornet solos on the "solid silver cornet" that had been "presented to him in person by the Shah of Persia."

Now Professor Esterbrook may or may not have come by his cornet in the manner described, but it was pleasant to think of him, clad in the light gray evening clothes with scarlet facings that set off his figure so well, playing his cornet for the Persian monarch at some twilight hour as the Shah reclined on his rugs, among his sylphs and his sherbets, in the rose-scented gardens above Teheran.

And the silver cornet, presented by the Shah of Persia, symbolizes for me a kind of rhinestone glamor, a press agent's grandiloquence, that the theatre used to have and that I miss in the theatre today.

For it was the press agent mainly who tuned the silver cornets. The press agent nowadays occupies himself with less picturesque but probably more exhausting activities such as arranging press interviews with the star of the show he is working for, making appointments with the photographers, trying to get a spread of pictures into Life magazine, or piecing together the more favorable bits from the reviews for the newspaper advertisements and the posters exhibited outside the theatre.

But the press agent of yesterday had of necessity to be an inventive person, a creative artist. That press agent who dreamed up the story about Miss Anna Held's habit of taking baths in pure dairy milk, verging on cream, undoubtedly contributed the most famous bit of creative press agentry in our theatre's history. At least it made the most resounding impact on the public's imagination and is said to have caused an immediate and impressive rise in the external consumption of milk throughout the land.

But all press agents could not be creative giants. Everywhere in the theatre lesser press agents were at work, composing their humbler fables and trying to get them printed, which was usually easy, for those were relatively credulous times.

The press agents told us how many gallons of real water were required for that scene in Shadows of a Great City in which the leading man escapes from Blackwell's Island by swimming Hell Gate; told us that the pistol carried by the hero of Across the Plains was the identical pistol that had been used by the late Jesse James to rob the Danville train; told us that Miss Eulalie Fry, ingenue of the Genevieve Driscoll Company, had been born a Siamese twin.

When it was stated in my hometown newspapers that the leading lady of a traveling repertory company about to open an engagement at the local theatre was followed from town to town by a South American multi-millionaire - a coffee millionaire, I believe - who had announced that unless she promised to marry him he would stand up in the theatre on the opening night of the engagement and kill himself with a diamond-handled stiletto, the story seemed in no way preposterous. No one really believed it, of course, although interested looks might be cast at any dark-complexioned stranger in the audience that evening, but the story fitted into and sustained our conception of the theatre as a place larger than life and more exciting than truth.

Only once according to my recollection did a press agent's efforts backfire. That was when a play came along called The Stowaway, and the publicity made much of the fact that the blowing up of the safe in Act Two was performed by "two professional burglars, reformed cracksmen." Attendance at The Stowaway was slight. The majority of the citizens preferred to remain at home that night lest the two reformed cracksmen, strolling about town during the intervals when they were not needed on the stage, should lapse suddenly into old habits.

The silver cornets have been too long silent in our theatre. Even if an actress really does get her jewels stolen, the newspapers will hardly touch the story, so suspicious have they grown of what was once the press agent's last resort when his invention flagged. Newspaper stories about current plays concern themselves largely with casting matters, opening and closing dates, and production costs. And while we are given more or less information about the off-stage doings of theatre people, the trouble is that all that we are told is likely to be true.

Last season, however, when a woman from the audience climbed up on the stage during a performance in a New York theatre and began pummeling an actor who, strictly within the framework of the play, was being unkind to his wife, there were those who saw in the incident not a triumph for art but the return of the press agent with the silver cornet set to his lips.

That was a hopeful sign. Personally I would like to hear more of the cornet music. It does little harm and adds color and joy to the whole theatrical enterprise, especially when it gets too solemn about itself. May the silver cornets blow lustily this season! But it will be necessary to travel more than twenty versts to find Nizhni Novgorod. Some time ago they changed the name of the place to Gorki.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

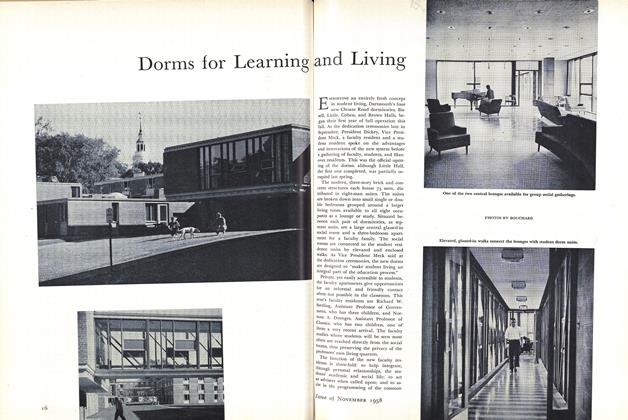

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

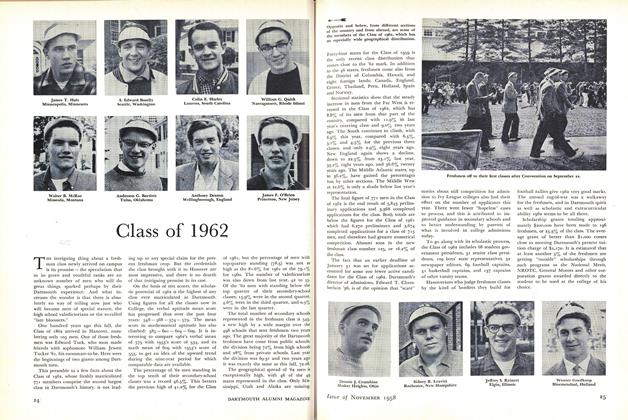

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1958 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ...