As Telescoped College Year Draws to Close, Students Find Summing Up Doubly Significant

THIS IS THE TIME when things begin to sum up. For the lower classes, final exams sum up a semester's work. For seniors, comprehensives focus two years of major study, and individual researches are boiled down into theses. In fact, everything a senior does sums up the way he's been in the habit of doing for four years. At least you can remember that as a freshman you thought you could recognize a senior by the way he lounged around campus with his jacket and his cane, and by his classroom manner, as habitual and perfected as the professor's. You wonder if you look now the way those ancients looked to you then.

Finally, not so far ahead of us now, is the time the class will be summed up in a long black-gowned procession filing into Webster for Commencement.

This is also the time when this department tries to sum up the college year from the undergraduate's point of view. For anyone in the class about to leave Dartmouth, it not only is difficult to sum up a year strangely buckled at December 7th, but it seems a little futile. It's something like predicting the outcome of an event that's just about to happen. You don't feel like working very feverishly at achieving a theoretical answer when the experimental answer will shortly be available. For the class that is leaving, this past college year, and a lot more, will be summed up very shortly in the way they act when they get outside.

REAL TEST AFTER COLLEGE

It is a commonplace observation that the real final exams come after you have strolled forth with your diploma under your arm. It's almost nauseating to repeat that bromide. But for the present graduating class, this testing process will happen so abruptly and under such pressure and to so many at once, that the feeble generalization is jolted into an appearance of unwonted life.

To put it another way, in one way or another most of us are very soon going to have to add up what we owe not only for these four years, but for what went before as well, and make what return we can. It's been pleasant. We will shortly have the opportunity of finding out whether it's been more than that.

As for most liberal college graduates, it will be not so much what we have learned as what we have learned to be that will be tested in war. Perhaps the war can show us the flaws and weaknesses of this learning. War has that capacity. The time of summing up is the time of challenging. The most rigorous challenge will be to find out if we have been fitted to make anything out of having been tested, if we can absorb and digest its lessons.

The real summing up, therefore, is yet to come. This can be nothing but a temporary rehearsal of a few of the factors that, reacting variously, stood out this year in the compounding of that mass of diversities which this department a little naively likes to lump together under the general term, the Dartmouth student.

The part of the first semester that came before the declaration of war seems farther off than last spring does. You can't help remembering last spring when you're now doing some of the same things you did then. In them, you recognize yourself as you were a year ago. But it doesn't seem as if we'll ever be again the way we were last fall. It's a funny looking montage—the puzzled, the angry, and the indifferent against a background of seething stadiums, lurid rally bonfires, cheers and band music.

We still have the puzzled, the angry, and the indifferent—those who are puzzled about what they themselves ought to do, those who are angry about what has been done by others, and those who, having settled themselves, are indifferent about the rest. But there is this fundamental difference: each particular bias is not the subject of quarrel. We all know we are thinking primarily about the same thing—the war. Last fall we were squabbling about whether or not we were fighting, and who we were fighting. But upon the declaration of war, great areas of tortured indecision were crystallized and stilled into purpose. There are still a great many questions uncomposed, but their existence tends to draw us together now rather than to estrange us from each other.

The fact is that last fall convictions were in themselves unsettling rather than composing. Feeling everything poised intolerably off balance, about to fall in some direction, we could not yet quite confidently predict; we had to step out and away from our neighbors to get our own balance. Whichever way we made up our minds, to make up our minds we had to separate ourselves from the condition of suspense in which the whole country was then hanging. Convictions then were disruptive. It wasn't until after we had all fallen into war together that convictions could promise unity.

WAR CAME AS RELIEF

So it was that when early in December we were finally introduced formally to the monster which we had been taught all during the thirties would bring the world to an end, it was a relief to us. It was immediately recognized as such. The fact that in relation to our thinking of the previous decade this was a completely incongruous reaction did not prevent it from coming to us as a relief. All our diverse individual ways of thinking were suddenly required to subscribe to one universal postulate of thinking—we were at war.

Having done so much for thinking, being at war seemed to do one more thing for us. It seemed to release us from the necessity of thinking. Convictions before war had haunted us, because there was so little to be done about them. Now, it appeared, convictions could be celebrated in action. Yet, here in Hanover, action still remained a distant possibility, postponed by college. Some left. Most of us stayed on, for a variety of reasons. Those who left made a decision. Those who have stayed have been making decisions, in the plural. Having disposed of the question one day, we had to satisfy it again the next.

SPEEDY COLLEGE ACTION HELPED

The speed with which the Administration acted to adjust the College program to the war was gratifying. There can be no doubt that it helped subdue impatience with college. All the business of a special convocation, the novelty and turmoil of the telescoped program, the provisions for seniors who might be drafted in the middle of the year, were satisfying, suiting somewhat the accelerated pulses of the students. In some ways it seemed too sudden, too drastic. But that was only at first, until it could be got accustomed to, and the recognition that the College was a little out in front was a pleasing sensation anyway. It appeared there was still some life in the old place.

All this helped us to have faith in the liberal college, and that after all, was what kept most of us here. It may be a little too much for us to take credit for having figured that out for ourselves, but it operated on us nevertheless through the advice from disinterested sources to remain in college as long as we could. The Army and the Navy told us they would ask for us when they wanted us. Gradually, the idea got across that if there were any good in this war, and any good to come of this war, college was a good place to start laying the foundations of finding out about that. People don't fight winning wars merely to preserve life and property. If they are doing that, they are losing by going to war. The French were doing that. Inevitably, they fought a losing war. But college can be a munitions factory for explosive ideas.

The story of these past months has been one of thoughts of war and acts of war, but here in Hanover, it has been mostly a story of thoughts of war and the activities of peace. Most of the events, therefore, have seemed relatively unimportant, irrelevant, so the summing up of this time has naturally had to be mostly a summary of ideas. But the only valid summary is, as I have already said, the one which is yet to come, the one which will come after graduation. In fact it will be difficult to say until then just what those ideas are.

This much, however, I would like to say, in the hope it may be true. The hope of the last time we went to war was the idea that we were ending war and making the world safe, and that hope became the threat of the post-war time. What may seem to be the threat this time we go to war—ideas for which we will be ready to fight anybody, anywhere, even here at home, and which are capable of starting wars and making the world dangerous for some time—may be the hope of this post-war era whenever it shall be.

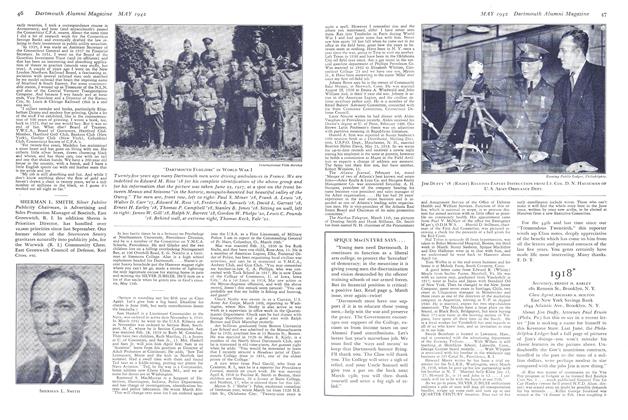

CAMPUS INTERPRETEREdward J. Rasmussen '42 of Scarsdale,N. Y., English honors student, who hasfilled the post of Undergraduate Editor forthe past two months.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Broadcasting System

May 1942 By WILLIAM J. MITCHEL JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

May 1942 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

May 1942 By James L. Farley '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWar Program Takes Hold

May 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939*

May 1942 By RICHARD S. JACKSON, BERTRAM R. MACMANNIS